After Jean Vanier, how can L’Arche go forward creating places of belonging for those whom society rejects, asks Dr Liam Waldron

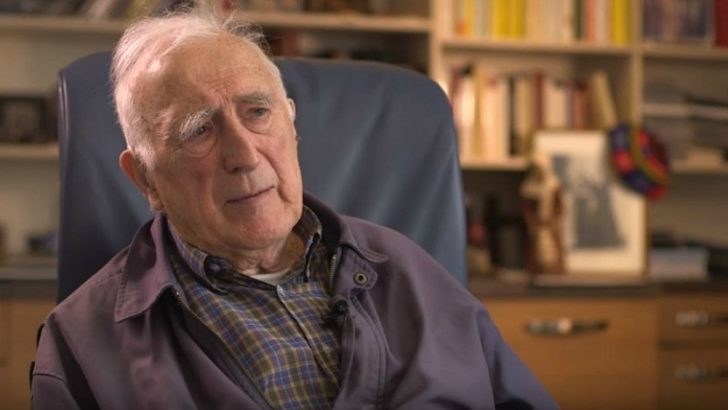

In a YouTube video recorded in 2018 to celebrate his 90th birthday, Jean Vanier, the founder of and inspiration for the international network of over 150 intentional communities, known as L’Arche, spoke about his ‘ten rules for life’.

In reminding us that one day we must all die, he says: “I’m not the one who’s the king of the world and I’m certainly not God. I’m just somebody who was born 90 years ago and will die in a few years’ time and then everybody will have forgotten me”.

Until recently, Jean Vanier, who died in 2019, was likely to be remembered chiefly as the inspirational figure who taught us how to love our brothers and sisters with disabilities. Sadly, we now have another reason to remember him with the news reported by L’Arche International that, “on the balance of probabilities”, Jean Vanier had abusive relationships with a number of women “under conditions of psychological hold”, relationships which broke “the bond of trust expected of those providing spiritual accompaniment to others”.

These revelations have been met with disbelief and great sadness and have caused much pain to those who regarded Jean Vanier as a ‘living saint’.

Loneliness

I heard Jean Vanier speak twice while carrying out research for my PhD dissertation which was a theological study of the problem of loneliness among people with learning (or intellectual) disabilities.

On both occasions, I listened spellbound to his insights on belonging and brokenness and loving friendship, delivered as they were in his characteristically soft and calming tones. If theologians have heroes, and they frequently do (often other theologians!), then I had found mine.

At the second conference, I approached him and he gave me 15 minutes of his valuable time. I asked him how people who appeared to have differing starting points for conversations about disability could find common ground. While some use primarily the language of personal rights and equality and inclusion, others use the language of vulnerability, and brokenness and fragility, which was Mr Vanier’s own language. For some, success was to be found in overcoming the limitations that disability imposes on us, while for others, Mr Vanier included, people are beautiful the way they are.

Did he think these were mutually exclusive positions? How could they be reconciled given Mr Vanier’s insistence that all human persons, with or without a disability are fragile and vulnerable, language many dislike in the context of disability? It was an inspiring conversation, full of warmth and of hope, for which I am grateful.

Given then the recent evidence that Jean Vanier acted contrary to the values of the organisation he founded, how can L’Arche go forward with confidence in living its mission of creating places of belonging for those whom society rejects? It would be tragic if L’Arche, which now mourns the death of a particular image of its founder, were to lose courage. In her book, Gateway to Hope: An Exploration of Failure, Sr Maria Boulding writes that “at the heart of our bitterest experience of failure, there is an open doorway to the joy of God”.

Opportunity

L’Arche has the opportunity now to enter through this open this door and enter into a new phase of witnessing to the importance of every human person.

L’Arche is a worldwide federation of intentional Faith-based communities where people with intellectual disabilities (the core members) and assistants share their lives through living and working and celebrating together.

The organisation, which now has a presence throughout the world, began in a small house north of Paris in 1964 when Jean Vanier invited Raphael Simi and Philippe Seux, two men with intellectual disabilities, to leave the grim hospital where they had been placed to come and live with him. The three men did everything together – worked, laughed and celebrated life.

The core members and assistants in L’Arche today do just that, and they are a living sign to the world that a life worth living does not require us to be successful in the widely accepted meaning of the word, but rather involves the embracing of our own fragility and vulnerability which is what leads us to become more fully human, echoing the title of one of Mr Vanier’s books. L’Arche could be said to be an example of what the theologian Werner Jeanrond calls, “an institution of love”.

****

Love must be at the heart of all relationships for a Christian, and institutions of love, which can include clubs, associations, churches, parishes and all manner of partnerships, are places where love is practiced according to the traditions or priorities of the institution.

The traditions of L’Arche, which include solidarity, hospitality and true friendship are practiced in the everyday ordinary activities of their communities – working, eating, and celebrating – to the extent that, as Mr Vanier once said, it was not possible to really know who is helping whom.

These traditions represent what L’Arche is all about, namely communion and belonging which is what distinguishes it from some other institutions that provide care ‘for’ people with disabilities. Rather, L’Arche is where people who have perhaps experienced terrible loneliness and isolation in their lives find their home in an atmosphere of true friendship – that is, friendship understood as a ‘mystery’ reflecting the common origin of all in God.

So, what can we learn from L’Arche?

Solidarity

L’Arche witnesses to the importance of solidarity – of standing with and for others. These others, particularly those with disabilities are not ‘clients’, in the common understanding of the word.

