The Vatican is under increasing pressure to take a stronger line with Beijing, writes Jason Osborne

Recent footage documenting blindfolded, handcuffed, and shaven-headed people being detained and loaded onto a train in the Xinjiang region of northern China has seen the international spotlight slowly turning in China’s direction.

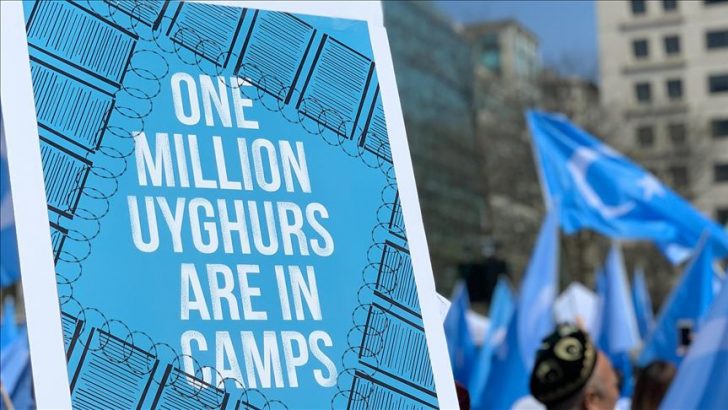

What China is being accused of is the persecution of its Uyghur Muslim population. Currently, this persecution is primarily taking the form of internment of upwards of one million people in camps, which the Chinese government refer to as ‘re-educational camps’ and ‘vocational schools’.

On top of this is the ongoing demolition of mosques and bulldozing of cemeteries across both northern and western China. Under increased scrutiny and facing demands for explanation from a number of governments and human rights groups, China has reaffirmed that its measures are all in accordance with the rule of law, citing the threats of terrorism, religious extremism, and political dissent as impetus for these actions.

Tension

While the heat is only tentatively being applied to China now, the tension between China and its minority Uyghur population of 11 million, mainly in Xinjiang province, has been boiling for some time now. Uyghurs are a mostly Muslim Turkic ethnicity, culturally as close to the middle east as they are to Beijing.

In the early 20th Century, Uyghurs briefly declared their independence, but the Chinese Communist Party brought this to a comprehensive end by 1949, and so it has remained until today. Xinjiang is technically an autonomous province within China, but in reality, it is governed totally by the Chinese state.

Identify

Over the past decades, an attempt has been made by the Chinese government to bring Xinjiang into deeper alignment with the main body of China, and this has resulted in the curtailment of the Uyghur’s religious and cultural identity across the province, as well as an influx of Han Chinese to the area. In 1990, riots sparked in a small corner of Xinjiang, and again in 2008 as the Beijing Olympics approached. In 2013 and 2014, Tiananmen Square and the Chinese city of Kunming were subject to attacks carried out by Uyghurs that stoked further unrest, and gave the Chinese government clearance to begin a surveillance operation in Xinjiang province the likes of which has never been conducted before.

Technology is heavily involved in this effort, and sees facial recognition cameras, mobile phone monitoring devices, and the collection of biometric data used against the inhabitants of the region.

China has long denied internment camps, only recently admitting to the existence of the aforementioned ‘re-educational camps’ and ‘vocational schools’. They insist that these are in response to the threat of extremist violence that Uyghur militants pose, and that the aim is of these ‘schools’ is to ‘encourage students to truly transform’, according to a nine-page memo sent out by Zhu Hailun in 2017, then deputy-secretary of the Communist Party and the Xinjiang region’s top security official, to those who run the camps.

Churches are closed, the sale of the Bible online banned, crosses and crucifixes removed, priests and worshipers arrested”

This rehabilitative image has come under greater duress in recent years, with scraps of footage, leaks and the testimony of escapees reinforcing the suspicion that China is detaining at least one million Uyghur Muslims outside of the due process of the law.

Beyond this, it is now understood that prisoners are subject to indoctrination, humiliation, and torture. Recent reports also highlight a programme of forced sterilisation for Uyghur women, as part of a suspected campaign to curb the birth rate among the Uyghur population, even as the country’s Han Chinese population are encouraged to have more children. Forced abortions and intrauterine devices (IUDs) are commonplace alongside these measures.

Effort

While this apparent effort to homogenise a people is weighing most heavily on the Uyghur population, it is not limited to them. China’s crackdowns have seen other religions and their adherents suffer too, with Christians subject to various methods of discrimination and persecution.

Churches are closed, the sale of the Bible online banned, crosses and crucifixes removed, priests and worshipers arrested, and homilies monitored, to ensure they’re sufficiently in line with Communist Party values and policy.

The treatment of Catholics, along with the rest of the religious faithful in China, has seen many turn to the Vatican, demanding a stronger response. Foremost among these has been Lord Patten, former governor of Hong Kong and former media advisor to the Vatican, who claims that the Vatican “has got it badly wrong about China”. Speaking to The Tablet in Dublin, he mentioned that the Vatican’s attempts to normalise a relationship with China in the current climate were “bizarre”.

Lord Patten is not alone in voicing these concerns, but is joined by the retired Bishop of Hong Kong, Joseph Cardinal Zen, who, in an open letter to Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, warned against entering into negotiations with a communist regime, after the example of Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI.

He quoted Pope Benedict in conversation with journalist Peter Seewald, in which he said of communism: “instead of being conciliatory and accepting compromises, it was necessary to resist it forcefully”.

The Sino-Vatican deal of 2018 saw cooperation between Rome and Beijing regarding the appointment of Chinese bishops. Despite this agreement, there is little, if any, evidence two years later that China’s Catholics are any freer, and the opponents of the deal question whether entering into dialogue with a regime imprisoning over a million Uyghur Muslims while repressing the Faith of millions more, is a thing worth celebrating.

Photo: Anadolu Agency

Photo: Anadolu Agency