In the century since the events on the plateau near the village of Fatima a multitude of books have been published dealing with the apparitions, and the coming century will undoubtedly bring many more.

But many of these books merely provide summaries and comments, rather than new information. Many of the commentaries are couched in terms of today’s anxieties, especially those of North Americans.

To understand about Fatima, the inquirer has to go back to the earlier testimonies and the earliest publications. But among these, it is interesting to note, Irish published books play a leading role.

But first of all to recall what is said to have taken place in May 1917, and the following months.

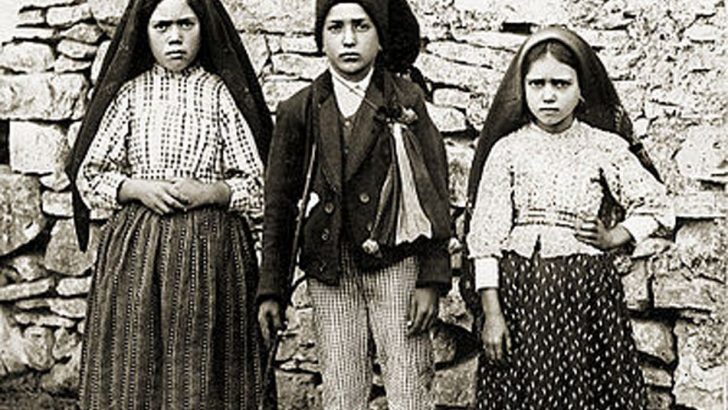

It was in May 1917 that Pope Benedict XV added the title “Queen of Peace” of the Litany of Loreto. Eight days later three small children were out on the plateau of Cova de Irina, herding the family’s flock of sheep, when they had the first of a series of visions. They told their families that a lady had appeared to them; in a later apparition they said the lady had told them she was “the Queen of the Rosary”.

As is nearly always the case, the vision was seen only by the voyants.

Sceptical

Their families at first were sceptical, as parents often are with the strange claims of small children, especially those of a pious nature. However, the visions went on week by week, culminating it an event witnessed by an estimated crowd of 60,000 (some say 70,000) from all over Portugal, when allegedly “the Sun danced”.

These events were reported in the Portuguese papers – especially the last which was front page news in the major Lisbon newspaper O Século, a paper not over friendly to clerical interests. Photographs of the day appeared in Portuguese illustrated news magazines.

Yet oddly enough this news made little impact around the world, passing almost unreported, even in Catholic papers. A generation later people would speak of a conspiracy by the news agencies; but this was not the case. The local clergy and the local bishop were sceptical about the events; indeed the bishop forbade the clergy from playing any part in organising pilgrimages, aside from providing mass for the visitors.

To theological prudence was added a certain amount of caution about aggravating the Republican government’s attitude to these events, which they tried to discourage.

But local people continued to visit the site, where a small chapel was erected. In 1922 after the publication of the first book by a local canon, Dr Manuel Formigao (Os Episodios Maravilhosos de Fatima, never translated into English), and a second book by another author in 1923 (also untranslated), a canonical commission was appointed, which reported back in 1928 to the Bishop of Leiria, who in 1930 declared Our Lady of Fatima worthy of devotion.

By 1930 a proper church had been built at Cova de Irina, paid for out of contributions, rather than parish funds. It was only after this that Fatima slowly became a place of international pilgrimage. In 1930 one procession was estimated at nearly half a million.

Yet abroad even Catholic papers continued to refer to Fatima as the “Lourdes of Portugal” – an indication of its status at the time. Portugal was for the other Europeans a far away country of which they knew little, to adapt a famous expression of the day.

By now accounts of the events, albeit at second hand, had begun to appear in English. The first publication in Ireland was a small pamphlet Our Lady of Fatima (Irish Messenger Office, 1932) by Senator Helena Concannon, the well-known religious writer.

