Mary, Founder of Christianity

by Chris Maunder (One World, €21.99/£18.99)

Over the recent decades the role of women in the first centuries of the Church has come under more critical examination. One result of this, arising also from developed views of the role of women in society today, has been the demand for the ordination of women.

Curiously this particular debate is not one which Chris Maunder in this book addresses. This may be explained by his background.

Chris Maunder is visiting Fellow in Theology and Religious Studies at York St John University. He is also the author of Our Lady of All Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th Century Europe, a book which aroused wide interest, Origins of the Cult of the Virgin Mary and has also edited The Oxford Handbook of Mary.

Scholar

He himself, as these titles might suggest, is “a member of the Catholic community”. But he writes here as a scholar, going back to first principles and following contemporary direction in biblical studies. Though scholarly and fully referenced his study is written in a way which presents the ordinary reader without any real difficulty.

There are naturally enough, given the nature of the records he is dealing with, many difficulties. Questions of the miracles are turned to a fuller understanding, which can be accepted or not.

He concentrates on the historical and social setting of a woman with a special destiny, as she saw it. It is startling to be told that Mary would have probably had her son at the age of 14, which was the cultural norm then. This means that when Jesus began his public ministry she was widow of 45.

Maunder sees her as playing an essential role in the organising of his ministry. This is illuminated for instance by what we are told about the marriage Feast at Cana.

Readers of the Gospels have often a sense behind what we are told, a community of women who provided shelter, food and other support thought normal for a woman in Jewish society. This is not always explicit, but one sense is for instance the arrangements made for what we now call “the last supper”.

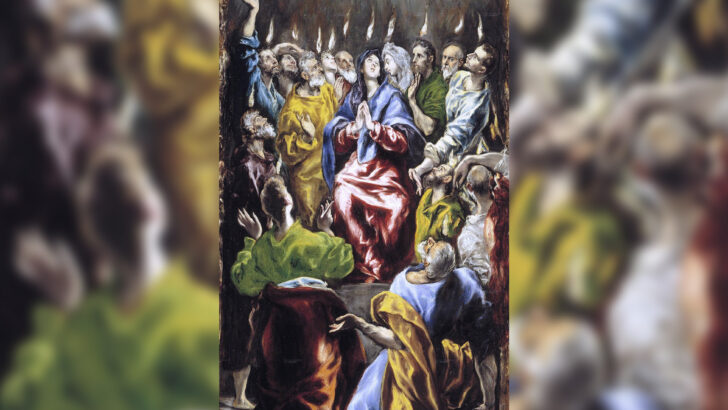

He says little here about Pentecost, but the traditional images of that event by artists show Mary seated among the Apostles, when the Holy Spirit descends on them (Acts: 1-11), though her presence is not mentioned in the text. The image however must have been a reflection of a long tradition that she was there, on an equal footing with the Apostles.

References

Maunder does not discuss this but he reviews all the references to Mary, and other women of the name in the early text. By separating them out he gives them a presence for the readers, which they would not have had otherwise. Maunder asks his readers to reflect on her role among the apostles, which he sees as one of far greater significance than many think.

However, his discussion means that he has to lose sight of the figure of May herself for extended passages of the text. It might perhaps have been better to have been more closely focused on the figure of Mary; but this would have sacrificed a great deal of his discussion of context, which is vital to the overall purpose of the book.

This will I think provide informative reading for many, bringing alive, as it does whole aspects of the New Testament which are all too often passed over in attempts to achieve a doctrinal view.

On that point, to those Catholics who take a very literal view of the gospels he quotes with relevance passages from the Vatican document The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church, prepared in 1993, prefaced by the then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. The document’s strongest critique is on fundamentalism. Those who find themselves troubled by what they hear about ‘advanced views’ should bring these observations to mind.

Chris Maunder’s book, while not without its longueurs, provides a very interesting presentation which will enlighten many readers, of interest to all who seek answers. The basic question that the book addresses is: “Who was Mary?”; the answers he proposes will interest a great many who have posed that question to themselves. He gives to the doctrinal Mary, the Mother of God, a fuller human sense of Mary, the Mother of Jesus.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello