The Camino de Santiago was a very different experience in the Middle Ages, writes Greg Daly

A biography of Red Hugh O’Donnell, written a few years after the Gaelic lord’s death in 1602, made much of how the earl had visited Breóghan’s Tower in A Coruña on his arrival in Spain in the aftermath of the defeat at Kinsale.

The tower, a Roman lighthouse, had been a regular feature of Irish literature for centuries, with legends recording at least from the 9th Century how the Milesians, the mythical ancestors of the Gael, had seen Ireland from the lighthouse and set out for the country from it. It was fitting that an Irish leader had visited the spot from which his ancestors had first seen Ireland, the biographer observed.

Curiously, however, the biographer passed over in silence the other Galician site to which the defeated rebel had made a pilgrimage: Santiago de Compostela, where he paid homage to what he believed to be the relics of St James the Great. It may simply have been that politics, rather than religion, was the focus of his text.

Details like this pack Dr Bernadette Cunningham’s latest book, Medieval Irish Pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela, which maps in fascinating detail the pilgrimage cultures of the Irish and wider medieval world.

“I was already a historian before I ever did the Camino, I had written other books,” she says. “But then I did the Camino as a summer holiday project over several years so I did know several of the historical routes, and what struck me as I was doing it is just how totally rooted in the medieval world it is, even now – the number of medieval churches and sites and hostels and things like that which you encounter along the way. So for a historian it’s an extraordinary adventure into the past in itself, just actually walking along any of these routes.”

From Galway originally, the Royal Irish Academy librarian began her PhD on the 17th-Century Annals of the Four Masters in 2002, working during the academic year and taking summers off to walk the Camino in instalments from the French town of Espalion, subsequently walking the Portuguese Camino from Porto and part of the way from St Gallen in Switzerland on a route that would take her to Le Puy.

Evidence

She had no intention when she began walking the Camino of writing a book about it, being prompted to do so only a few years ago when the Camino Society of Ireland expressed an interest in the history of Irish pilgrimage to the Spanish shrine.

Asked what the most striking thing she discovered over the four years she worked on the book, she points immediately to how much evidence there was about female pilgrims.

“Normally when you do research on medieval Irish history or early modern Irish history, it’s very hard to find any information on women, but almost half the evidence I got in researching the pilgrimage related to women pilgrims,” she says.

“They’re much more prominent in that than they would have been in other aspects of life. The sense comes across of all these independent-minded women who wanted to save their souls, and headed off to Santiago without immediate family support.”

While it is easier to recover stories of women pilgrims than one might expect, there is nonetheless the eternal problem that the stories that have come down to us are perhaps more likely to have been exceptions rather than rules.

“The ones you’re more likely to hear about are where the pilgrimage went wrong, where somebody died on the way or something like that. They’re more likely to get recorded in the annals for that reasons,” she says. “There is that whole silent majority that went there that we don’t know their stories because they just went and came home and nothing weirdly adventurous happened.”

While it’s rare that the name of more than a dozen or so pilgrims have come down to us from any given year, the presence of pilgrim hostels in such towns as Drogheda and Waterford suggest that numbers may well have been far higher.

“We do have this one example of 400 people on a boat in the one year in 1473, all heading off to Santiago,” Dr Cunningham says. “So the question is was that a one-off, was that totally exceptional, or did that happen every time a jubilee year came around and there were special indulgences available? Were there hundreds going?”

Certainly, she says, in a year like 1473 there would have been at least 500 people going from Ireland, with this probably being the norm in jubilee years in the second half of the 15th Century.

“That was kind of the heyday of it,” she says. “If you think about it, that’s the kind of numbers that were going from Ireland 10 years ago. It’s grown now – it’s more now. There’s about 5,000 a year going now from Ireland. There’d be more than 5,000 on the route, but not all of them get to Santiago. They’re doing a bit of it here and a bit of it there.”

*****

One thing that is very clear, she points out, is that during medieval times significant numbers of pilgrims tended only to travel in jubilee years when the Feast of St James, July 25, fell on a Sunday.

While parishes like Palmerstown in Dublin were dedicated to St James and celebrated an annual fair on his feast day in the later medieval period, there seems to be no evidence of Irish devotion to the saint prior to the Anglo-Norman invasions.

“To a certain extent it’s a coincidence that it’s around the same time that the Normans are coming to Ireland that Santiago is being promoted throughout Western Europe,” she says, noting that most of the early pilgrims we know of from Ireland at the very least had family in England.

