Living with uncertainty is key for Christians, Alister McGrath tells Jason Osborne

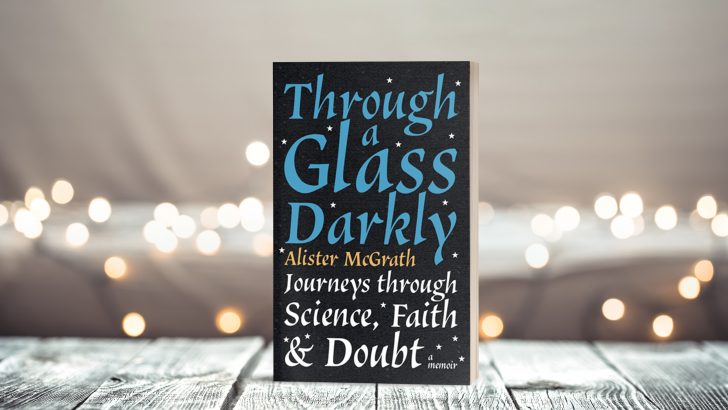

In his latest book, Through a Glass Darkly: Journeys through Science, Faith & Doubt, famed theologian and author Alister McGrath recalls a quote attributed to the mastermind behind the Manhattan Project – the American quest to create the atomic bomb during the Second World War – Robert J. Oppenheimer. He tells of how he came across a phrase attributed to Oppenheimer in a newspaper interview, in which he said the best way to communicate something is to “wrap it up in a person”.

A short few decades later, Mr McGrath himself has come to be wrapped up with the ideas he has spent his life trying to communicate – the notion that science, reason and faith are not only compatible, they naturally hold together.

Having identified the modern malaise of thinking that science and faith are incompatible, Mr McGrath has sought to reframe this conversation”

Speaking to The Irish Catholic, Mr McGrath told of the reaction his latest offering on the apologetics front has garnered:

“Well it’s very interesting. I actually was in one of these online lectures, presenting this book and I think about four thousand people tuned in to talk about it, and they were very receptive to this because they felt that they were fed up being bombarded with what seemed to be certainties and yet, when you look at them a bit more closely, they weren’t certainties.

“And I thought, it’s so honest to say, ‘Look, you can believe things without being absolutely able to prove them. That’s just the way things are’. And that doesn’t mean you believe anything you like, it means you have to ask, ‘What are the reasons for this?’ But nevertheless, you do not need to be able to offer absolute proof because you get that only in mathematics, so a lot of people find this hugely refreshing. Someone last night said it was ‘liberating’.”

Ireland’s last census in 2016 saw an increase of 73.6% in the number of people identifying by their lack of religion”

The central thrust of his book, and much of his career, can be summed up by the title – a journey through science, faith and doubt, and the relationship between the three. Having identified the modern malaise of thinking that science and faith are incompatible, Mr McGrath has sought to reframe this conversation.

Christianity

A strong proponent of the idea that the various sciences help us to examine different aspects of reality, Mr McGrath takes the rare position in the public forum that Christianity is the “golden thread” running through the world – a thread which helps us to make sense of the “great blooming, buzzing confusion” of the world. He described his understanding of this by saying:

“Well, not everyone would agree with me on this, so this is me and a few other people as well, but I think it’s very important because what you’re really saying is that despite the world appearing fragmented and disconnected, actually when you see it in the right way, it all hangs together.

“And if you like, there’s a thread linking everything, and that imagery is quite helpful because people I think very often feel that they are lost in a, sort of, incoherent, complete mess of a world, and finding something that says, ‘Look, actually although it looks fragmented, although it looks completely chaotic, actually you can see meaning and order there and you know you can fit into this and live meaningfully in it.’ And that’s so important I think, just for people to be able to feel that they can exist in the middle of a chaotic world because they can sense that there is something deeper behind it and they’ve found it and they’re hanging onto it.”

