by John F. Deane

Seamus Heaney famously said: “The biggest change in my lifetime has been the evaporation of the transcendent from all our discourse and our sense of human destiny.”

Heaney was speaking out of a time when Christian faith was static, and had been static for centuries. Faith in Christ had only begun to embrace the sciences, the rise of consciousness, awareness of evolution and its consequences to faith.

Then, in a book recently published, He Held Radical Light (FSG, New York), the former editor of the magazine Poetry Chicago, Christian Wiman, a powerful poet in his own right, tells of a reading Seamus gave, one of his last, in Chicago.

He recounts how he “met Seamus Heaney in person only once”, at a dinner given after that reading. They sat together and Seamus mentioned he had been reading the proofs of Wiman’s memoir, My Bright Abyss, where Wiman struggles with suffering and faith.

Wiman was moved to know he was being read. Later in the dinner, “and in the middle of a conversation that had nothing whatsoever to do with religious faith, he leaned over to me and said – very quietly, he seemed frail to me – that he felt caught between the old forms of faith that he had grown up with in Northern Ireland and some new dispensation that had not yet emerged”.

I find that “new dispensation” emerging beautifully in this new collection by Padraig J. Daly, himself a worthy servant of a more realised faith pertinent to our times.

From Heaney’s collection titled Seeing Things, we move on to Daly’s extension of faith in Glimpsing More. So: Does the transcendent need to be rescued? Only if our definition of that word suggests something divine away beyond our experience, and only if we do not see, in the most mundane and most material things in our experience, just matter, rock, stone, wood, flesh. Daly’s new book tells us where he hopes to glimpse more:

My prayer

My prayer is the prayer of the street:

Of addicts berating the dark,

Of crows descending for discarded suppers,

Of football crowds and birthday feasts,

Swish of buses, horses’ clop,

Neon night surrendering to hopeful dawn.

Mary’s deep joy as she watches her baby Jesus sleeping is not merely the awareness that here is something divine and transcendent: “She watches his belly Move up and down in sleep. She touches his skin. She feels her body will fall asunder with happiness.” From the beginning of Daly’s work in poetry, he has paid homage to the everyday, the physical world in which we live and move and have our being.

Poetry, for Daly, does not come “in logic’s barren highways”, nor in seeking the strange, the beyond, the unutterable; it comes by being permeable to the world around us, by remaining open to the possibility of the transcendent, like catching a rare butterfly in a net, the gift, the given, when it offers itself.

The poems remain optimistic therefore, without insisting, that it is the wealth of the experience offered through the richness of his language and the unique ease and rhythmic music of the words, phrases, cadences he uses, that convince us of the reality of this, and of the transcendent.

And it is in this awe and humility before the wonderful nearness of the earth that gives this priest his power to convince us, as it is the poetry he finds in that nearness that presents his God to him, and, without presumption, he is the prophet standing between us and that God and presenting the wonder:

You are too much for me,

Great God:

My mind is in flitters considering You.

How do I, a fleck in creation,

Presume upon You?

And what convinces me of

Your care

For the lowliest, meanest

of us?

In a short sequence that insists on his age: 76, 77, 78 and 79, he writes: “I will be gone before long; I do not fear extinction; Nor any afterwards: I trust in transcendent tenderness”. By now, after so many wonderful real and astonishingly beautiful poems, he deserves those last lines.

It is important to note that, as we all know, everything is not rose wine on the patio; as a priest, this poet is intensely aware of the suffering of humanity;

Middleman between God

and themselves,

They assail me with griefs

and broken hearts,

Convinced that I have sway

with Him,

Who am emptier far than

they.

A constant theme in Daly’s poetry is that God does not appear to be listening to our prayers;

Do You not hear their

voices,

Good My Lord?

What is the mystery of Your

unlistening?

So, this poetry of praise, of transcendence, of faith in nature and matter, is accompanied by elegy and moments of doubt. There is a balance that convinces the reader even more of the worth and truth of these

glimpses into the beyond, into the more. Poems to and about children add a richly human warmth to the work, as well as poems in memory of his mother, and of friends who have died. Poems of love for places and people that are rich in detail, and in the music of the language. This music is often enhanced by the sounds and references that old Irish names and words offer. It is a collection varied, profound and enhancing

of our efforts to glimpse what is good in the world.

Response

There is one short poem that encapsulates beautifully Daly’s poetic response to the loss of transcendence Heaney outlined; a response that is deeply satisfying, and profoundly real.

Faith (For Rian)

There is no great blast of light

Breaking across my

brain,

Filling me with certitude;

Merely, fleeting glimpses

of more –

In a lift of dunlins,

In sun slanting through

pines,

In a plane labouring

across sky,

A boat labouring out to

sea,

In the gobsmacking

miracle of a human child.

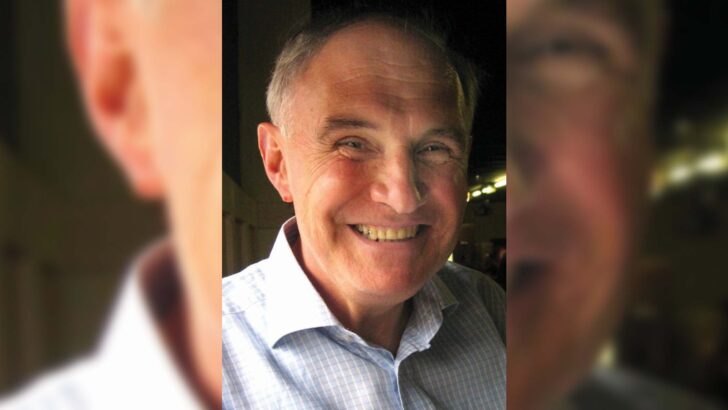

Padraig Daly.

Padraig Daly.