Medieval Philosophy (A History of Philosophy without any Gaps)

by Peter Adamson (Oxford University Press, £25)

When I discussed with a friend my intention of reviewing this tome – and tome it is, running to more than 600 closely printed pages – he wondered: “Are readers of The Irish Catholic interested in medieval philosophy?”

Ignoring this counsel of despair, I believe that a significant number of our readers are interested in medieval philosophy, and I feel they would certainly like to know more about it, its variety and its ramifications.

Many of us were brought up exposed to the view that Aquinas was the beginning and end of philosophy, for Catholics at least. But I believe, too, that many readers are interested in philosophy in general, hence the huge sales of writers such as Alain de Botton, Roger Scrutton and others.

There is a great deal of confusion about the Middle Ages. Many people have very odd notions about both the period and its thought and what they might mean to us today. This book may well be an answer to their difficulties.

Series

The author Peter Adamson, who studied at Notre Dame and King’s College in London, is Professor of late Ancient and Arabic Philosophy at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich. It is the fourth volume in a series he is writing called “a history of philosophy without any gaps”, which aims to present a complete history of philosophy more thoroughly and more enjoyably than ever before. His short, lively chapters, drawn from the materials on his popular podcast on the history of philosophy, are intended to be accessible, humorous and detailed.

Of the volumes already published, that on Islamic philosophy would seem to be of greatest value to increasing knowledge of a much distorted topic, at least in the Western media. So this series has a value beyond mere academic usefulness.

Special attention is given to female philosophers”

Let me say at once on the evidence of this volume, he succeeds brilliantly. Over some 78 sections he covers a huge range of figures, from our old Celtic friend Eriugena and predestination – a more than lively topic still today in some Christian quarters – down to Wycliffe, late scholasticism, Lull, and Petrarch.

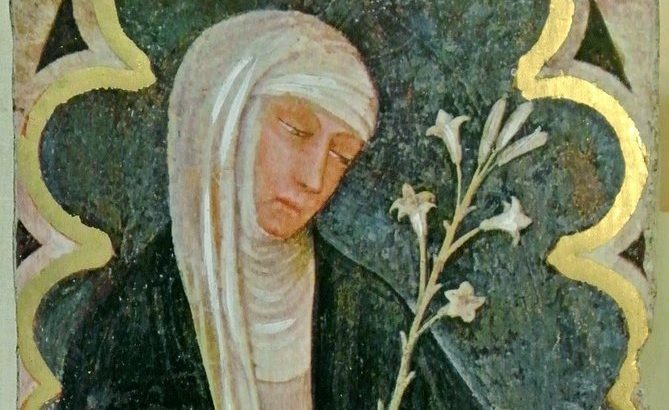

But the coverage is broader than that. Special attention is given – and rightly so – to female philosophers, such as Catherine of Siena. Such would certainly not have featured in earlier surveys of this kind. But beyond that Adamson gives space to the ideas of artists and poets, such as Dante, Langland and Chaucer, for in their works we can see the application and the illustration of philosophy as it was lived in life here on earth, and in the afterlife, as conceived by the middle ages.

The idea popular among traditionalists of the unified culture of the medieval mind – such as Chesterton and Belloc write about – is shown to be a simplification of the actuality.

When this book arrived on my desk I was puzzled by the cover which showed, not a philosopher in his study, or a theologian among his students, but a siege engine from about 1321. This seemed to suggests, to my mind, the idea that the middle ages was particularly violent (which is not so, the last few centuries with their industrialised warfare and their distanced conflicts, being the most violent ever known).

Actually the jacket shows “Christian soldiers marching as to war”, setting out to capture the stronghold of the imps and demons of ignorance and depravity.

But the cover was duly explained too by the fact that a long chapter is devoted to the development of the medieval concept of “a just war”, perhaps the most dangerous doctrine to which the name of Christianity is attached, and which has been the promoter of war, violence and death in ways not compatible with the Gospels.

From this brief survey of the contents, I hope I have been able to suggest that this book (and the others in the series), which are a delight to read, will be of great interest to general readers, aside from students of culture.

In any case, the temper of Christianity today is largely towards the more personal experience of the divine, towards ‘mindfulness’, psychology and spirituality; toward devotion untrammelled by any strictures of philosophy. Perhaps a small dose of medieval thought might well be a good thing for some. A small dose of medieval thought might well be a good thing for some.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello St Catherine of Siena

St Catherine of Siena