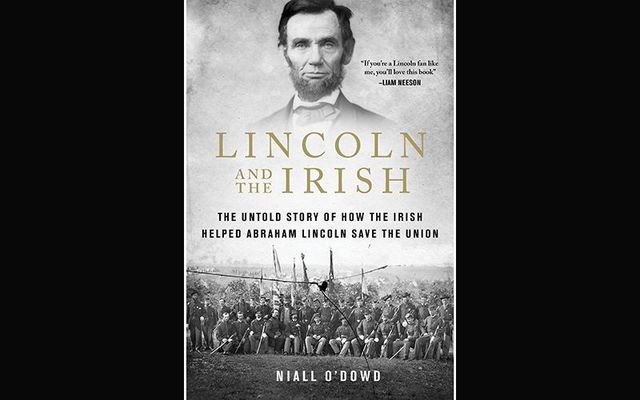

Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union

by Niall O’Dowd (Skyhorse Publishing, €20.67/$24.99)

Peter Hegarty

Niall O’Dowd has an original take on the American Civil War: without the 150,000 Irish soldiers who served in the his armies, Lincoln’s Union would have lost.

The Irish-American publisher emphasises difficulties the president faced during the conflict. In the Union states people were divided over slavery. In the field nimble, well-led Confederate armies inflicted defeat upon defeat on their opponents. Behind the Confederacy stood Britain and France, who kept arms flowing to the slave states. These powers hoped that a southern victory would permanently dismember the United States, their nascent rival.

Clearly then, Lincoln needed all the allies he could find. It must have heartened him to hear of the hoisting of the Stars and Stripes over Old St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. Tyrone-born Archbishop John Hughes, the most important Catholic prelate in the US, raised the flag to demonstrate his support for a freely elected president and national unity.

Another popular and influential Irish-American who supported Lincoln was John Francis Meagher, a former Young Irelander who had escaped confinement in Australia. He made his way to New York, to the delight of his compatriots there. Meagher, like the archbishop, was troubled more by the prospect of southern secession than by slavery.

These influential men swung the Irish behind the Union. Initially Irish immigrants had taken little interest in the conflict. Slavery was an “abstraction”. Many Irish people opposed it, but “did not want to fight and die to free slaves”.

People admired Lincoln for having called for Irish freedom, but few wanted to have any truck with his Republican Party, which was avowedly anti-Catholic. Irish people tended to support the Democrats, who were not committed to abolition.

To complicate the story even further life was easier for Catholics in the southern states, where the anti-Irish nativists – the ‘Know-Nothings’ – had less influence. Some Irish Catholics in the South even threw in their lot with the Confederacy, most notably Young Irelander John Mitchel.

Lacking a firm position on slavery the Catholic Church offered no guidance to the faithful. Some bishops opposed slavery, while others supported it, some of them most enthusiastically. Bishop Lynch of Charleston for example kept 95 slaves of his own. He condoned the rape of black girls by white men on the grounds that it kept white woman pure.

Many of the Irishmen who responded to Meagher’s call did so in the hope of receiving advanced military training ahead of the next round with Britain. Others – including immigrants fresh off the boat – joined involuntarily, duped or “shanghaied” into going to war.

Difference

The Union ran an effective recruitment campaign in Ireland. Towards the end Irish troops “were making the difference” in the “awful arithmetic of war” as the Confederacy simply ran out of men.

600,000 people – three percent of the population of the United States – died in the fighting. Many Irish troops suspected that they were being used as cannon fodder, “so often were they in the front ranks, and holding the hardest ground”. The Irish-Americans who rioted against the imposition of a draft, in New York, in 1863 were also protesting against the “wanton sacrifice” of their compatriots.

But without that sacrifice, O’Dowd tells us in his accessible, engrossing book, the United States would have been emasculated, and recent world history might have taken a very different course.

Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union

Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union