There’s an oddity in the gospels that begs for an explanation: Jesus, it seems, doesn’t want people to know his true identity as the Christ, the Messiah. He keeps warning people not to reveal that he is the Messiah. Why?

Some scholars refer to this as “the messianic secret”, suggesting that Jesus did not want others to know his true identity until the conditions were ripe for it. There’s some truth in that there’s a right moment for everything but that still leaves the question unanswered: Why? Why does Jesus want to keep his true identity secret? What would constitute the right conditions within which his identity should be revealed?

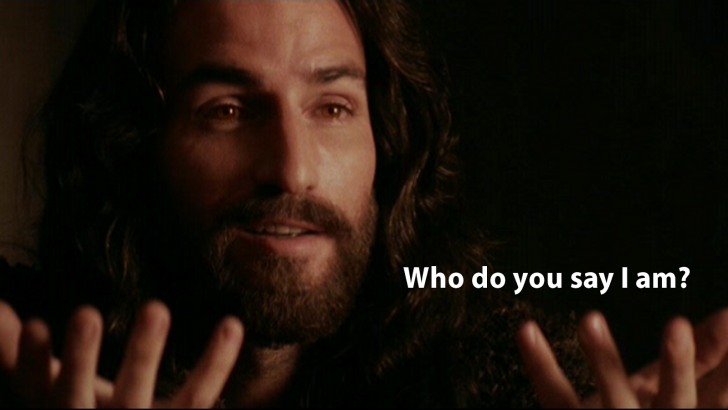

That question is centre-stage in Mark’s gospel, at Caesarea Philippi, when Jesus asks his disciples: “Who do you say that I am?” Peter answers: “You are the Christ.”

Then, in what seems like a surprising response, Jesus, rather than praising Peter for his answer, warns him sternly not to tell anyone about what he has just acknowledged. Peter seemingly has given him the right answer and yet Jesus immediately, and sternly, warns him to keep that to himself. Why?

Simply put, Peter has the right answer, but the wrong conception of that answer. He has a false notion of what means to be the Messiah.

In the centuries leading up to the birth of Jesus and among Jesus’ contemporaries there were numerous notions of what the Christ would look like.

We don’t know which notion Peter had but obviously it wasn’t the right one because Jesus immediately shuts it down. What Jesus says to Peter is not so much: “don’t tell anyone that I’m the Christ” but rather “don’t tell anyone that I am what you think the Christ should be. That’s not who I am.”

Like virtually all of his contemporaries and not unlike our own fantasies of what a saviour should look like, Peter no doubt pictured the saviour who was to come as a Superman, a superstar who would vanquish evil through a worldly triumph within which he would simply overpower everything that’s wrong by miraculous powers.

Such a saviour would not be subject to any weakness, humiliation, suffering, or death and his superiority and glory would have to be acknowledged by everyone, willing or begrudgingly. There would be no holdouts; his demonstration of power would leave no room for doubt or opposition.

He would triumph over everything and would reign in a glory such as the world conceives of glory, that is, as the ultimate winner, as the ultimate champion – the winner of the Olympic medal, the World Cup, the Super Bowl, the Academy Award, the Nobel Prize, the winner of the great trophy or accolade that definitively sets one above others.

When Peter says “you are the Christ!”, that’s how he’s thinking about it, as earthly glory, worldly triumph, as a man so powerful, strong, attractive, and invulnerable that everyone would simply have to fall at his feet. Hence Jesus’ sharp reply: “don’t tell anyone about that!”

Jesus then goes on to instruct Peter, and the rest of us, who he really is a saviour. He’s not a Superman or superstar in this world or a miracle worker who will prove his power through spectacular deeds. Who is he?

The Messiah is a dying and rising Messiah, someone who in his own life and body will demonstrate that evil is not overcome by miracles but by forgiveness, magnanimity, and nobility of soul and that these are attained not through crushing an enemy but through loving him or her more fully. And the route to this is paradoxical: the glory of the Messiah is not demonstrated by overpowering us with spectacular deeds. Rather it is demonstrated in Jesus letting himself be transformed through accepting with proper love and graciousness the unavoidable passivity, humiliation, diminishment and dying that eventually found him. That’s the dying part.

But when one dies like that or accepts any humiliation or diminishment in this way there’s always a subsequent rising to real glory, that is, to the glory of a heart so stretched and enlarged that it is now able to transform evil into good, hatred into love, bitterness into forgiveness, humiliation into glory. That’s the proper work of a Messiah.

In Matthew’s gospel this same event is recorded and this same question is asked and Peter gives the same response, but Jesus’ answer to him here is very different. In Matthew’s account, after Peter says: “you are the Christ, the Son of the Living God”, rather than warn him not to talk about it, Jesus praises Peter’s answer. Why the difference? Because Matthew recasts the scene so that, in his version, Peter does understand the Messiah correctly.

How do we imagine the Messiah? How do we imagine triumph? Imagine glory? If Jesus looked us square in the eye and asked, as he asked Peter: “how do you understand me?” Would he laud us for our answer or would he tell us: “don’t tell anyone about that!”

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

Fr Ronald Rolheiser