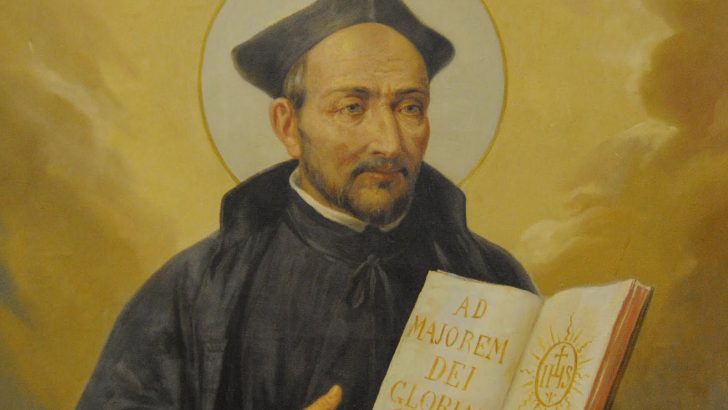

In the hallway of Clongowes Wood Castle there stands a white marble statue of St Ignatius Loyola. To the mind of at least one small boy it had a pale ghostly appearance, little suggesting a living person, and certainly not the vivid vitality of Ignatius himself.

In his book Brendan Comerford aims to reveal the man himself and to explore the relevance of his spirituality, as largely expressed through the Spiritual Exercises. My evocation of the Clongowes statue is a very Ignation device, for as that work says, el primer préambula es la historia … el second est viendo el lugar.

The notion of narrative and vision, of recreating the scenes of faith, go to the heart of what every artist and writer, even scientist, attempts through what has come to be called “composition of place”.

In the first part of his book Fr Comerford does exactly this. He places Ignatius in the context of his time, and the narrative of his life. He wishes to avoid anything of the plaster – or indeed the marble – saint. He wants to reveal the man as both his admirers and detractors (and Jesuits have always, and still have detractors – we have all heard from the time to time the very bitter things that some Catholics have to say about them).

Piousity has no place in attempting to see things as they are and to apprehend not what it is that men think ought to be done, but what God wants done.

Exposition

His concise biography fills the first part of the book. The second part, and perhaps the more relevant for today’s reader, is an exposition of Ignatius’ spirituality.

Fr Comerford has many years experience as both a teacher and a spiritual director. He knows exactly how to make what are often subtle notions clear to readers coming new to them.

Ideally his book might be read in tandem with the essays edited together by FrPatrick Carberry. He himself contributes a piece on Ignatius, but his 15 contributors write about a very varied selection of Jesuits of even more varied achievement from Francis Xavier to Teihard de Chardin. The essays are not arranged in chronological order, but rather in a thematic manner, which is in fact very revealing indeed of the Jesuit charism.

Over the centuries opponents of Jesuits saw them as some kind of papal secret service: the sinister Jesuit that haunts the imagination of Elizabethan England, the councils of France and Portugal, the yellow press of 19th Century America.

The discipline of the Jesuits derived from Ignatius’ military background, the discipline essential to carry a struggle to success, however, also demands, not a response by rote, but the ability to react as circumstances change in the flux of activity, the ability to see things as they really are.

This demands that each Jesuit contributes from his own special talents, as astronomer, engineer, philosopher, theologian and activist, or whatever. Such types are represented in the essays here, as are others of more quiet accomplishments, down even to a doorman.

Familiar names are given their place, such as Karl Rahner, the Berrigans, Vincente Cañas; but also many others less familiar.

Here too the inspiring leadership of Pedro Arrupe is discussed. But readers of all kinds – for this is a book for everyone and it would be a great pity to confine it merely to Catholic circles – have before them another example of leadership in the current Pope.

Journalists are alive to the need “to understand the Pope’s thinking”. They could do worse than look into these books for enlightenment about exactly what it is that drives the Jesuits and their work in the world. Their motto is that all things done should be for the greater glory of God.

This mission is never far from their common mind.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello St Ignatius of Loyola

St Ignatius of Loyola