Gerald Boland: A Life

by Stephen Kelly (Eastwood Books / Wordwell, €20.00 / £18.99)

Enoch Powell famously wrote that “all political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure”. The career of Gerald Boland was no exception.

A senior figure in the Fianna Fáil party from its foundation in 1926 until his resignation in 1971 and a member of every Fianna Fáil government from 1932 to 1954, he is long overdue a biography. This fine study by Stephen Kelly, of Liverpool Hope University, is therefore greatly to be welcomed.

Boland was born in Manchester in 1885 to an Irish family with deep Fenian roots; his father had links to the Invincibles who murdered Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Burke in the Phoenix Park in 1882.

Growing up in Dublin, his involvement in advanced nationalist movements began at an early age. His role in the 1916 Rising, in the War of Independence and in the Civil War on the anti-Treaty side, while significant, was less noteworthy than that of his younger and more charismatic brother, Harry.

Harry Boland became a republican martyr when he was killed in doubtful circumstances during the Civil War.

Shortly before Harry’s death, Gerald had been captured by Free State troops near Blessington, Co. Wicklow.

He would not be released until July 1924, and Kelly records that he was interned for longer than any other anti-Treaty prisoner.

Beginning

During his imprisonment, he and fellow prisoners went on a hunger strike that lasted 40 days in a futile attempt to secure their release. While imprisoned, he was elected TD for Roscommon to fill the seat which had been held by his late brother. He would retain that seat until 1961, after which he served two terms in Seanad Éireann.

In the early days of Fianna Fáil, Boland and Seán Lemass were appointed joint honorary secretaries and tasked with setting up the organisation nationwide and preparing for elections.

“They were a remarkably successful team, and their efforts bore fruit quickly when Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932, six years after the foundation of the party”

They were a remarkably successful team, and their efforts bore fruit quickly when Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932, six years after the foundation of the party and less than ten years after the anti-Treatyites had been decisively beaten in the Civil War.

Boland had been one of the first within Fianna Fáil to call for the abandonment of the policy of abstention from Dáil Éireann, his view being that the party would otherwise be irrelevant.

“Boland pursued a particularly hard line against the IRA”

His government service was successively as Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, Minister for Lands and, most controversially, Minister for Justice. Kelly gives a full account of his achievements in these offices.

As Minister for Justice from 1939 to 1948, Boland pursued a particularly hard line against the IRA: six IRA members were executed and three were allowed to die on hunger strike on his watch.

Kelly argues that Boland believed his stance was necessary in order to safeguard Irish neutrality during the Second World War in view of IRA dalliance with Nazi Germany – and so did the government.

However, as Kelly observes, “for many of Boland’s critics, his stern – some have called it ruthless – suppression of the IRA looked like a classic example of the poacher-turned-gamekeeper, given his own revolutionary background”.

Conflict

On other matters, Boland could be more liberal than many of his Fianna Fáil colleagues. For instance, he opposed the initial draft of the religion article (Article 44) in the 1937 constitution as sectarian and, in his own words, “equivalent to the expulsion from our history of great [Protestant] Irishmen”.

His objections resulted in the compromise text that was eventually adopted recognising the “special position” of the Church but going no further than that.

In the 1950s, Boland was increasingly at odds with Seán Lemass’ efforts to modernise the Irish economy and to move away from outdated policies in other areas, especially in relation to Irish reunification.

“The struggle for power between these two titans in de Valera’s declining years as leader of Fianna Fáil led to Boland being dropped from the cabinet”

Boland regarded much of this as contrary to the core values of Fianna Fáil. The struggle for power between these two titans in de Valera’s declining years as leader of Fianna Fáil led to Boland being dropped from the cabinet at Lemass’ insistence when de Valera formed his last government in 1957 and it presaged the divisions in Fianna Fáil which threatened to break up the party in 1970 when Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney were sacked from the government on suspicion of being involved in a plot to secure arms for nationalists in Northern Ireland.

Gerald’s son, Kevin – who had replaced him in the cabinet in 1957 – resigned from the government in sympathy with Haughey and Blaney, and was supported in this by his father. Both father and son later resigned from Fianna Fáil. Gerald died soon afterwards, in 1973.

Stephen Kelly’s biography makes extensive use of Gerald Boland’s unpublished memoir and associated personal papers. His book is, accordingly, an important contribution to the historiography of the first half-century of independent Ireland.

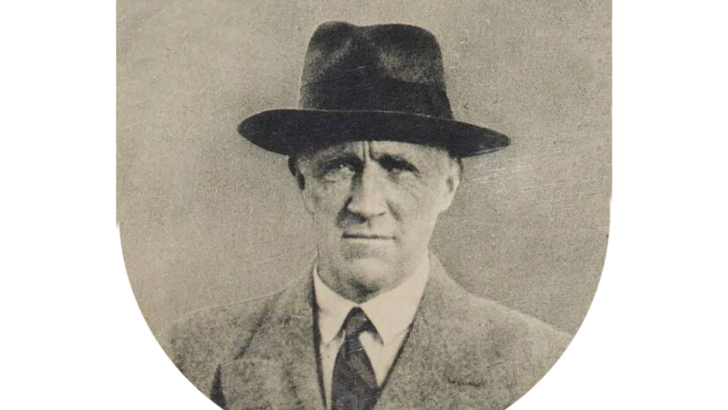

Gerald Boland, about 1932, when his party came into power and he became a minister

Gerald Boland, about 1932, when his party came into power and he became a minister