The View

For a long time now Ireland has been battling the Covid-19 pandemic and her people – north and south – have been trying to work out the implications of the UK’s Brexit vote and the NI Protocol. It was never going to be easy. Since the UK left the European Union (EU) there have to be checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain, since by entering Northern Ireland they effectively enter the EU. All very complicated.

There is another complication which has the potential to impact on British-Irish relationships and that is how the legacy of Northern Ireland’s Troubles is addressed. In January 2020 the UK and Ireland agreed the ‘New Decade, New Approach’ deal. It had been agreed in the ‘Stormont House Agreement’ in 2014 that there would be a Historical Investigations Unit “to take forward investigations into outstanding Troubles-related deaths”.

Legislation

The British government said that it would, within 100 days, introduce legislation to implement the Stormont House Agreement. The Irish Government said that it would work with the UK government to support the establishment of the legacy institutions as a matter of urgency, including by introducing necessary implementing legislation in the Oireachtas.

In the event nothing happened. No legislation was introduced.

In recent weeks, particularly following the collapse of the trial of two soldiers accused of the murder of IRA man Joe McCann who was shot in the back in April 1972, suggestions have emerged that the UK government will now move to stop further historic investigations of Troubles deaths. There has been talk of a statute of limitations to prevent investigation of deaths which occurred before the Good Friday Agreement. Both Tánaiste Leo Varadker and Foreign Affairs Minister Simon Coveney have expressed their alarm, and said they oppose any such unilateral action.

It is all complicated by the fact that currently if a person is convicted for a terrorist offence committed before the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ in April 1998, the maximum sentence which will be served is two years. That provision for a limited sentence does not apply to soldiers who served during the Troubles and who are accused of murder or other serious crime.

There has been much prevarication as politicians sought to agree how the legacy of a troubled past should be dealt with, and for decades families of those who died have been waiting to learn exactly what happened to their loved ones.

Inquest

This week the findings of the inquest into the deaths of ten people in Ballymurphy, West Belfast in August 1971 were published. They were Fr Hugh Mullan (38) who was shot dead as he went to help one of the injured; Frank Quinn (19) who tried to help Fr Mullan; Noel Phillips (19); a mother of eight children, Joan Connolly (44), who heard Noel Phillips crying and went to help him; Daniel Teggart (44); Joseph Murphy (41); Eddie Doherty (31); John Laverty (20); Joseph Corr (43); and John McKerr who was 49. Their families waited 50 years for this, and during the inquest soldiers, eyewitnesses, forensic experts and the former head of the British Army gave evidence.

I have been reading pen pictures of those who died written by members of their families in which they tell who the person was and how their death impacted on all the family members, and how those deaths still continue to impact across the generations.

What struck me as I read was the huge sense of loss, and the complexity and awfulness of the consequences of the deaths. These were good people, fathers, a mother, sons – all just trying to live their lives as best they could in the difficult days of 1971. So many Catholics had seen the British Army as protectors when they arrived. Joan Connolly’s daughter described her mother making tea and sandwiches and “having a yarn” with the soldiers. She was one of many.

I learned too that several of these men or their fathers had served in the British Army, in the days before the Troubles; that one man had come from England to live in Ballymurphy; that Joan Connolly’s daughter had been one of the many girls who had gone to army dances in the area the previous year, and fallen in love with a British soldier, married him, and given birth in May 1971 to their baby. Joan Connolly had gone to see her son-in-law who was serving in Flax Street after the baby arrived. There was great happiness. The baby was christened in Ballymurphy. Three months later his grandmother was shot dead by soldiers as she tried to help a dying boy.

Fifty years on, these families have endured more than 100 days of evidence and have been waiting since March 2020 for a verdict. Their pain over the years is unimaginable.

Northern Ireland is full of Troubles-related tragedy, and the trauma which so often comes with tragedy. What people want is to know what happened and why. They want to know if someone was with their loved one when they died. Sometimes they want to know if they said anything, if they suffered.

We are trying to build a new Northern Ireland in the midst of Covid-19 and Brexit, but underpinning it all is the legacy of the Troubles. In a country which proclaims itself as being built firmly on the rule of law, it is vital that the law in all its fullness is allowed to operate. It cannot be right to say to people that the deaths of their loved ones are too old to prosecute.

Very few cases will lead to prosecution, because there will not be the evidence to bring a prosecution. I know this because I have seen many historic death files – some of them so very thin, because there was often really no investigation. In order to prosecute there will need to be new evidence which was not available at the time of any investigation. It is not possible to prosecute using only evidence which was available at the time of the original investigation.

Families understand this. However investigation is needed to find new evidence which may be available, and that is not a job for families. It is a job for investigators.

Report

If there is no new evidence, after investigation, the investigators can produce a report which will tell families what has been found.

No one expects these prosecutions or reports to bring closure for the bereaved; they still have to live with the loss of what was, and of what might have been.

Nevertheless, in a country which proudly proclaims its respect for and adherence to the rule of law, it is essential that we at least try to resolve the unsolved murders of the Troubles. Fighting not to do so has cost huge money over the years. The time has come to use our resources positively and in the interests of justice and truth.

Nuala O’Loan

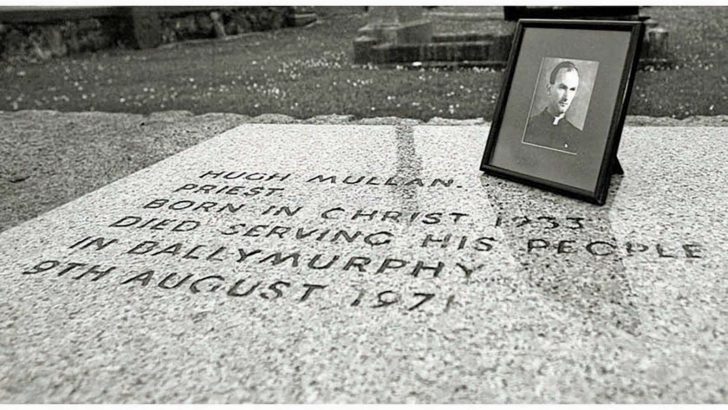

Nuala O’Loan Fr Hugh Mullan’s grave in his native Portaferry, Co. Down. Fr Mullan was shot dead by the British Army as he ministered to a dying man in 1971 in what became known as the

Ballymurphy Massacre.

Fr Hugh Mullan’s grave in his native Portaferry, Co. Down. Fr Mullan was shot dead by the British Army as he ministered to a dying man in 1971 in what became known as the

Ballymurphy Massacre.