The release of files for the 1990s and earlier in January previewed

Archives and the making of history

This year’s release was a poor year for anything not related to Northern Ireland and Arms decommissioning.

The flood of 6,000 odd files relating to Northern Ireland affairs seriously unbalances the release of files in other departmental areas. For instance, the files from our Embassy in the Vatican and in Italy, usually rich sources of stories relating to the Catholic Church, are quite missing.

So, too, files from North America, in particular the always interesting Irish-American material from Chicago and from Los Angeles. There are fewer historical files that were held back previously, only to be gathered up and released at this late date, which are usually also rich sources of incidents that are very striking in retrospect. However, some interesting episodes from our forgotten past were still retrieved.

A serious question

A serious question was asked in the 1930s: Shouldn’t there be a Concorde between Ireland and the Vatican?

The Free State was then, and is often today, described as a Catholic State. It was not any such thing, at least not in the sense that the government of Northern Ireland was “a Protestant state for a Protestant people”, though Northern Ireland was not actually such a thing in law either.

Did the Church always get its way in those days? Files on two court cases, one criminal, the other civil, suggest there were sometimes difficulties for the Church.

Concern

The first matter Concerns a Catholic curate in Connacht, file number (2022/24/30) dating from 1934. Fr John Fahy was well known to the police for his strong political views in favour of the Republicans. He attempted to purchase from a reservist in the Free State Army a machine gun – the type is not identified, but may well be one of those Thompson machine guns which everyone from Chicago gangsters to South American dictators – and Irish revolutionaries – was fascinated (with the same enthusiasm evinced by young Pike in Dad’s Army).

The reservist told Fr Fahy that a thing like that would cost £100 or more – though he did not, it seems, make an actual offer to obtain one. That dismayed Fr Fahy, as his militant group only had £20 in hand.

The reservist told all this to the police when questioned. Fr Fahy was detained, was charged and due to go on trial. However, he was a voluble character, and made a long statement about his position, which is on file (2022/26/31).

His bishop was very concerned at one of his priests being brought into court, and so was anxious for the matter not to develop any further. He seems to have felt that it might be quietly dropped. But the clerical obedience of Fr Fahy was in some doubt.

Fr Fahy thought this whole matter of priests appearing in court on serious charges could be resolved if a Concordat could be signed between Ireland and the Vatican. The Vatican had regained its own diplomatic status with Italy through the Lateran Treaties in 1929. This, however, was a very special case. The usual method was for a concordat between the Vatican and what were seen as “Catholic countries”. These were usually enacted with countries like Spain, France, and various South American states.

Agreements

Such agreements governed the matter of how the authorities of those states treated the Church, and how relations between the police and the clergy were arranged. There would be no appearances in court, he thought, of patriotic clergy in those countries.

But there was no concordat in Ireland. Avoiding serious scandal by a hair’s breadth, Fr Fahy came to terms with his bishop, and pleaded in such a way that the matter could effectively clear the courts, much to everyone’s relief.

Fr Fahy’s behaviour was foolish, if not foolhardy. But his thoughts about a Concordat between Dublin and the Vatican are interesting.

I suspect, reading through the file, that neither Dublin or Rome wanted any such thing. How much better it would be if priests simply stayed out of politics! In any case one gains the impression overall that the Vatican was content with having a papal nuncio in Ireland, appointed in December 1929, a person who was by rank the doyen of the diplomatic corps. They would be able to make their views known, without the unsteady and uncontrollable matter of jury trials entangling Catholic affairs.

However, even the Nuncio Pascal Robinson, a born Irishman, could face embarrassing difficulties at times. There was a dispute over, of all places, Kylemore Abbey. Due to rising debts, a sale was being forced on the nuns from Ypres. The money gained was to be used directly, the papal nuncio thought, for the purchase of more appropriate premises. Some critics, seeming close to Glenstal it appears, thought that the Ypres nuns were really not needed in Ireland – forgetting it seems that they had been granted refuge in Ireland originally after the horrors of the Great War.

Laymen

The distinguished Catholic laymen who were the financial guarantors of the original bank loan for the purchase of the abbey thought that their financial rights of repayment were to be secured first. They felt these rights were being overborne by the Nuncio. This, too, was due to go to a hearing, though in a civil court. Those involved were very anxious to avoid what would inevitably be a very great public scandal.

However, the file ends with no resolution. There was one, however, for the Abbey continued its original work, and still continues, though in a different direction today. But this matter casts a shadow over Kylemore, not discussed since. Perhaps next December a further release of files will show how the matter was settled, and how the Benedictine nuns managed to continue.

But the fact remains that great difficulties of all kinds faced the Catholic Church in the Free State years.

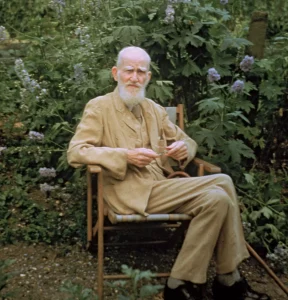

Irish Embassy in London aided author Bernard Shaw in finding an Irish maid

Irish legations abroad are well known for the care they take of Irish citizens in trouble with foreign states, or with their own documentation for travel. Many families in Ireland in recent decades have cause to thank the officers delegated abroad by Iveagh House. I have personal experience of this in matters great and small.

But from time to time these files can have a lighter, more human touch. This year, for instance, there is a file on how after an appeal from Bernard Shaw, the secretary to the Irish High Commissioner in London, John Whelan Dulanty, who had been en poste since 1930, in succession to John McNeill, came to the playwright’s aid.

