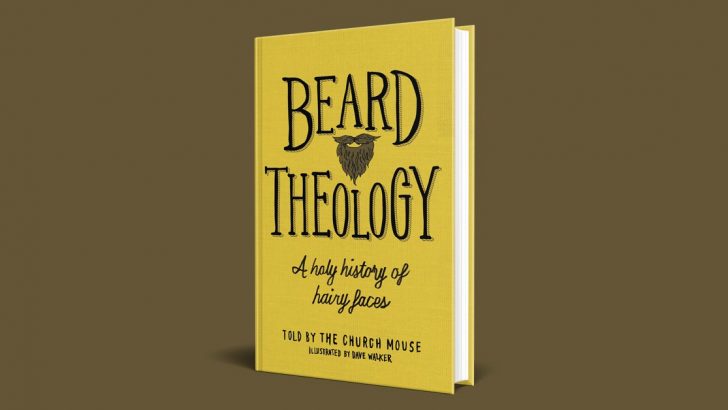

Beard Theology: A holy history of hairy faces, told by the Church Mouse

illustrated by Dave Walker (Hodder & Stoughton, £12.99)

We now live (at least in some Western countries) in an age of beards, if the five day stubble so many sport can be called beards. These unshaven faces are derided by others as mere scruffiness. Beards are and have always been important.

This little book by a well-know Anglican blogger and commentator may seem frivolous, but is in fact far from that as his text develops, dealing with a very serious matter in the history of Christianity. If people have died over this issue of facial hair, and they have, it has to be taken seriously.

What is at stake is made clear by two early quotes. St Augustine of Hippo claimed “the beard signifies the courageous, the beard distinguishes the grown man, the earnest, the active, the vigorous”. But centuries earlier St Paul had written to the new church at Rome that: “Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him” – which is curious for as images of Jesus began to circulate in the 2nd Century Jesus has been represented as a man with long hair.

This is the conflict explored in this book, specifically with the cresting views of the Orthodox Churches and Western ones, of the Reformers with Rome at the Reformation, and so on backwards and forwards over the centuries.

From these pages we quickly learn a great deal about the things that have divided Christians, foolish things it often seems to us today. We have not had a bearded Pope in some time, but there were 25 of them one after another at the time of the Reformation.

Theme

The theme followed in this book could readily be enlarged. The Victorian journalist and historian Charles McKay wrote a famous essay on the historical and political influence of beards which covered the social controversies without even alluding to religious disputes.

But these divisions are not confined to those who follow the Bible. Muslims lay great emphasis on men wearing beards as a sign of true believers; and in Asia the Sikhs do not shave or cut their hair and are deemed redoubtable warriors.

Yet in World War II and the 1950s North America thought with St Paul that long hair on a man was a disgrace, a sure sign of effeminacy. All that changed with the 1960s, but has perhaps swung back again, as America becomes once again a militarised society.

The author makes the significance of this very clear. “In its day, the issues of beard theology were considered worthy of debate alongside issues such as priestly celibacy, the nature of the sacraments and even the great debates on the divinity of Christ and the Trinity.

Beards divided not just the worldwide Church, but also the societies they represented.

“People argued about beards, taxed them, banned them and fought over them,” the author writes in conclusion.

The issues of beard theology were worthy of debate…”

“Partly this was because they believed some-thing about them. But, more importantly, it was about what beards represented. Beards were symbols of identities and social divisions that allowed people to display the difference between themselves and others in the way they looked. Identity politics has been alive and well for millennia, and beards have been part of that story.

“For those of us who consider ourselves part of the Church, there are lessons to learn about how theological differences become entwined with a sense of self and identity, which in turn allows issues to escalate in their importance. It helps us understand that we do not approach Scripture, theology or church traditions from a position of neutrality.

Such a position, in fact, has never existed.

“So beard theology is important. Anyone who wishes to live in a more peaceful world, or to learn how to understand and accept differences, must pay attention to our beard history. Those who cannot learn from their beard history are bound to regrow it.”