The Hell Fire Club, Dublin’s Dance with the Devil,

by Maurice Curtis

(The Old Dublin Press, €20.00 hb)

Sléithe Séadchomartha Bhaile Átha Cliath,

Sharon Greene & Noel Jackman, designed by Sara Nyland,

An Siopa Leabah, 6 Harcourt Street, Dublin 2, D02 VH98; free of charge (but packing and postage extra)

When I was a child the area around the so-called “Hell Fire Club” and the Massy Estate was the destination for outings on many long summer evenings, such as we have been having of late.

Equipped with a large thermos flask of tea and frying pan we would drive up into the hills, and light a little fire to cook sausages, eat home buttered slices of bread and drink tea as an alfresco supper while enjoying the scenery.

(We took care, of course, to rub out the fire before leaving. Nowadays with our much drier climate lighting fires in wild places might better be avoided.)

Accounts

Like all Dubliners I heard accounts about the ‘bad things’ supposedly done there, but they were never really clear in my mind. Later I spent too much time with the sort of experts who always refer to that grey grim ruin as “Speaker Connolly’s Lodge” and never by its folklore nickname to really believe the legends.

In this pleasantly amusing new book from local Dublin historian Maurice Curtis, that rim grey ruin, despite the title, plays only a small part to play, for the theme of the book is basically the low haunts of the city itself and the grandees of politics and literature who resorted to them.

For some perverse reason Dubliners delight in aspects of their city’s squalid history. There is little here of the quiet and respectable lives of ordinary people (the sort of people celebrated in the late Tony Farmer’s classic book Ordinary Lives) They have always been there and are the real story of Dublin.

Yet readers, it seems, prefer to read of disorderly lives, though in reality such things have always played only a small part in the making of society. But Maurice Curtis’s book is still, in its colourful way, very entertaining.

*

Turning to the second title, after so much about the sordid side of city life, proves to be quite a breath of fresh mountain air.

This small book was supported by South Dublin County Council, DLR council, Dublin Mountain Partnership and others, such as Abarta Heritage, and despite its original cost, it is now being given away free (yes, free) by the Irish language book shop in Harcourt Street.

One of the first images in it is a view from one of the window openings of the Hell Fire Club, overlooking the city below, its concrete spread coming ever close to the mountains like a dreadful lava flow since the lodge was built.

Of course, the lodge features in these pages, but it is just the thing for any family keen on exploring, providing as it does a wonderful overview of just what can be found and seen in those hills spreading away to the south to the Wicklow Border.

Vague

Irish people often seem to have a very vague idea of the past, “the olden days” as some still say. But the timeline here is a long one, running from the first signs of humans in the Mesolithic about 8000 BC, though the Neolithic farmers, the Bronze and Iron Age, the coming of Christianity, the Viking and medieval invaders, and so to modern times, and the first efforts at industrialisation.

This is some ten thousand years in all: the olden days indeed. I was very taken by an image of the cross at Rath Michael, dating from the 12th century, mounted on a boulder, around the base of which are grouped small stones left as tokens by those in the recent past who visited it and prayed there. You can almost feel on the page the living past, for though the industries have died, the faith that erected this monolith still lingers on.

The relics of the past include prehistoric monuments up to recent times, all supported by some very fine photographs, maps and charts. I have some regrets, as every ecologist, has about the baleful armies of pine trees that the state forestry body always thinks of planting – they grow fast, bringing a quick return on the invested tax payers’ money. But they are unpleasant places in reality, nothing like a genuine forest, and not as good for wildlife as many people suppose.

But this book is the sort of thing that every family driver should have to help them plan expeditions on foot, bike, or if need be, by car, to add a sense of wonder to those family summer evening drives.

Peter Costello

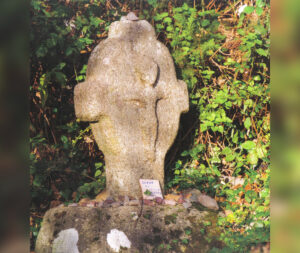

Peter Costello The “Hell Fire Club” on a summer evening.

The “Hell Fire Club” on a summer evening.