“It does seem that the cult is kind of an import from England in the Anglo-Norman period, and eventually then it spreads to other parts of the country later after the Black Death,” she says. “There is a time in the mid-14th Century where nobody is going anywhere, and then when society recovers from that in the 15th Century then they’re off again, and that’s when you get a lot of people from Gaelic Ireland going.”

Familiar

While the native Gaelic pilgrimage tradition tended to be linked less with relics than with places associated with saints, their mythical ties with Spain did mean something to them, helping give a sense that they would be travelling through lands that were somehow familiar.

“They had the literature, people were aware of the legends that the origins of the Gael could be traced back to the Galicians – there was a connection there,” Dr Cunningham says, adding that “it worked the other way as well – Galicians are very conscious of their links to medieval Ireland”.

Before setting sail for Spain – or before 1450 or so, first to England and then France – pilgrims had to get across Ireland, travelling by established land routes and by river to coastal ports.

“A lot of the rivers were navigable for small boats and that’s how most trade happened,” she observes. “And pilgrims are no different to merchants – they’d use the same routes as merchants were using. They’d use the same infrastructure. And even these hostels I talk about in various places that were on the coast, they wouldn’t have been exclusively for pilgrims. They would normally have been attached to a religious house and merchants with no particular connection to the Augustinians or whoever would stay in the same place as when they were in port.”

Pragmatism was, in other words, a key part of the medieval pilgrim experience, in sharp contrast to modern pilgrims.

“They wouldn’t necessarily be as obsessive as we are about it – you know, you must walk every inch of it – if somebody offered you a horse you’d hop on and head off that way. Nowadays on some parts of the route, they send you up every hill and down every valley, whereas the medieval people would have taken the easiest or most direct route they could find.”

Difference

Another key difference was that for medieval pilgrims, Santiago may well have been the destination for their pilgrimage, but it was only the midway point in their travels.

“You were only halfway when you got there and you had to get back again, when it wasn’t any easier getting back home, whereas now we’ve a completely different concept now: we go and walk a bit and fly home again,” Dr Cunningham says, explaining that today’s Irish pilgrims do at least tend to be better informed than their medieval predecessors.

“It certainly much more organised and people are much better informed about it in advance – they’d nearly all have read up something about it before they go,” she says. “It always was an adventure as well as a pilgrimage, but I think the adventure element of it is greater now and it’s less focus on the actual pilgrimage. For most people that go now, I’d say at least 50% of it is we’re going for a nice long walk in the countryside.”

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, however, point to how medieval pilgrimages weren’t always sombre affairs, and Dr Cunningham agrees that it’s difficult to tell how much medieval pilgrims looked on the Camino as an adventure.

“It’s hard to know what percentage of it was always adventure, because when you think about it, a lot of these people had very confined lives normally. You couldn’t travel very far very easily so heading off all the way to Spain was a big adventure in their lives, and it was something it only do once or twice in your life at most,” she says.

“There would have been a very strong sense of ‘you’re going there to get your indulgence’ in a way that’s not there anymore,” she adds, noting the sharply religious emphasis of the medieval Camino.

“It was focused on the Mass and Confession, and performing all the rituals. They actually did have a ritual where you went up to the altar and you made your offering and got your indulgence,” she says, comparing this with modern pilgrims queuing at the cathedral office to get their certificates.

“But there would always have been a tourist element of it, where you’d go off then and buy your souvenirs, look around, and wait for your transport home.”

Some things, at any rate, don’t change.

Bernadette Cunningham’s Medieval Irish Pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela is published by Four Courts Press.

Greg Daly

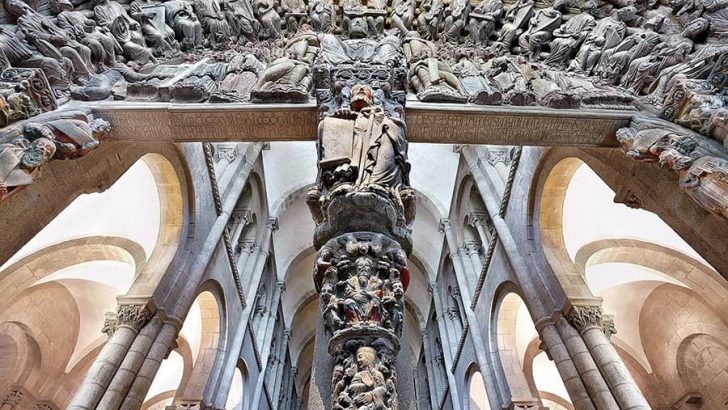

Greg Daly The restored Portico of

Glory at Santiago Cathedral

The restored Portico of

Glory at Santiago Cathedral