Joyce the Student: University College 1898-1902, Dublin

by John Kelly (Gleoiteog Press, €15.50/£12.99)

During June an air of Joycean enthusiasm descends on Dublin, with all kinds of events — and even non-events in the eyes of some — taking place. This year, however, a local writer makes a real contribution by the publication of a book, one devoted to Joyce at University College Dublin, in the days when it was a Jesuit institution, small and struggling.

John Kelly, it will be recalled, mounted a protest that carried the day when the university authorities announced, in keeping with some notion of secularity, they would not be represented at the canonisation ceremonies of their founder St John Henry Newman in October 2019. This had seemed even to the many who are not graduates of UCD, to be a curious lack of both respect and courtesy. Cardinal Newman’s own exemplary good manners now seem a relic of a forgotten era.

Career

Aside from his own distinguished career, John Kelly, was for many years the college registrar, and is associated with families associated with the old college as well as the new university. He has a deep feeling, a pious memory such as the Romans cherished, about its past.

The present book springs from this same feeling, for by metier he is a chemical engineer, but his university days were partly spent in those old buildings around St Stephen’s Green, that had been the haunt of Joyce himself back in the first days of the 20th century.

Dr Kelly is not the first to write about this period, so he has a deep well of books to draw from.

But this book is aimed at the general reader, the person, perhaps a student at Belfield indeed, who wants to know something about Joyce, but does not want to drown in too much detail (drowning in details are the very stuff of Joycean discourse).

In his pages John Kelly provides a résumé of Joyce’s UCD connections, including a very useful anthology of what he wrote as student during these years. These essays, in their maturity and determination, will surprise many who only know the later literary Joyce.

All in all though the education and intellectual training he received from the Jesuits is emphasised. Joyce admired Newman too, so that his mind as a young man was pervaded by scholastism. In fact Newman is a part of this book as much as Joyce.

Familiar

Joyceans may feel the contents are familiar, and so they may be, to Joyceans. But not all books about Joyce are intended for the Joycean. John Kelly wisely has chosen to write for that far larger group of those who are interested in Joyce and would like to know more, but cannot face the serried ranks of shelves that contains all that has been published by and about Joyce.

There are places, however, where one feels he could have said more. Writing about the faculty of the college appointed by Newman and the need for research he overlooks Eugene O’Curry as professor of Celtic Archaeology. His lectures, later published, are one of the intellectual monuments of Newman’s time. Prof. O’Curry, as far as I can work out, seems to have been the first such professorship of archaeology ever. His work transferred the study of Ireland’s past onto a more scientific basis, as did that of John O’Donovan. When published their lectures were recognised as monuments of scholarship and research.

In Joyce’s time things were worse. The college had no real library – Prof. O’Curry and Prof. O’Donovan had used the resources of the RIA. The students were accustomed to use the National Library – where indeed some scenes in Joyce’s work are set.

But already these comments are moving into the sort of detail that bewilders many. John Kelly keeps on the level, and rightly so.

This will be a book which will enlighten many, especially those who have both Newman and Joyce in their minds, but it will also suggest to others more deeply engaged with Joyce new lines of investigation.

Peter Costello

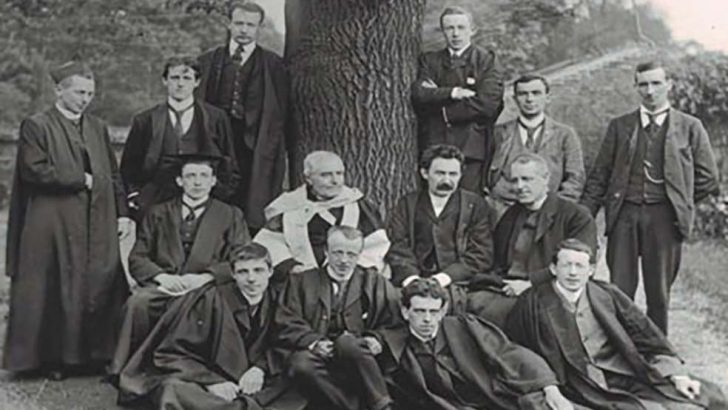

Peter Costello James Joyce (second from left) among a college group at UCD. Courtesy UCD Archives

James Joyce (second from left) among a college group at UCD. Courtesy UCD Archives