There has been a seven-fold increase in this category since 1991, when the figure stood at 67,413”

If there’s any doubt as to whether people really do see the world as a messy, haphazard place, census data from both our own shores and around the world assures us that there has never been such a swell in the numbers of people professing atheism, agnosticism, and “no religion”. Ireland’s last census in 2016 saw an increase of 73.6% in the number of people identifying by their lack of religion, a rise from 277,237 in 2011 to 481,388 in 2016. There has been a seven-fold increase in this category since 1991, when the figure stood at 67,413.

Business of living

At times, the asking and answering of philosophical questions can seem detached from the business of living in the world, but if the rise of atheism and agnosticism are to be remedied, intellectually rigorous answers must be given to questions which see science and faith clashing.

Mr McGrath sees real opportunity for those questions to arise during the unorthodox times through which we find ourselves living:

“People feel, ‘What’s going on? I just don’t know what’s happening.’ And actually, there’s been an erosion of so many cultural certainties by the coronavirus episode, for example, people say, ‘Oh, we’ll be able to get on top of this, we can master this,’ and we haven’t been able to. I mean, you’ve got a lockdown in Ireland, we’ve got very much the same thing happening here (England) and we’re just realising we’re confronted with something we can’t control. And, you know, that tells us something about ourselves. What I’m saying is I think that, really, you need a worldview to be able to help you cope with that and I think that the book tries to explain how this actually helps you do that.”

His youth

The necessity of having a “bigger picture” or a coherent worldview was highlighted to Mr McGrath by his youthful interactions with Marxism – in his book, he details his fascination with it initially as a college student, before finding it lacking in some crucial ways. However, there were some elements which he found incredibly useful, and which convinced him that anything less than a grand theory of the world, such as Christianity, was not to be bothered with.

“I mean I think one of the reasons I was drawn to it (Marxism) was it did give me this bigger way of looking at things, this connectedness of things, and also, if I could put it like this, it gave me a sense of my role as an agent. In other words: here’s the way things are going, here’s what I can do to move them along. I think that that’s one of the tests I think I would apply to any worldview: ‘Does it actually help you position yourself and figure out what you can do?’ And so Marxism, I think, I found very engaging. In the end, I reduced it to a very helpful way of looking at things but nothing more than that, but it was helpful in some ways.

He continued, “It created an appetite within me. I felt, ‘Look, I can’t go back to something that’s trivial or very, very local – I want something bigger than that’. And discovering this bigger view of Christianity really, really excited me intellectually, so it was really quite liberating to use that word again.”

Liberation

The liberation he spoke of was not just intellectual, but spiritual and emotional. When asked what practical changes seeing the world through eyes of faith effects, he responded, “Well let me tell you the big change which I noticed: I stopped feeling the need to justify myself. I stopped feeling the need to prove myself. I just said, ‘If Christianity is right, I’m accepted as I am.’ And actually, I said, ‘I can live with myself’. And so, in effect, although academically obviously I have to achieve certain things, there’s not this intense feeling, ‘I have to perform, I have to deliver,’ – a sort of narcissistic introversion. A much more, just you know, I am who I am, God loves me, and now let’s see what I can do to help things along.”

The increasing polarisation of political discourse is a direct result of an inability to comfortably live with uncertainty”

While Mr McGrath’s latest book examines the interplay of faith and science, it also explores the role of doubt. He sees doubt as being an essential part of the human condition, acknowledging the fact that we can know very little for certain. On occasion in the book, St Paul’s maxim from 1 Corinthians 13:12 is quoted, which describes our vision in this world as seeing through a glass darkly. The quote from which the title of the book is taken, learning to live with unanswered questions and developing a capacity for mystery has proven a large part of Mr McGrath’s struggle.

“I think it manifests itself in the fact that I’m very happy to live with unanswered questions. In other words, questions that are good questions that I’m thinking about, I haven’t yet sorted them out, but I say, ‘I can live with this degree of uncertainty’. And so, as an academic, I think it’s very healthy because it means I don’t need to close down discussions prematurely, I can keep them open, I can say, ‘I’m still not sure about this, I think it might be this, it might be that,’ but I don’t feel under pressure to, kind of, close things down and become dogmatic. I, kind of, keep things open.

A degree of fluidity

“If you like, I think I’ve sorted out the things that really matter and I can enjoy a degree of fluidity or uncertainty about other things as well. So I think actually, if you’re an academic, it’s quite good for you because it means that you are open to people who have enquiring minds to explore things with them. And of course, if you’re an academic teaching as I am at Oxford, then students really like that because it means they go to you and they talk things through with you.”

Christmas might be a time just for reflecting; how can we learn from this? How can we grow through this?”

Again, Mr McGrath sees the issue of comfortability with uncertainty not only as an academic concern, but as one with which everyone must come to terms. The increasing polarisation of political discourse is a direct result of an inability to comfortably live with uncertainty.

“I think it’s part of the human condition, but I always worry that when you have uncertainty, when you have polarisation, then people begin to adopt very dogmatic worldviews. Sometimes religious, but usually political I have to say. And, you know, it’s like 1930’s when really these very aggressive ideologies began to take root and, you know, people bought into them because they gave them certainty. And of course that’s what worries me, that actually, the certainty may be something that’s imposed on you – not generated by the ideas themselves.”

The antidote to the incessant ratcheting up of tensions may be right under our noses however – relationship. Asked about how the Christmas season speaks to the year we’ve endured, Mr McGrath admitted that it was an issue he’d been reflecting on himself.

Celebration of God

“It is something that I’ve been thinking about because, you know, I understand my wife and I, we have grandchildren, we probably won’t be seeing them at Christmas so I think it’s one of those things – Christmas has become not simply a celebration of God entering into the world, but (it’s about) the importance of relationality in the world. In other words, how important our relationships with other people are. Our family, our friends and God. And how actually we need those relationships to survive.

“And what I’ve been thinking myself is, in this difficult time when my wife and I are on our own a lot, actually, it’s very important to be able to say that our relationship with God has not been disrupted by this virus. If you like, it’s almost like it’s a period of exile. You know, we’re cut off from the buildings people used to know, and yet we’re able to deepen our relationship with God so, for me it’s a time of reflection, to say, ‘Look, this is a difficult time but here’s what my thinking is. It’s a difficult time from which we can learn and through which we can grow. And so what I’m hoping is that at the end of this, I and many, many others will emerge from this stronger and wiser. That’s what I’m hoping. Christmas might be a time just for reflecting; how can we learn from this? How can we grow through this? Because otherwise we see this simply as something negative. It might be something which we can learn through.”

As is in keeping with his worldview – knowing that all roads lead to God, he has taken the opportunity to grow in love of God and his created order in what ways he can during lockdown.

And actually, it means that when normality returns, we’ll be able to appreciate it all the more”

“I’ve been forced to, in effect, not be able to go to church. I’m able to go to church online, but it’s not the same. But what it’s forced me to do is to say, ‘Right, what am I going to do?’ Well, the answer is I’m going to read some books on spirituality and so on that I’ve been longing to read for ages. And interestingly, one thing I’m doing is I’m reading through Mark’s Gospel in the company of somebody I knew, he wrote a commentary on Mark and he’s now dead, but actually it’s very, very good to feel there was somebody accompanying me as I read the text. And so what I think we have to do is say, ‘This isn’t a normal time, but we have to adapt to it’.

Normality

“And actually, it means that when normality returns, we’ll be able to appreciate it all the more. Maybe we just took things for granted. We’ve realised they aren’t as secure as we thought so when they come back, we’ll appreciate them even more. It’s a bit like the people of Jerusalem in Babylon. Longing to go home and realising how important it was, and maybe they didn’t realise that at the time when they were there.”