Joe Carroll

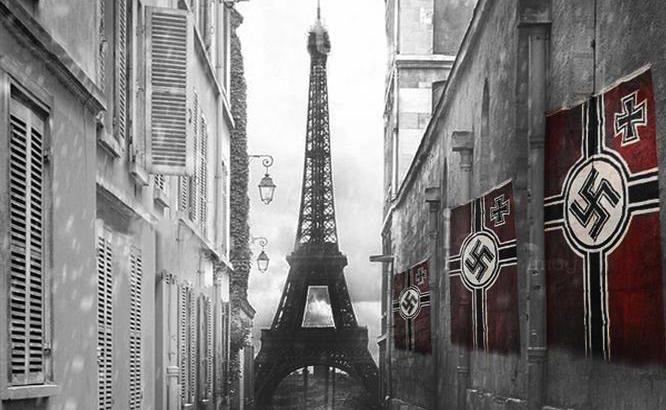

When World War II broke out in September 1939, it left many hundreds, possibly more than a thousand Irish men and women living in France with a dilemma; whether to seek refuge in neutral Éire or hold on to see what would happen. For those who were still there following the fall of France and the German occupation in June 1940, it was too late to have a choice. They were stuck there until the war ended five years later.

In this magnificently researched book Isadore Ryan traces the often sad but sometimes heroic fortunes of many of the Irish trapped under Nazi rule. Through the use of Irish, French, German and British archives he traces the experiences of these latter day “wild geese” as they struggled to survive internment, near-starvation and isolation.

As an unsung hero of the survival of many of the Irish in wartime France, the author picks out the colourful Count Gerald O’Kelly de Gallaghet de Tycooly, originally from Gurtragh, Co. Tipperary. He saved many of them from total destitution and possible death by issuing temporary Irish passports from his wine-exporting business in Paris after the Irish ambassador, Sean Murphy, had been forced to move to Vichy, the capital of the collaborationist French state under Marshal Philippe Petain.

There was a rich irony in O’Kelly’s new role. He had been appointed the first official Irish minister to France in 1929 after serving in the British Army in World War One and in the fledgling Irish diplomatic service in the 1920s in Geneva.

There he helped get the Irish Free State a seat in the League of Nations. But after serving only five years in Paris he found himself out of a job after Fianna Fail had come to power. He is said to have offended Eamon de Valera on a visit to Paris when in answer to a question of what the French thought of the Irish, replied: “They do not even notice we are there.”

The offence was compounded when his wife, Marjorie, remarked to de Valera: “I did not know you were in prison.”

Counsellor

The Count (the title was bestowed on an ancestor by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria in the 18th Century) became an unofficial Irish ambassador in Paris from 1940 as a “special counsellor” while Sean Murphy and his staff were stuck in Vichy.

Thanks to O’Kelly, the many Irish who were living in France with their outdated British passports from pre-1922, were able to get temporary Irish passports and thus escape being interned as British aliens. When strings had to be pulled to get some Irish out of custody, O’Kelly used his high-ranking German contacts and wine customers. One of these was said to be Hermann Goering during his frequent visits to Paris.

The book also details the role in helping stranded Irish women in Paris played by St Joseph’s Church on the Avenue Hoche run by the Passionist fathers and the hostel in nearby Rue Murillo run by the Poor Servants of the Mother of God.

The two Irish diplomats in Vichy gradually took over much of the paperwork for the Irish exiles and arranged for them to receive a small monthly allowance for which their relatives were charged. The author has harvested much fascinating information on their lives in wartime France from this correspondence including the travails of Samuel Beckett and James Joyce’s family.

The Irish College in Rue des Irlandais was kept out of German and French hands by the efforts of its sole occupant during the war, the Vincentian, Fr Vincent Travers, who stayed on when the seminarians escaped back to Ireland. The Irish bishops responsible for the college did not do much to preserve it either during or after the war. It is now a Franco-Irish cultural centre.

After the war Count O’Kelly moved to Lisbon where he was given the title of “minister plenipotentiary” but was refused ambassadorial status by Dublin. This annoyed him and his complaint of being “the worst paid diplomat” in Lisbon made headlines. According to his nephew, Brendan O’Kelly, a repentant de Valera later admitted “we have done wrongly by this man”.