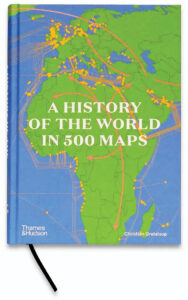

A History of the World in 500 Maps, Christian Grataloup and others (Thames & Hudson, £35.00/ €40.50)

This is an interesting and unusual book. It was originally published in French a couple of years ago. Christian Grataloup is the overall editor; the introduction is by Patrick Boucheron; other associates were French academics; and the attractive cartography is also by French experts.

The whole project thus breaks free of the Anglo-American centred worldview which we in Ireland have all too often to make do with, in favour of a more European centric one. This is a value not to be underestimated these days.

The team who put it together wanted to create what Mr Boucheron calls “an atlas for the 21st Century”, and that is indeed what they have created between them.

Though the present century weighs heavily on us all, with so many problems derived from the failed and even successful politics of the past two centuries, this book vividly illustrates and illuminates the environmental context in which the past took place and with which the rulers of today and indeed the ordinary people struggle as events in Amazonia, and indeed only the other day in Maui, ordinary people struggle often on their own. We need maps to understand it all.

There are a few things I would have liked to see, but let’s deal first with the positive points.

First as to size. Unlike too many atlases this one is a handy size for family, school or college use. These days a sensible size is important.

But it is also an atlas, it shows history through maps. This too is not to be undervalued, even though many people, even many historians, seem to have little understanding of what maps can reveal: this is the result of poor teaching at school and early college levels.

A good half of the nearly 600 pages is devoted to the world since 1492, a third to the world since 1914. This may seem unbalanced, and yet it is not: the earliest pages certainly illustrate many aspects of ancient and medieval history to which we give little attention, the major developments in China and India for instance, which are essential for understanding the aspiration and claims to status and respect of India and China today.

Coming to more modern times it may be a surprise to some to find a whole page graphically devoted to Lenin’s train journey in 1918 under the auspices of the German Empire that took him from exiles in Zurich to the Finland Station in Petersburg, so he could meddle with the democratic revolution which had already broken out. The consequences of that sealed carriage are still with us to this day, despite the fall of communism, in the attitudes of President Putin.

But the heavy attention to the recent past will be what makes this book attractive to many younger users, for they illustrate so many events and movements which the cultural isolation of the very recent decades has inured so many. Here a series of maps will help illuminate, for instance, the continuing turmoil of Africa.

The interests of those concerned with religious matters are also served, for the rise, spread, and fracturing of Christianity all receive detailed treatment, as do the intricacies attending the origins and global spread of Islam.

For many people under 30, this book will prove to be as good as a new education. They will really learn about the world in ways they have never seen before.

This is a book which can be warmly recommended to the ordinary reader. It is remarkably good value, as the prices of some academic books from university presses go these days. Indeed, for all the expertly distilled and strikingly presented information that it contains, it is wonderfully cheap.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello