Living With The Gods: On Beliefs and Peoples

by Neil MacGregor (Allen Lane, £30)

Patrick Claffey

Neil MacGregor, the distinguished British art historian and museum director, is currently the creator of the Humboldt Forum, a new centre for world culture in Berlin. Many will have seen exhibitions or read his books, including A History of the World in 100 Objects. As a Catholic he brings a new and different perspective to the role and uses of art and its inherent meaning for us all.

In this, his latest publication, He immediate sets out clearly what the book, based on an impressive exhibition and television documentary he created, is all about. His ideas will certainly enlarge the views of many about religion as a phenomenon.

‘[It]is about one of the central facts of human existence: that every known human society shares a set of beliefs and assumptions – a faith, an ideology, a religion – that goes far beyond the life of the individual and is an essential part of a shared identity.’

He has an obvious respect for faith, but he is not blind to the problems. “Such beliefs,” he writes, “have a unique power to define – and to divide – peoples.”

He places the emphasis on faith stories. “The most powerful and most sustaining of any society’s stories are the work of generations. They are repeated, adapted and transmitted, absorbed into everyday life…”

Stories are one of the foundation stones of belief.

The author’s interest is in religion “as practice rather than doctrine”. This is the world in which people worship together, or quietly say their daily prayers, in the belief that they are being seen by but also catching glimpses of some ultimate reality, however they name it.

The book is divided in six sections. In the first, the author looks at “stories from four continents told by communities to articulate their own understanding of the cosmos and their place in it”.

In ‘Believing Together’, he examines how “the transient existence of each single life is woven into the much longer time-span of the community as a whole – how one life meshes many across the generations”.

Community

It’s not simply a matter of believing but perhaps more importantly, of belonging to a community. Here ritual sees us through life with its “great disruptions of birth and death”. As a religious sceptic friend remarked at his father’s Catholic funeral: “Hmm, they certainly do this better than anyone else.”

In ‘Theatres of Faith’, he observes: “In sacred buildings and in ritual acts…societies articulate a view of the proper meaning of the world”. These are an important source of belief and social cohesion. Seamus Heaney caught this beautifully when he wrote of an Easter Vigil gathering as “elbow to elbow, glad to be kneeling next / To each other…”

The faith of many traditional Irish Catholics often has a close relationship with ‘holy pictures’ and other religious objects, the Virgin Mary, the Infant of Prague, St Anthony and St Jude. In ‘The Power of Images’, MacGregor tells us that man-made religious images create “a sense of shared belonging” and can “carry us into worlds beyond words and beyond ourselves, worlds normally accessible only to poets and prophets, mystics and shamans”.

Even in our secular age, an image or votive statue discreetly left by granny will not be discarded, but kept discreetly and referred to in a time of crisis. Equally, “stepping into the church to light a candle and say a prayer for a special intention” even when one rarely advances much further than the statue of St Anthony near the front door.

As the author states in his penultimate section, ‘One God or Many’, one key questions today is “how to live not only with your own gods, but with the gods of others”. It is certainly true that many of the major conflicts in the world today are framed in religious terms, even if their real causes are worldly.

The question he poses in the final section, ‘Powers Earthly and Divine’ is certainly one of the great questions of our time, when religion is often treated as a threat to social cohesion. And this at a time when many religious people see themselves as a persecuted minority.

“How,” MacGregor asks, “do communities of faith flourish in societies inevitably run by politicians. Religious teachings can underpin the authority of ruler but can also be used to hold them to account. Strengthening the nation-state by imposing a national faith – or even a national atheism – has always had a great appeal, but also brought great problems. In spite of all difficulties, the dream of a heavenly city, somehow to be achieved on earth still endures.”

Peter Costello

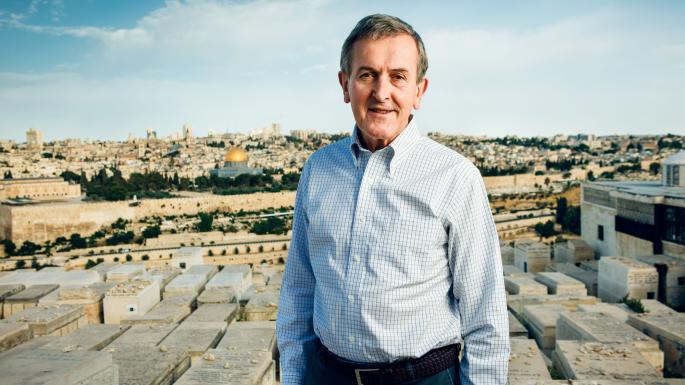

Peter Costello Neil MacGregor in the Jewish cemetary overlooking Jerusalem

Neil MacGregor in the Jewish cemetary overlooking Jerusalem