“You Will Dye at Midnight”: Threatening Letters in Victorian Ireland

by Donal P. McCracken (Eastwood, €20.00)

The news media these days are filled with reports of threats of death and violence being made, not just against celebrities, politicians, media stars, bishops, and such like, but against even internet users careless enough to expose themselves to comment and abuse. These activities give a special interest to this account of poisoned pen letters in the Land War of the 1880s.

Donal P. McCracken is a South African who has written historical studies relating to Ireland in the course of his long academic career. The research for this present book was, he says, based on research carried under a grant from the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the University of KwaZulu-Natal – an instance of the third word critically exploring the sins of the first world.

Threatening

He claims chillingly enough that “Victorian Ireland was a global champion of the threatening letters.” The book, however, sees the letters discussed in these pages, which survive in government and police files in our National Archives, as flourishing in the days of the land war, and fading away afterwards with occasional outbreak as in the house burnings of the civil war.

But this is surely not the case. The letters which can be seen as part of the national struggle certainly, but these are also an aspect of the ever present poisoned pen letters syndrome, those anonymous and vicious screeds with which all police services are familiar. Far from being an unusual activity, they were in fact part of a commonplace of life, that is still with us.

He was a recognised authority with a world-wide reputation. But then he had a lot of material to learn from, culled from ordinary Irish life”

I was surprised to see that he does not refer to that classic work Forged, Anonymous and Suspected Documents (London, 1931) by Captain Arthur J. Quirke , an Irish Army intelligence officer who was handwriting analyst to the Department of Justice, to the Attorney-General and the new police, and a witness in many Free State trials about poisoned pen letters. He was a recognised authority with a world-wide reputation. But then he had a lot of material to learn from, culled from ordinary Irish life.

Nor does the author allude to the passing references in novels and memoirs (I am thinking here of T. H. White, who lived in Ireland during the Emergency) to how ubiquitous such letters were in rural Ireland.

Corbeau

Certainly in rural France the activities of the local “Corbeau”, as poisoned pen letter writers are known there. Such threatening letters are an aspect of all troubled rural societies: warning letters of the KKK in the defeated Southern States after the Civil War for another instance.

But even more important surely is the fact that the present day internet which connects McLuhan’s “Global Village” is rife with threats, abuse and splenic diatribes very similar to the historical village communities of Europe.

Victorian Ireland then was not unique. We are dealing here with a long existing aspect of human nature. The pasquinades of Renaissance Rome, laid at the foot of a “talking statue” attacked freely but anonymously anyone in the public eye.

The common factor is human nature, for psychology of all of this goes back a much longer way. Such a universal habit is a human characteristic. It is perhaps, a Christian might feel, a matter for the moral theologian as much as the police.

Dr McCracken’s book says more than he realises, and casts a flood of light on the present, and the present re- illuminates the past”

It is a question raised in McCracken’s book as to whether the threats were carried out. Some in the 1880s and later were in fact carried through. But the sense of fear engendered for political or social purposes was real.

The Irish public figures who are outspoken about threats online today are in a very long tradition.

Dr McCracken’s book says more than he realises, and casts a flood of light on the present, and the present re- illuminates the past. The samples of the letters he illustrates have their echoes today.

In time someone will find the answer. Or rather, accept the theological answer we have already, but chose to ignore.

Peter Costello

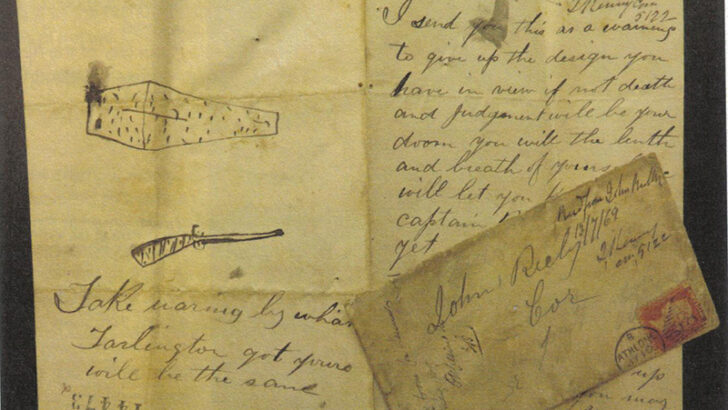

Peter Costello A threatening letter written in 1869, typical of the angry missives sent during troubled times in Victorian Ireland. (National Archives of Ireland)

A threatening letter written in 1869, typical of the angry missives sent during troubled times in Victorian Ireland. (National Archives of Ireland)