It beggars belief that the same people who insist they want to protect vulnerable people from Covid-19 are now pushing assisted suicide, writes Niamh UíBhriain

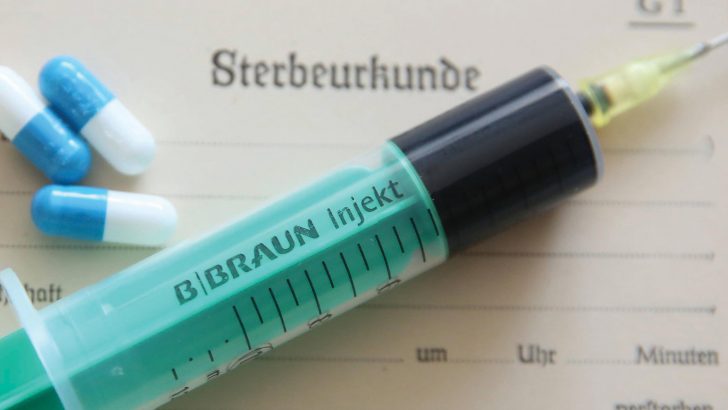

While everyone is distracted by the ongoing coronavirus crisis, Dáil deputies have moved forward a bill which would make it legal for doctors to help a person who is terminally-ill kill themselves. Gino Kenny, the People Before Profit TD who proposed the legislation, insists that he wants to assist people who are in “unbearable pain” at the end of life. But his bill doesn’t mention pain or suffering. Instead it would make it legal to help people die by suicide if they are “terminally-ill”.

A terminally-ill person is defined as “having an incurable and progressive illness which cannot be reversed by treatment, and the person is likely to die as a result of that illness or complications”. This broad definition could include Parkinson’s, heart disease, dementia and many other conditions. There is no requirement that the person be at the end of life – once a diagnosis is received assisted suicide can be requested.

Bill

The bill has been widely hailed by the media as another important step towards a more progressive Ireland where the solution to every societal problem can be met with a law that allows vulnerable people to be killed. But the same media has paid almost no attention to the most important voices in this debate: those of medical doctors and of people endangered by the bill.

Medical experts, especially those who care for people at the end of their lives, remain strongly opposed to assisted suicide. A 2019 survey by the Royal College of Physicians in London confirmed that 84% of palliative medicine physicians took this position.

The Irish Palliative Medicine Consultants’ Association (IPMCA) – experts who focus on managing and relieving pain – have written to TDs saying, with palliative care, even severe physical or psychological distress can be managed. They have warned that the “intended and inevitable unintended consequences of the proposed legislation are stark and unthinkable”.

The IPMCA say they are “opposed to any form of legislation for assisted dying, assisted suicide or euthanasia in Ireland” and that “compassion, advocacy and support are at the heart of the palliative care that is delivered across Ireland to those who are suffering as a result of advanced illness”.

The view of the leading medical experts caring for terminally-ill and elderly patients could be summarised in the words of Prof. Tony O’Brien who told the High Court in the Fleming case that doctors should not seek to “kill pain by killing patients”.

Jurisdictions

Neither has sufficient attention been paid to the experience of other countries. Only a handful of jurisdictions have legalised euthanasia or assisted suicide, but even in that limited number, what has emerged is alarming.

In Canada, the number of people availing of assisted suicide has increased five-fold in just four years since 2015. In Belgium, euthanasia cases have increased by a factor of ten since 2003, while the Netherlands has seen an almost five-fold increas in deaths since 2002. Belgium has allowed children to be euthanised since 2014. The Netherlands is headed in the same direction.

Prof. Theo Boer, who once supported the legalisation of euthanasia and who served on state review boards for the procedure, now says that the safeguards didn’t work. He estimates that one in five patients who sought euthanasia came under pressure to end their lives. Similarly, in Washington state in the US, a 2017 review found that 56% of those who died by assisted suicide felt they were a burden. What a heart-breaking statistic. No human being should ever feel a burden – it is a symptom of society’s failure to care, not of any disease afflicting the person.

Prof. Boer also points to the effect euthanasia has on ‘normalising’ suicide. The number of other suicides has increased by almost 34% in the Netherlands in the last decade, at a time when rates decreased in neighbouring countries who don’t have assisted suicide. Certainly, the message becomes mixed: when is suicide a ‘right’ and when is it something to be avoided? Assisted suicide dangerously blurs distinctions.

Pandemic

In this unprecedented year of pandemic and lockdowns, 6,751 people have died with Covid-19 in the Netherlands. In 2018, more than 6,000 people died by euthanasia, but some clinics are reporting a jump of up to 22% for 2019. It’s reasonable to expect then that the same number of people may be killed by euthanasia as with coronavirus in 2020. Why, at a time when we are shutting the country down to protect lives, would our TDs vote to make a life-ending procedure available here?

Of course, TDs are ignoring medical experts and people with disabilities because the public are not aware of how assisted suicide actually endangers vulnerable people. That’s why The Life Institute has launched a ‘Don’t Assist Suicide’ campaign to make the facts known. We need to protect lives, not encourage or assist suicide.

Niamh UíBhriain is a spokesperson for The Life Institute.