“To say that he suffered from a ‘mental illness’ is to suggest that people with a mental illness are inclined to be psychopathic killers”, writes Mary Kenny

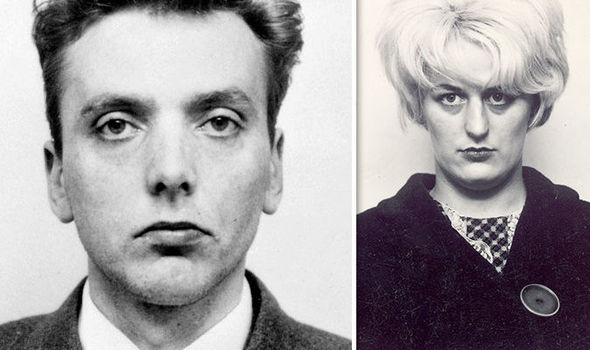

I’ll never forget Michael Parkinson, the television host, telling me about his experiences as a young reporter in the north of England during 1966, when he was sent to cover the trial of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, the Moors murderers.

The press gallery, he said, was packed with experienced and even hard-bitten crime reporters who had seen every type of crime. But when the tapes recording the tormented screams of the murdered children were played in court, everyone was seen in tears. It was, recalled Mike, the most unbearable experience of his life.

There was widespread public regret that the death penalty had just been abolished, so Brady and Hindley were sentenced to life imprisonment for the five children they had murdered, several of whom had also been sexually assaulted.

Later, in prison, Myra Hindley said that she felt she should have been hanged. Brady, who was judged to be the more culpable of the two, and who has just died of natural causes aged 79, requested assisted suicide since 1999 – refused on grounds of mental health.

Hindley, perhaps under the influence of Lord Longford, an indefatigable prison visitor, expressed remorse. Brady did not, and went to his death refusing to say where one of his little victims, was buried.

The Ian Brady case (Brady was the name of his Irish stepfather – he was born Ian Stewart) has evinced much speculation on the nature of wickedness: and whether he was ‘bad or mad’. His lawyer Robin Makin has claimed that Brady suffered from a “mental illness”, but the popular press, and popular opinion too, simply regards him as evil.

If so, where does such evil come from? Was he born that way or did something in his disjointed childhood cause it?

To say that he suffered from a ‘mental illness’ is to suggest that people with a mental illness are inclined to be psychopathic killers. To say that it was caused by a dysfunctional childhood – he was born illegitimate – is to diminish the many heroic people who have overcome hard childhoods. To say he was born evil is to say there is no redemption from a pre-destined fate.

Gallows

Saved from the gallows by parliament, Brady lived 50 years behind bars and in solitary confinement (to protect him from attacks by other prisoners), and in all that time no answers really emerged as to why he carried out these terrible deeds, which haunted the victims’ family ever since.

His life is certainly an example of the moral, philosophical, but very real, problem of evil.

Macron true to Jesuits

The French economist Alain Minc – one of President Macron’s mentors – has told the Irish journalist Melanie McDonagh that M. Macron is “a liberal Catholic”. Well, he is a Jesuit boy, and it would be surprising if a Jesuit education hadn’t left a formative mark. And he does seem to be less fanatically secularist than some elements in French republican tradition.

McEwan’s novel approach is risky

The Scottish novelist Ian McEwan has annoyed many older British people by suggesting that if a new Brexit vote were to be held in 2019, thankfully, many oldies will have died off. “2.5 million over 18-year-olds freshly enfranchised [in 2017]. 1.5 oldsters, mostly Brexiteers, freshly in their graves.”

Novelists, I’d suggest, seldom make astute political or social commentators.

They excel in writing fiction – that is to say, making things up. In the Irish context, I rarely find that Marian Keyes or Eimear McBride are towering intellects of political thought.

McEwan’s commentary on oldsters falls into the Stalin’s Error category. Stalin famously said that religion would fade away in Russia because “only old people are seen in church”. He failed to consider that anyone who survives into old age – admittedly a challenge in Stalin’s Soviet Union – eventually becomes old. He also failed to understand that faith was deeply embedded in the Russian people, and it would spring forth once again in the exquisitely rebuilt onion domes visible today.

It’s possible that Brexit politics may have changed by 2019. It’s possible that the British people might vote differently. But anticipating the dying-off of a cohort of people doesn’t usually turn out just as predicted. ‘Be surprised by life’ is the wisest counsel!

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny Ian Brady and Myra Hindley

Ian Brady and Myra Hindley