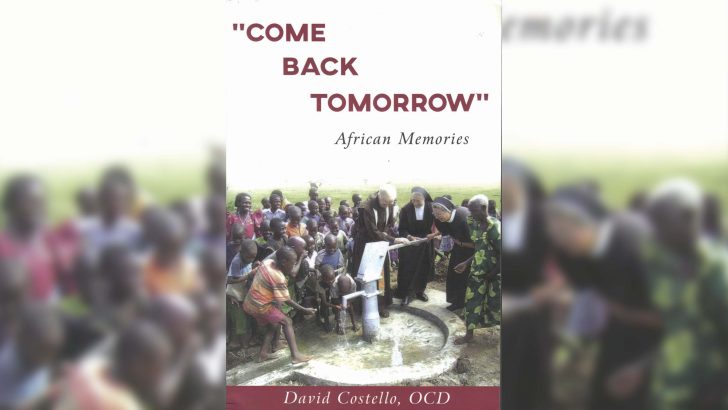

“Come back tomorrow”: African Memories by David Costello OCD (Wheat Mark Publishing, Tucson, Arizona, USA, US$11.95; also available on Amazon in paperback and ebook)

Over the years I have found the recollections of missionaries, and they come in a great many shapes and sizes, are always of interest. They cast a great deal of light not only on the remoter and lesser known parts of the world for those of us who live our lives in “the North” rather than the often deprived “South”. These days so long after the great flush of countries gaining independence in the 1960s, deprivation is less and less the result of colonial plundering than the greed of local figures of power.

Fr David Costello is a Discalced Carmelite who was an Irish missionary, and still is in a different capacity. Back in April he celebrated his 60 years of priesthood. These days he serves as a priest in residence at Santa Cruz Parish in Tucson, Arizona. Though Arizona has a dry warm climate, a far cry from the humid days and nights he passed in East Africa.

Jubilee

That diamond jubilee focused his mind on writing these memories, which deal in large measure with his life in Africa, in Uganda and Kenya. But they begin back in Ireland. He was born in Castlemartyr in Cork, and I think this is the first book I have ever encountered that describes life in that pretty town, which has complicated history of its own, though today it is perhaps more widely known for the celebrated golf course attached to the great house.

Some three chapters of over 10 pages cover his early life in Ireland, then on to the years he had in Uganda – where famously some of the earliest Catholic missionaries in the 19th Century were martyred for their faith and witness.

However some eight pages or so are devoted to the nature of the Carmelite charism and to the spiritual and human matters of the personal and social development of both the priest and his people. These pages are rather at the heart of what Fr Costello has to say, as they can be appreciated by Christians at home as well as by his colleagues in the field.

Injustice

The injustice that is spread across Africa cries out for change. Those following the current Presidential election in Kenya will realise that the current social and political problems of that large country are a problem not to be dealt with overnight. Uganda, too, has had long periods of both tragedy and dictatorship, the fate of all too many African states, where traditional custom and obligation have been modernised but where the social order of the tribe has barely been replaced by the notion of civic society. (The casual way he reports how he and one of his colleagues provided a traffic policeman with a personal pourboire (tip) to deal with a driving offence, illustrates how power is exerted in Africa down to the lowest level. It is the way things are done in Africa.)

Africa is a continent of striking contrasts. On one page (p. 156) he writes the homeless in the United States “are more prosperous than most people in Uganda” and “have access to all their essential needs” – a claim many since Michael Harrison and Dorothy Day have disputed.

But on the facing page a colleague rightly celebrates the energy, even joy, of a home for mentally challenged children. Though people speak casually of the untapped resources of Africa, they think too often in terms of gold, diamonds and minerals essential to technology. But the real untapped resource of Africa is its people and their courage, and how even in what seems a sad and miserable situation, they can laugh and enjoy themselves.

At the heart of the book is an exploration of the Carmelite mission in the light of Karl Rahner’s famous dictum that “The Christian of the New Millennium will be mystic or he will not exist at all”. He refers to John Walligo, the Ugandan theologian, who contributes to “the flourishing area of Christology”. The question is “Who is Jesus for the people of Africa. What image of Jesus makes sense for Africa? Jesus as Healer, as Ancestor and Elder Brother, as Chief and as Liberator.” Walligo selected to write about “Jesus the Suffering Servant” in The Faces of Jesus in Africa.

Accretions

Only by striking away the European accretions to the true image of Jesus as Middle Eastern can Africa begin to see the black face of Jesus, it seems. If the future of Christianity is in Africa, as so many claim, impressed by the strongly traditional address of some senior prelates, that “black face of the Church” will have many surprises for the world which will owe little to the 12th Century to which so many look back in nostalgia for certainties that are gone.

There are many comments fertile for further thought in these pages. The publishers speak of this book as a resource for future missionaries; but those missionaries may not be to Africa, but to Europe and to North America, as I think Fr Costello seems to suspect.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello