With Dante you do not just enter a poet’s world, but a poet’s cosmos.

Hell is defined by theologians as a place or state of punishment. Dante, Doré, and others present visions of the place, but the state of hell may be something very different to what they have so generously imagined.

Flann O’Brien more wisely suggested that hell is not so much other people, but other people constantly re-met, an inescapable mental and spiritual hell.

But in Dante one encounters at least a complete vision of the afterlife as a place. There is nothing else like it, but it needs, as Dante himself found out when he encountered Vergil, a knowledgeable guide. But there are many experts who will provide that guidance.

The first simple query many readers have is why the work is called The Divine Comedy, when there is clearly nothing merely amusing about these three long poems.

But we have to recall that in classical times drama was divided into tragedies, with so to speak unhappy endings; and comedies with happy endings. Mere laughter was provided in classical times by the Satyr plays, from which we derive our satires.

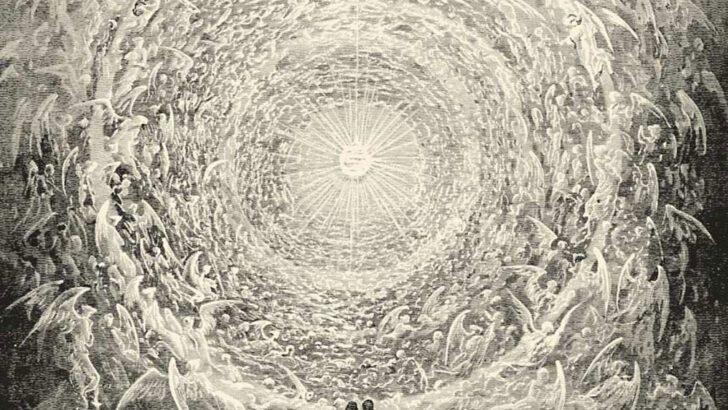

As what Dante ends with the greatest happiness possible, that of the Beatific Vision, it does indeed bring the greatest possible happiness in conclusion.

Exploration

Book review pages all too often are reduced to extended advertisements for new books. This is a shame. It is also part of a Books Editor’s task to entourage the reading of worthwhile and often overlooked books from the past.

An opportunity arises to this end for those interested in exploring Dante becoming aware of the Centre of Dante Studies in Ireland, which provides access to an understanding through not only academic ventures, but also lectures and events aimed at the general public.

This year, they have been hosting a collaborative reading of Dante’s Divine Comedy, which was directed to the Paradiso, which concluded this week.

The state of hell may be something very different to what they have so generously imagined”

Members of the public who feel they would like to learn more about the one of Europe’s major poets, his celebrated works, and the ongoing reassessments of the man, his poetry and the times he lived in, might like the make contact with the group: Centre for Dante Studies in Ireland, Department of Italian, University College Cork: www.casilac.ie/cdsi/

Aside from the general cultural interest in Dante, for Ireland he had always had special dimensions. Many Irish scholars have seen in the visionary works of our Middle Ages dealing with the afterlife, such St Patrick’s Purgatory, the visions of Tondal and others, evidence that Dante was directly inspired by Irish sources.

To others this is too broad a claim. They see those early works as having some relevance to the general intellectual climate, but that Dante deeply rooted the in culture of his own times, was initially influence by Vergil through The Aeneid in which there is a visit to the underworld, as well as, of course, Homer in The Odyssey in which Odysseus visits the underworld to met the heroes and well as his relatives.

In the Divine Comedy Dante chose Vergil as the poet’s guide because of this matter. This derives from the poet’s Fourth Eclogue, which was interpreted by Christians as predictive of the coming of Jesus.

Understandably modern scholars do not accept this view of the eclogue; but this in no way affects the fact that the medieval Europe held this idea, and that it was this idea that influenced Dante.

If all of this controversy over the very origins of Dante’s notion for his Divine Comedy is only a taste of the difficulties that face those who seriously engage with Dante’s works as whole.

Those who might like to follow Vergil and the poet into the after world would need to prepare themselves by at least some acquaintance with the Divine Comedy.

Sayers

There are naturally many versions of Dante, but since the 1950s the version by Dorothy L. Sayers in Penguin Classics has commanded wide respect.

She did not live to complete the third volume, but she brought to the task not just a mind trained in medieval literature, but the appreciation of a poet sensitive to the nuances of Dante’s vision, both theological and literary.

Like many millions already this then might be the place to begin. Those who think of her only as the author of detective novels might keep in mind that she was not merely a critic and poet in her own right, but a popular Anglo-Catholic theologian famous for her broadcasts.

Those who might like to follow Vergil and the poet into the after world would need to prepare themselves by at least some acquaintance with the divine comedy”

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Dante and Beatrice enjoy The Beatific Vision at the conclusion of the Divine

Comedy.

Dante and Beatrice enjoy The Beatific Vision at the conclusion of the Divine

Comedy.