Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion

by Andrew Robinson

(Thames and Hudson, €14.99/£12.99)

People often remark carelessly on what the sacred writings of the Bible and the New Testament “say”. They give little thought, as often as not, to the astonishing ability of being able to read a text in translation from a language they cannot understand, but which thanks to scholars and translators comes to them as if they were the actual words of Moses or Jesus (or any other great religious figure). This is really not something we should take for granted.

In the Middle Ages, say from about 450 to 1450, Greek, Hebrew and even Latin were not as well known in Europe as we sometimes think. But then few people could read even their own language.

The writings of ancient Egypt were even more difficult. They could not be read at all. People guessed at what they might say, people like the extraordinary Jesuit scholar Fr Athanasius Kircher. This led to strange assumptions about ancient Egypt, about the magical power of its language and the hieroglyphic writing, just as bitumen from ancient mummies was credited with strange properties and was traded all over Europe, ground up finely in medical potions.

However, at last the language code was broken and the mystery was dispersed. We could hear the ancients in their own words. There were other breakthroughs too. Not only the Rosetta stone, but the Rock face at Behistun, and others, followed after careful comparison and parsing.

In this book Andrew Robinson gives a highly readable account of how the code of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing was broken. Champollion is indeed the chief person involved, the person from whom the modern stream of translation comes, but many others were involved and made their contributions to.

Heroic break-through

We love the idea of the heroic break-through by a single solitary genius, but forget that often important discoveries come to the minds of many at the same time: their hour has simply come. These others, in several countries, who were involved, aside from Champollion, should not be forgotten.

However, once made a translation very often came to dominate. The King James Version is nearly always used by journalists, the NIV by scholars. I myself like to use the Douai-Rheims version for all contexts earlier than 1450, and certainly all Catholic contexts down to 1900. I suppose having been reared on it, it sounds more truly medieval, the King James Version to my mind belonging to the Enlightenment.

Anyone fascinated by the mysterious ways of translation, and their effect on the course of culture, will delight in this book, but the whole story is much more complicated than the triumph of one genius.

Peter Costello

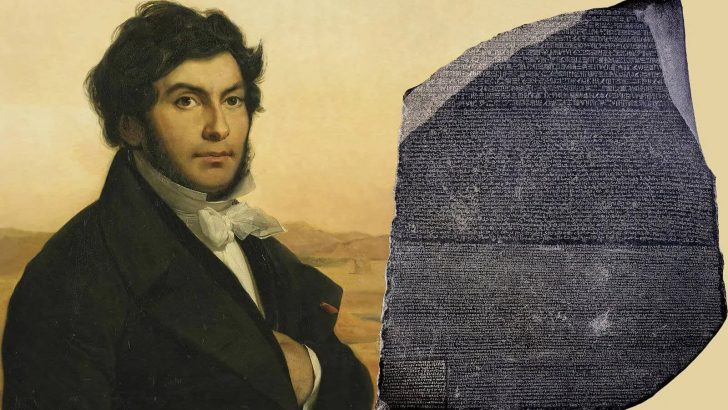

Peter Costello Jean-François Champollion and the Rosetta Stone which aided in the decoding of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Jean-François Champollion and the Rosetta Stone which aided in the decoding of Egyptian hieroglyphs.