Living Stream of Catholicism: View of the Catholic Church Through the Centuries

by Eamon Flanagan (St Pauls, £7.95)

The author sets out to highlight the living stream of Catholicism throughout the centuries and this he achieves in prose and poetry. At the outset he divides world history into a number of segments which will be familiar to students of ecclesiastical history.

The first segment from AD 30 to the conversion of Constantine is dominated by the missionary journeys of St Paul and accounts of the thousands of courageous martyrs from diverse persecutions.

With the emperor’s conversion Christianity rapidly spread across the Roman empire. Apologists and theologians availed of the opportunity to clarify and defend the teaching of the nascent Church. The author describes the next segment as the ‘Patristic Age’. It featured those who were most influential in the development of Christian doctrine, including the peerless St Augustine.

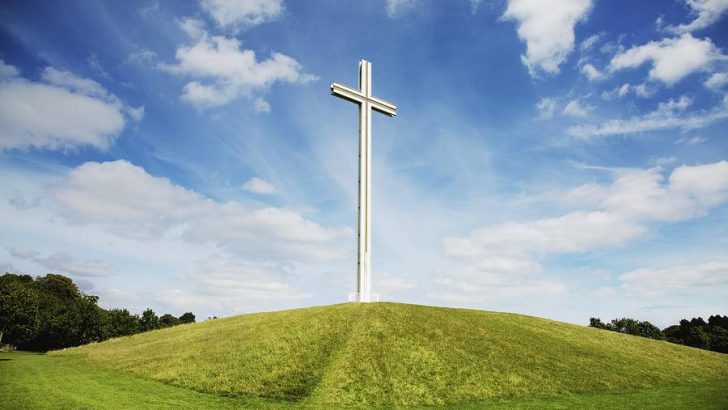

It was also the period when St Patrick conducted his successful mission to Ireland and witnessed the subsequent extraordinary missionary activity of Ss Attracta, Brigid, Columba, Columban, and Ita.

The author next focuses his attention on the much-maligned Middle Ages. The reign of Charlemagne epitomised the recovery of Europe following the collapse of the Roman empire. In concert with the Church he established political unity, stability and civilised living.

Church reform was achieved under the inspiring leadership of Pope Gregory the Great and St Catherine of Siena.

The author points to the rarely mentioned positives arising out of the Crusades. The wondrous splendour of the cathedrals of Europe dates from this period, as does some incomparable religious art.

It saw the rise of the most prestigious universities and was graced by scholars such as Sts Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure. Many religious orders with their specific charisms were founded at this time. And here, on this island, St Malachy, Archbishop of Armagh and friend of St Bernard of Clairvaux, reformed the Irish Church.

Naturally taking a positive view of the Church, there are topics on which the author is silent. The first is the Great Schism, the final break between the Greek and Latin Churches, a rupture which is now slowly resolving itself, for which many admirers of the rich ancient liturgies preserved in the East, not to mention the intrinsic doctrines of the earliest centuries of Christianity held so firmly by the Greeks, will be grateful.

He also passes over the matter of the far shorter Western schism (1378-1417), an outcome of the exile of the Popes in Avignon. But it could be said that that was a matter of worldly politics: the interference of the state in the affairs of the Church from which little good has ever come, rather than a division over religious essentials. These schisms are for many a troubling matter, but sadly cannot be ignored. Yet how miraculous it is (many would think) that the Church survived them. Later division have been less easily overcome.

The upheaval in Christianity in the 16th Century is described in terms of the Reformation and Counter Reformation. Struggles for political power again prompted religious wars. The period saw its own complement of martyrs on both sides of the great religious divide.

Humanist

Among those was the chancellor of Henry VIII, the exemplary Christian humanist Sir Thomas More. The fission in the unity of Christianity, led to Ireland’s Catholics being oppressed by the notorious Penal Laws. In due course the Irish Church recovered and the author describes Ireland’s remarkable missionary activity in the 19th Centuriy and 20th Century.

In his commentary on the Church in the modern world Flanagan ranges across the five continents. He discusses the up-dating of the Church by the Second Vatican Council. In his concluding segment his comments on the current condition of the Church in Ireland and its prospects for the future are over optimistic.

For whatever reason, there seems to be far less of the altruism and idealism, which inspires religious vocations, in Ireland today than in earlier centuries. Hence the collapse in vocations, which is little short of catastrophic. Perhaps one can take some consolation from his observation that history shows that from time to time, both inside and outside the Church, religious fervour tends to wax and wane. Be assured the curve will rise again.

In this focused and concentrated book the author provides us with many reasons to be proud of our Faith and our Church. The book is a treasury of information on the Christian Churches. Moreover, there are very few persons who will not find it most useful in fact-checking the march of time.