Martin Mansergh

The View

Following the recent acute and unseasonal cold spell, a photograph appeared on the front of the Tipperary Star showing a winter scene of the centre of Thurles, taken from the bridge over the River Suir, with the caption (anonymous): “A snowflake is one of God’s most fragile creations, but look what they can do when they stick together.”

One of the impressive features of Irish society today, taking advantage of the progress in science, technology and communication, is the ability to conduct effective crisis management in extreme weather conditions. All the resources of the State are pulled together nationally and locally by dedicated public and voluntary services, backed by the community and private initiative, especially from those who own large construction or farm vehicles.

Many no doubt wondered whether the warnings might be somewhat exaggerated. They were not, and everything possible was done in good time to make people safe. Each experience, which has tended to become more frequent, contains lessons for future reference. The relative compactness and intimacy of Irish society is a great advantage in these situations.

Justifications

One of the justifications of the nation state is the sense of belonging and solidarity it generates, which are needed on an everyday basis but are particularly vital in working through periodic crises. The office of President is important in that regard, in that it provides a symbol of national unity that transcends political loyalties.

Ireland has been fortunate in having had without exception Presidents of stature and integrity. Since the election of Mary Robinson in 1990, holders of the office have become more high profile, and exercised a certain moral leadership.

The Constitution provides the President with limited but important powers, to refer legislation to the Supreme Court for a ruling on its constitutionality before being signed into law, to refuse the dissolution of the Dáil to a Taoiseach who has lost its confidence, and the right to make significant public statements, provided they are free of political partisanship. State visits provide important opportunities to cement relations with other countries.

The President serves for seven years, a term which can be renewed once. Re-election can of course be contested, but may not be, if there is no perceived public appetite for change. Presidential elections are expensive not just for parties, but for the contestants, and often a bruising experience. The personality of candidates is subjected to close scrutiny, as the scope for policy promises is limited. An incumbent President who is above politics may find it difficult to step down into the electoral arena again.

No one can seriously suggest that President Mary McAleese, when she greeted Queen Elizabeth II in 2011 towards the end of her second term, lacked a mandate, just because her re-election was not contested. As is the case in most other democracies, the successful candidate should ideally be someone with substantial experience of politics or administration or some other representative role.

Just as President McAleese was the right person for the bridge-building role required by the peace process, President Michael D. Higgins has up till now been the right person to participate actively and creatively in the decade of centenaries and to set the appropriate tone of empathy, critical appreciation and understanding. Inevitably, choices have to be made, and each President has to be allowed a measure of discretion as to how they exercise that role.

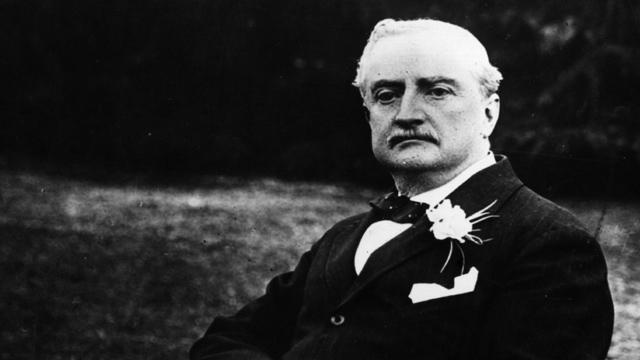

The anniversary of the moment is the death of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) leader John Redmond, who died 100 years ago on March 6, 1918, and who still arouses controversy.

It ought to be possible 100 years on to transcend the raw partisan divisions of that time, and to accept that the construction of the Ireland we have today, not all good of course, was contributed to by different hands over generations, even if particular gratitude is owed to those who finally brought independence to fruition.

John Redmond was once practically a taboo subject in Irish history. That has been much repaired in recent times, with a two-volume biography by Dermot Meleady and now the just published volume in the fine Royal Academy series Judging Redmond & Carson by Alvin Jackson. The problem is that many of Redmond’s eulogists and detractors exaggerate their case.

The positive achievements should not be ignored. Redmond reunited the IPP in 1900 after the disastrous Parnell split, and made it again a force to be reckoned with, leading it for the next 18 years in tandem with John Dillon.

The period from 1898 to 1911 saw the introduction of lasting and substantial reforms, the introduction of democratic local government, the transfer of land ownership to former tenants following the Wyndham Act and further legislation in 1909, and the establishment of the National University of Ireland, which had the support of the Catholic Church. The curtailment of the House of Lords veto with IPP support opened the way to a realistic possibility of self-government.

There were some negatives, like opposition to women’s suffrage or to State inspection of church-run institutions, and reservations about the old-age pension, not shared by its recipients.

Above all, with close attention by Irish MPs to constituency issues, to the frustration of the Imperial Parliament, the IPP helped accustom the people to participation in a parliamentary democracy, so that after the independence struggle it was the norm to be returned to.

There can be little doubt that the quid pro quo for putting Home Rule on the statute book in September 1914 even if suspended, in the face of stiff unionist resistance, which at least made it a benchmark, was Redmond’s encouragement to young Irishmen to join up following the start of the First World War.

Given the prolonged impasse in implementation, a minority who always wanted full independence saw a unique opportunity in the war to stake that claim, counter the embrace of British imperialism, and go well beyond Home Rule. Yet, when things settled down again, the continuities were as significant as the breaks.

John Redmond

John Redmond