Journey Without Maps,

a travel book by Graham Greene

(Vintage Classics. £14.99)

At the end of January President Trump issued a proclamation on Black History Month promoting to all officials and members of the public that it might concern, naming as he did so a short roster of notable Black Americans.

But it is noticeable that the author of the proclamation, hardly Mr Trump himself, cannot bring himself to write ‘Black American’, writing instead black American, with small ‘b’. This is the same kind of insensitivity that uses a small ‘j’ when using the word ‘Jew’. It is a dead give away of prejudice and lack of real respect.

In the United States many government departments seem to be engaged in obliterating Black History Month as part of the new administration’s campaign against ‘DEI’, that is to say “diversity, equity and inclusion”.

President Trump is determined to fold back and make unseen the achievements of many decades of effort to see all Americans for what they really are. The ideal American is now a white male, of Northern European, perhaps even Irish, extraction, living in a suburban quarter far removed from inner city poverty.

But at the same time President Trump is planning a invasion of Panama, so it would seem, to seize the Panama Canal, which he says “We built”, meaning these fine upstanding white American males, destined to run the world.

Claims

These claims hardly agree with the actual history of the Panama Canal as the history books and accounts of the day reveal it to have been. One such book, easily accessible online, by bestselling British author David Howarth, provides an independent source of information.

The Canal was initially the idea of the French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, creator of the Suez Canal, and was originally begun by a French company. However, technical difficulties and devious dealings of all kinds, led to the collapse of the French enterprise in a political and social scandal that rocked France, indeed the world.

The enterprise was later renewed by the North Americans, who carried it through in a decade or so, with one notable achievement, the overcoming of the malaria which was spread in the tropical region through which the canal passed. It had been discovered by the British in Africa that the carrier of the disease was the mosquito, the destruction of which in the swampy regions of the world has become a crusade.

Liberia is in essence an American colonial enterprise, a carved-out region to which liberated slaves during the post Civil War Reconstruction would be shipped as colonists”

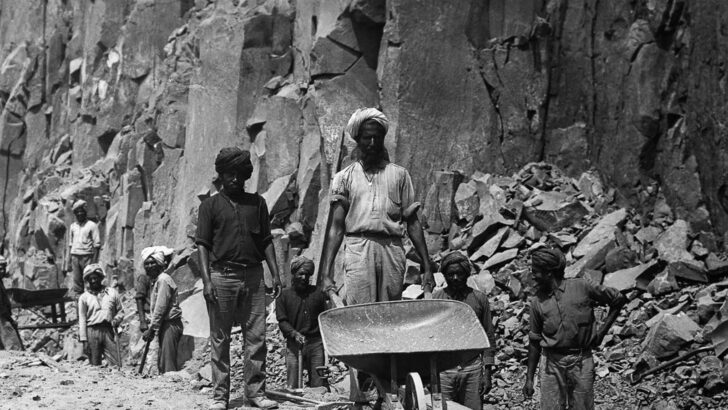

But who actually built it. Here (see illustration) is a photograph of some of those who did the actual digging. They were Blacks, the descendants of American Blacks who are not themselves American. They were citizens rather than the Republic of Liberia, a nation state in West Africa, which was a colony of American foundation, intended to move the Blacks out of the US to their “real country”. This history of Liberia strangely enough seems of little interest to American Blacks. They are rightly concerned more with slavery and the origins of Black America. But Liberia is a different matter.

Liberia is in essence an American colonial enterprise, a carved-out region to which liberated slaves during the post Civil War Reconstruction would be shipped as colonists. Once in Africa, with some American resources behind them, they became the rulers of the actual local Africans.

Classes

To this day in Monroeville – named for James Monroe the creator of the ‘Monroe Doctrine’ in 1823 rejecting any new European colonies in the Americas – there are two classes of people: the American derived elite, and the lower classes of native Africans.

It was from Liberia that the American entrepreneurs creating the Panama Canal derived the labourers to do the actual digging. To some it might recall what many think the Bible says about the Hebrews being forced to built the pyramids: a “fact of history” which seems to be untrue by the way – the pyramids archaeologists now think, were built by free Egyptians, ancestors of to-days Christian Copts, out of pure religious devotion.

So the Panama Canal was built, not by “Us” in Trump’s sense: but by Liberian Blacks in virtual American servitude. The sons and grandsons of the liberated American slaves were effectively re-enslaved for use in Panama. The Panama Canal was finally opened with great American rejoicing in 1914. It meant that ships no longer had to pass through the dangerous seas around Cape Horn at the southern tail end of South American.

Anyone wishing to have a view of ‘colonial Liberia’ from an acute and committed Catholic point of view should read Graham Greene’s Journey Without Maps”

But there was a cost: some 40,000 labourers were utilised, and officially, far more according to some historians. These numbers also included other Blacks – but still with background in slavery – from the various West Indian islands.

If he were truly interested in Panama, truly interested in ‘Black History Month’ and the Panama Canal, President Trump might be keen to mention some of these facts.

Anyone wishing to have a view of “colonial Liberia” from an acute and committed Catholic point of view should read Graham Greene’s Journey Without Maps, a travel book first published in 1936, which is among his finest non-fiction books.

Also of relevance about the Panama Canal saga is The Golden Isthmus by David Howarth ( London: William Collins, 1966), widely available online.

Photographic images of the Black labourers from Liberia and the West Indies on the Panama Canal can be found on the US National Archives website, using the identifier ‘535444’ and ‘535446’; but visit soon as they might well be removed in line with the current outlook in Washington.

Last week President Trump fired the director of the National Archives in Washington.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Building the Panama Canal

Building the Panama Canal