However, the most important of these publications was by Monsignor Finbar Ryan, the titular archbishop of Gabula. Our Lady of Fatima was a substantial volume published in Ireland in October 1939, and in Australia, by the long established firm of Brown and Nolan. It was issued by Herder in the USA.

Bishop Ryan had been lecturing on Fatima for many years, and his book was one of the most influential ever published on the shrine.

The book passed through many editions, with even a Gaelic translation appearing from the Irish Government Stationary Office in 1948. Thus Ireland played a significant role in the spreading the devotion to a now much visited shrine.

Irish books on Fatima reached a peak in 1950, but then faded away to almost nothing, the last being published by its author himself in 2000.

This trend was an indication of the changing nature of religion in modern Ireland, even then beginning to decline.

But by middle of the last century a wave of publications, largely from the USA, was sweeping the world.

One of these, still highly regarded by many and as influential as Bishop Ryan’s was Our Lady of Fatima (1947) – which is still in print (Image, $15.00). This was by Professor William Thomas Walsh, a writer very much of his period, whose other books have, however, been criticised for their anti-Semiticism.

This raises a point regarding the care readers need to take reading older books on Fatima.

Many books from the past were issued with an imprimateur, but this merely indicated that a local ecclesiastical censor found them free of doctrinal error; it does not mean that the Church approved of their social, political, or philosophical outlook. Nor is such a declaration a protection from condemnation by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Since 1950, Marian theology has developed, deepening an awareness of the role of the Blessed Virgin in the life of the Church, in a wider context of ever increasing insight. This often gives it a different aspect to older views.

But what really sets Fatima apart and began the great wave of devotion in the late 1940s and early 1950s was the personal interest of Pope Pius XII, through what might be called his direct patronage of the shrine. He was influenced by a visionary experience of his own in the gardens of the Vatican. He experienced for himself a vision of the sun “dancing” akin to that seen at Fatima he thought; an event which was later confirmed by his spokesman.

The first extended theological treatment of Fatima was the work of an eminent scholar, the Belgian Jesuit theologian, Fr Dhanis, who had a distinguished career, as professor of theologies at Louvain (1933 to 1949), later at the Gregorian University in Rome (1949 to 1971), of which he was rector (1963 to 1966). He died in 1978. He was, from the Vatican point of view, a “safe pair of hands”: in The Message of Fatima (2000) by Cardinal Ratzinger, Fr Dhanis is the single theological authority quoted.

Dhanis discerned stages in the development of what we know about Fatima. Stage I derived from the original testimonies gathered for the diocesan commission, on which the recognition of the devotion was based.

Documents

Stage II derived from the memoirs of Sr Lucia, written in stages many years later. These documents have been examined for the process of her canonisation.

But the separation of her canonisation from that of her cousins derives from the doubts in the minds of some theologians (perhaps even Benedict XVI) about the trustworthiness as historical evidence of testimonies recorded so late, and seemingly not presented before the original commission.

The whole matter of the three secrets of Fatima, about which theories of conspiracy have abounded to the embarrassment of the Vatican, is bound up with Sr Lucia’s later testimony. On these matters we can see controversy continuing.

One most significant book on Fatima has never been translated from the Portuguese. This is Fatima: Segredos, Graças, Mistérios by Antero de Figueiredo (Paulus Editora, €12.90), a recognised figure of some standing in 20th-Century Portuguese literature. Published in 1936, this is one of several spiritual books the author wrote.

A book distinguished for its literary merit, which reminds one of an author such as Huysmans in La Cathedrale. Theirs are books of great significance, which are, however, far removed from the pious publications which so many prefer to read.

But the lack of a translation of Antero de Figueiredo’s book shows that there are still things to be discovered and read and appreciated, even after a century of discussion on of the meaning of the events at Fatima.

If we are to try and fix the meaning of Fatima that comes from even a brief survey of the literature since 1917 it would be essentially a message of peace, peace between cultures, peace between nations, peace between individuals, symbolised for Christians by the maternal anxiety of the mother of Jesus for the all the children of humanity.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello