The Belfast-born poet Derek Mahon, who died last week, aged 78, after a short illness, was rightly acclaimed as one of the finest poets of our time.

I knew Derek (along with his late wife Doreen) as a friend and a neighbour – when our children were young they played together in London’s Kensington. The kids all have happy memories of those times. I would later meet up with Derek in Dublin – he had a perch in the tea-room of the Shelbourne Hotel – and in West Cork, where he finally settled.

And it was in Kinsale, West Cork that Derek Mahon probably saved my life. As well, quite possibly, as the lives of others.

Story

It is a shameful story – shameful on my part, heroic on his. After an evening’s revelry in Kinsale – this would have been back in the 1980s – I staggered towards my hired car to drive back to the hotel.

This really was a deplorable scene. After an evening’s imbibing of alcohol, I was massively over the legal limit. I was sozzled, legless, paralytic, to use the vernaculars. I could hardly find the gear-stick.

Derek opened the door of the vehicle and said: “No, Mary, you mustn’t! Stop!”

My mother always used to say that “you cannot reason with a drunk”, and so it proved. I insisted I could drive. I told him to get lost, stop ordering me about, stop being a male chauvinist, I was an independent person – all the usual drivel that drunks blather.

It’s not that reason disappears with drunkenness – it’s that it becomes totally distorted.

Then Derek acted. He reached into the vehicle and switched it off, taking away the ignition key. Yes, he took away my ‘autonomy’, and rightly so. “You can’t drive, Mary, and that’s an end to it!” He then called me a taxi.

The next morning, overcome with remorse, I rang to thank him. I could have killed myself by driving in such an extreme state of inebriation. Worse, I could have killed, or harmed, others.

Derek understood and was subsequently forgiving of the episode. He had been there himself – he, too, had wrestled with a serious alcohol problem. He had quit and got sober, but he had an insight into the madness of inebriation.

Good deed

Not long after that, I followed Derek’s lead. I found my way to sobriety, and have, thankfully, remained sober.

Derek was not a believer – although he grew up in a strict Protestant family – but his decisively good deed was surely an act of grace.

Later, he did give me the recipe, over coffee at the Shelbourne, for a non-alcoholic ‘high’, if the need for a boost was overpowering. This was: two double expressos, washed down with a Coca-Cola. The caffeine ‘hit’ is indeed something! But you’d want to make sure your heart is in full, robust condition.

I lift a coffee in homage to you, Derek, in the spiritual afterlife.

Can’t beat the human touch

Before all the museums and art galleries sadly closed down in Dublin, I was fortunate enough to see a most rewarding exhibition about St Kevin and Glendalough at the National Museum of Ireland in Kildare Street.

It is stunning what can be done with modern lighting, and computer-generated images, rendered through three dimensions and photographed, as it were, from the air. This exquisite part of Co. Wicklow, in all its rich archeological glory is wonderfully illuminated.

However, I would have liked a little more human ‘narrative’ about St Kevin (Caoimhín, or Caoimghín), who died in AD 618. His family story is recorded in O’Riain’s authoritative dictionary of Irish saints. He came from a dominant dynasty in Co. Wicklow – and in these Irish traditions, the mother’s family was as worthy of note as the father’s.

Computer-generated images are fabulous, but the curators of exhibitions shouldn’t omit the human stories associated with a great pilgrimage site. Hopefully, when present conditions change, the Glendalough show will still be there.

***

Derek Mahon’s poetry was translated into French by a French poet, Philippe Jaccotet (and in turn, Mahon translated Jaccottet’s work into English).

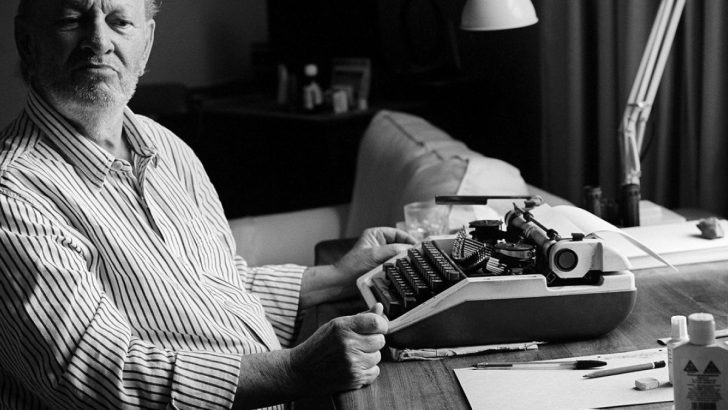

Jaccottet asked about the cultural and political context of Northern Ireland and so, Derek [pictured] started to explain it to him. “There are Catholics, and there are Protestants,” he said. “And politically, there are Republicans and there are Loyalists – they consider themselves Loyal to the Crown.”

Jaccotet took this in, and then concluded: “And naturally, the Protestants are Republicans, and the Catholics are Royalists, yes?”

Well, no! Derek had to explain that it didn’t work like that in Ireland.

The Frenchman was drawing on French history, where one of the most ardently Catholic parts of France – the Vendée – had been the most fiercely monarchist. ‘Crown and altar’ had been linked together elsewhere, too, as in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

European history is complex. The patterns aren’t the same everywhere.

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny Derek Mahon

Derek Mahon