Embassy

Shaw wanted the embassy’s help in engaging an Irish-born maid. This task was delegated by Dulanty to his secretary. She went about the task with great eagerness, even though she thought of Shaw as an “English gentleman” – Shaw in fact was very conscious at all times of the strong Irish connections maintained over the years by himself and his late wife Charlotte Payne-Townshend – her people were from Cork, Shaw was a Dubliner. She had died back in 1943, so Shaw now depended on his own staff a great deal.

The High Commissioner’s secretary drew up an advertisement, which was amended and then inserted in assorted Irish papers, such as The Irish Times. The answers as they came in were scrutinised and some of the applicants were interviewed by the secretary. Eventually a well referenced young lady was selected and taken into Shaw’s employment. The Shaws had always been keen on advancing women’s rights.

The writer’s household, given his age (he was 94), was a small one. The house was largely run, it seems, by his housekeeper. There was a cook too; but it was not explained to the new maid beforehand that the Shaw household was an active vegetarian (his cook later assembled a vegetarian cookbook, which was eventually published in the 1970s – some of the recipes were excellent, but perhaps only for those who like that sort of thing).

Shaw died on November 2, 1950, at his long-time home, Ayot St Lawrence down in Herts. The last items in the archive file relate, however, to a row which the maid’s mother began with the housekeeper, who had kept the maid on after Shaw’s death (rather than releasing her for new employment at once). However, among those who were familiar with the matter, including a Church of Ireland canon, the mother was a domineering personality, and he had long been anxious to get the girl out from under her thumb.

Outcome

We are left in the dark about the outcome of the row. One wonders if the maid was left a legacy, for Ireland certainly was. In Shaw’s will the National Gallery of Ireland (along with the British Museum Library and the Royal College of Dramatic Art in London), in acknowledgement of “the incalculable value to me of [those] institution[s] at the beginning of my career”, were each left a third part of the estate.

When the My Fair Lady boom began in 1956 this legacy also boomed, much to the delight of the directors of the gallery on Merrion Square. A bronze statue of Bernard Shaw, larger than life in a characteristic pose, now stands in the foyer as a token of what we can safely call national gratitude.

Foreign Affairs: ‘Keeping our eye on the Russian Eagle’

Earlier this year the news that the Russian navy was planning to hold manoeuvres off the south-west coast of Ireland caused the government concern and dismayed most Irish people. The manoeuvres were in fact planned to take place, not inside Irish territorial water, but well within our Exclusive Economic Zone – once described in these pages as “the true extent of the Irish Republic”. As a result of this controversy the Russian Navy stood down the manoeuvres.

In reality, though, this was a serious matter. A file in this year’s release contains details of Soviet activities off the Irish coast back in the 1960s and later, which makes interesting reading in the light of the recent controversy.

Three types of Soviet ships were involved: first off, merchant marine ships, carrying say, bananas from Cuba – the troubled years of the Bay of Pigs and the October 1962 face-off between the US and Soviet Union provided an unmentioned background to the file.

Controversies

Then there were fishing boats, which made the Russians participants in the ongoing and still persisting controversies about fish volumes and fishing areas in the north Atlantic.

These activities could perhaps be called normal.

But there was a third category: the activities of “Research vessels”. These too, from time to time, put into Irish ports, to replenish supplies, to seek medicines, or even hospital care. But these were within the ordinary run of things. The Irish Government at this date refused to accept official visits, in which the crew could come ashore in uniform. In Cork, for instance, there was a fear of incidents with local anti-communist groups could lead to violence – a very real possibility. The Irish intelligence service watched over these ships, and photographs of some of them are preserved in the file.

Such research vessels have long been a matter of international controversy. One of the ships in question had earlier been involved in “research” of British territories in the South Pacific, then an area where regular tests of nuclear weapons took place.

In Ireland there were no tests to spy on, but there were the beginnings of investigations for oil and gas, which would certainly have been of interest to the Russians. The file does not mention whether these intrusions were backed up by the activities of Russian agents onshore (perhaps that file has not yet been released). Certainly the Irish government and its agencies shared their concerns with their British counterparts.

These incidents were in the past. But the recent planned Russian intrusion was in the heated context of the on-going Ukrainian war.

The Irish government will also have given attention to the view of “Putin’s brain”, the philosopher and historian Alexander Dugin, who spoke recently of Russia under Putin extending the mantle of its influence over all of Europe from the Urals to “the coast of Ireland”.

‘Putin’s Rasputin’.

Coming as it did the context of the intended manoeuvres this suggested that there is serious interest among some of those ultra-nationalists around Putin in the west coast of Ireland. (Back in August, it may be recalled, Darya Dugin was killed by a bomb planted on a car in which not only she, but her father Alexander, was to have also travelled. No arrests have been made.)

The area they are interested in has since the middle of the 19th century been a significant area for the clustering of cable lines to North America and South America from places such as Valentia. Once these carried telegrams; now these same routes carry internet pulses.

During the first days of the Great War in 1914 (as related by American historian Barbara W. Tuckman in her book The Zimmerman Telegram) these cables lines were very important in altering the course of the war. Even before the shooting really began, British Naval Intelligence sent engineering ships out into the Atlantic to pick up and sever the cables connecting Germany with North America.

Messages

The Germans had then to send their coded messages by a secondary and less secure route through Portugal to Brazil and on to Mexico City and Washington DC. But tapping these lesser cable lines Naval Intelligence were able to pick up and later decode a telegram from Ambassador Zimmerman in Washington, to the Mexican government, offering them the reversal of the territories of South West US captured back in the 1840s.

The message was shared with the US government and was the immediate cause of President Wilson entering the war in April 1917, undermining the strong feeling among German-Americans and Irish-Americans that the US should not support the British Empire.

So southwest Ireland has already played a part in history. The Russians seem to be of the opinion that it will again. For it overlooks not only international communications, but also one of the largest and busiest sea trade routes in the world.

Serious thought has to be given to these hints of Alexander Dugin.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello