Powering The Nation. Images of the Shannon Scheme and Electricity in Ireland

by Sorcha O’Brien (Irish Academic Press, €29.99)

Joe Carroll

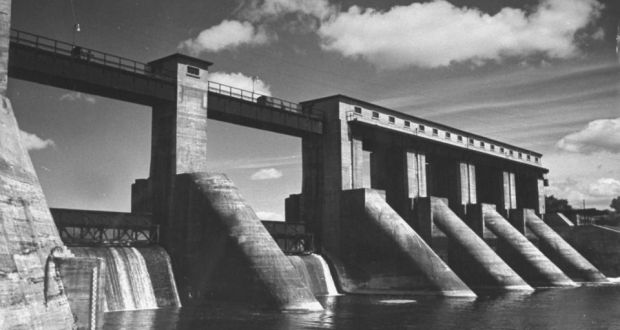

Today the Shannon hydroelectric scheme at Ardnacrusha produces about one-eighth of our electricity requirements and is mainly used at peak demand. But when it was switched on in 1929 it was designed to electrify the whole of the then Free State, and it gradually did just that.

It was an amazing achievement for a new state emerging from a war of independence and a destructive civil war. Nothing on this scale has been seen since. It is worth mentioning that it was the brain-child of an Irish engineer, Thomas McLaughlin.

An estimated 4,000 Irish workers did the donkey work of excavating and pouring concrete. Over 40 died from accidents.

The £5.5 million cost might seem puny nowadays, but it represented 20% of the national budget in 1925. Often derided by the political opposition, it was a high risk venture of the Cumann na nGaedheal government which had to rely on the German expertise of the Siemens company to get the mammoth scheme up and running until the ESB, the country’s first semi-state company, took over.

The story has been written about over the years, but Sorcha O’Brien takes the novel approach of using images to interpret its significance in a newly-independent Ireland enduring the tensions between rural traditions and the demands of modernity. Her approach through design technology and sociology makes demands on the reader grappling with the nuances of “essentialism and epochalism.”

Through images ranging over blueprints, photographs of the construction, postcards and even cigarette cards and the famous Seán Keating paintings, she explores how Siemens had to struggle at times to adapt modern engineering and electrical technology to fit into a countryside where myth and tradition were still influential forces.

But the idea of using the mighty Shannon to light up Ireland appealed to the people and the clever ESB advertising campaign encouraged the prospective clients to appreciate the symbolic as well as technical aspects of the project.

The campaign glossed over the Siemens role and the fact that most of the skilled work was carried out by German workers. But the author observes that “the political context of the building meant that the design of the power station was more influenced by the negotiations between the German contractors and the representatives of the Irish Government than is generally recognised”.

Study

Her close study of the Keating painting, Night’s Candles are Burnt Out, shows how his feelings about Ireland had evolved since the famous An Allegory in 1924 which revealed the pessimism and despair of an Ireland traumatised by the Civil War and now firmly under the control of conservative businessmen and the Church.

Five years later his Night’s Candles allegory depicts the same figures but against the background of the brute modernist Shannon Scheme. Now “the earlier noble peasants and stoic gunmen have been superseded by a new class of hero – those of the engineer and entrepreneur figures dedicated to creation and construction”.

Cynics believed that the ESB, in Soviet Union style, had commissioned Keating to do his Shannon Scheme paintings, but the author points out that this has now been refuted and that Keating carried out the work in his own time.

The dam on the Shannon

The dam on the Shannon