Rather, in L’Arche, each is a brother or sister and neighbour of the other. Solidarity is not, in the words of Pope St John Paul II, merely “a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far.

On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all”.

Solidarity is achieved in L’Arche when each puts himself or herself at the service of the other. Pope Francis too reminds us of the necessity of sharing our very selves when we act in solidarity with others; without faces and stories, human lives become statistics, and we run the risk of bureaucratising the sufferings of others. Bureaucracies shuffle papers; compassion (not pity, but com-passion, suffering with) deals with people.

L’Arche is not just a fellowship of people who are nice to one another. At its heart, it understands and embraces human suffering and vulnerability, and it is that very fragility which draws people together into communion. There is solidarity between core members, assistants, and the wider L’Arche family, blessed by the God who, as Jurgen Moltmann writes, “humbled himself and takes upon himself the eternal death of those perceived as worthless, of the godless and the godforsaken, so that all those the world sees as worthless, and all those who see themselves as godless or godforsaken can experience communion with him”.

In a world of division, L’Arche is a model of true solidarity.

Radical friendship

L’Arche began with the question, ‘will you be my friend?’, and since 1964 the answer continues to be ‘Yes’. The daily loving encounters between its members confirms it as a place of radical friendship. Jesus said he came that we might have life in abundance.

This fullness of life comes to us through loving and being loved and is the mark of the life lived in L’Arche. Reflecting its Christian heritage, L’Arche practices this type of loving friendship that finds its source in Christ and his radical love of ‘the other’.

In this way, we become true brothers and sisters of each other. Such fraternity is the mark of the shared life in L’Arche. Indeed, Pope Francis writes that “the basis of fraternity is found in God’s fatherhood, and in God’s family, and where all are sons and daughters of the same Father, there are no ‘disposable lives’”.

Such friendship is not based on superficial similarities in interests or temperaments however. Rather it is about learning how to give and receive love.

Through this friendship practiced in L’Arche, humanity’s true nature is revealed, namely that we are brothers and sisters of each other which is the antidote to the terrible loneliness that is so widespread in our society today. This fraternity, expressed in radical friendship, has an even greater benefit where the love and acceptance that marks it can renew the spirit of those who experience it to the extent that they regain the hope they had lost.

Friendship of this kind involves a risk – that of dying to the self for the sake of ‘the other’, and L’Arche witnesses to this in its life and work.

Hospitality

L’Arche practices hospitality in the way it practices solidarity and radical friendship – with a special concern for those who are rejected or lonely. One of the most familiar expressions of hospitality is the sharing of a meal. It is food that provides nourishment for the body, while conversation and the sharing of stories renew the spirit.

I remember vividly the two occasions on which I had the great pleasure of visiting L’Arche and sharing a meal with the core members and assistants. I remember it because I have rarely experienced such joyous hospitality. L’Arche’s way of showing hospitality has the feel of a celebration to me. Nothing was rushed and we all took our time eating, telling stories and listening to stories from others.

There were arguments and disagreements too, but I learned that true hospitality is about opening the heart to the other, even if at first we feel that we have little in common with that ‘other’.

It is about forging relationship through the sharing of our time and our stories, and paying loving attention to others, and being open to receiving all of that in return.

****

Christine Pohl, writing about the practice of hospitality, comments that those who are hosts “make room for those with no place, sharing themselves and their lives rather than only their skills. They offer hospitality in response to the people and needs they have encountered – need for nourishment, place, safety, justice, friendship, and the knowledge of God’s love and grace”.

It was difficult to distinguish host from guest at that dinner table. It was as if each was both host and guest.

One of my favourite stories about the transformation of loneliness and fear, into hope and joy, centres on a meal. In the story of the walk to Emmaus in Luke’s gospel we meet Jesus’ followers, lonely and despondent, encountering a stranger on the road.

Their conversation made their hearts “burn within them”, and they invite the stranger to stay and eat with them. Through the sharing of this meal, where the bread is blessed, broken and shared, Jesus’ followers, until that point filled with sadness, have their eyes opened and are renewed.

The recognition by the disciples of their Lord in the breaking of bread sends them back to the city full of joy which they want to share with everyone. L’Arche, in its practice of hospitality where bread is broken and shared witnesses to the hope that loneliness and rejection can be transformed into joy.

We have to give the experience time to come home to us before it can become a motive for hope and a promise of fuller life”

L’Arche should be proud of its quiet witness to the sacredness of every person, irrespective of ability or disability. Many of our brothers and sisters with disabilities who find a home in L’Arche had previously lived in hospitals and institutions where they were ignored and forgotten. Some had even been rejected by family, unwilling or unable to care for them.

The presence of L’Arche in a world that understands and values success in a manner that would exclude many with disabilities offers hope to those who are so often cast aside and ignored.

Since the publication of the recent report, many in L’Arche are now in mourning. Reflecting on loss and death, Sr Maria Boulding writes that we need time to come to terms with it. “We cannot short-circuit human processes,”she writes, “we have to give the experience time to come home to us before it can become a motive for hope and a promise of fuller life.”

That the life of someone with a disability, regarded by many as being of little value, can indeed be a life lived to the full, is what L’Arche gives witness to, and my hope and prayer is that it continues to do so. L’Arche is necessary, and we should support its work in whatever way we can.

Dr Liam Waldron is a pastoral theologian, writer and lecturer. His PhD dissertation was a theological treatment of the problem of loneliness among people with intellectual disabilities. He writes about and speaks internationally on issues related to disability and health care from a theological perspective.

Jean Vanier

Jean Vanier