Dublin from 1970 to 1990: The city transformed

by Joseph Brady (Four Court Press, review of Joe Brady, €24.95 / £18.50)

This new book by Joseph Brady marks the conclusion of a series devoted to the development of Dublin city, or perhaps we might say the Dublin region, since circa 900 AD, Joseph Brady is a geographer and formerly Head of the UCD School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy. He is also, with Ruth McManus, the overall editor of The Making of Dublin City series.

The author has long been engaged with the changing engagement of people with their environment, which is what geography is really about.

Dublin

This book is about the emergence of the urban region we call Dublin, but in the course of what Dublin has recently become, the author casts inadvertently and indirectly, light on the decline of the Church as an institution and the reduced presence of religion in our modern city.

Some years ago when writing a book about Dublin’s Churches, a sort of gazetteer of religions in the city, I was strongly taken by a few things.

One of these was the development of Churchtown, and a little earlier, of Marino.

Churchtown illustrates better what I mean. When one looks at the plan of the district, one is struck by the total overall social basis of it. It was designed for living, and not merely for some developers’ overall profit.

For some years in the 1950s and 60s the Catholic Diocese published a directory of parishes which contained a fold-out Ordnance Survey map on which the parish boundaries were drawn in red.

In Churchtown one could see how the Church, schools, and shops formed an essential social core to the place, and how the streets with the new homes spread out from that in an ordered way.

The place was planned for the people to live, to rear their children, all with within a deliberate scheme. Here there was room to both play and pray.

“Anyone wanting to understand modern Dublin will have to read and digest this book – and indeed the other in the series. But it also leaves much unsaid”

These days as this book clearly illustrates, development despite the constant talk about planning, is merely an attempt to take control over rich international developers, largely interested only in increasing the rentable floor space, rather than creating a place to live.

Indicatively in the index book of 450 pages there are no entries for Church or religion. Today in a development such as Cherrywood – readers can visit the scheme online – many features are presented, largely the benefits of its connection with other places, with the city centre offices that are deemed central to life. There is no allowance for churches, for convents, gospel halls, a central building for meetings, a theatre for amateur dramatics, or a library / bookshop.

The place becomes somewhere to eat and sleep, but not to grow one’s mind, body, or spirit. There is a park, but no swimming pool. We can see that what was once thought essential, a church or two is disregarded, as are small shops, places of entertainment for young people not dependant on drink.

As Joseph Brady describes, the city has been transformed, but has it been improved? But walking around the city these days, one may well be dismayed at the condition of many churches – Westland Row for instance, and those semi-closed inner city churches such as St Paul’s.

But one then notices that religion is not quite dead, though the new amenities are not the Catholic or Anglican fanes of yesterday, but small places of worship and prayer which are part of the focussed life of our new neighbours, a small mosque, a Sikh temple, a Chinese evangelical meeting place.

In the 1940s and 50s Dr Charles McQuaid desired to build great basilicas as part of his urban transformation, Basilicas for the future. But now that future has come, we find that what might really be needed are not basilicas, but “a small upper room” where a new start of some kind might be made, or rather an original continuity, smaller places for greater faith, heralds perhaps of another kind of transformation.

This is an important book, important not only for it tells us in great and admirable detail, but also for what it passes over in silence. Anyone wanting to understand modern Dublin will have to read and digest this book – and indeed the other in the series. But it also leaves much unsaid.

Peter Costello

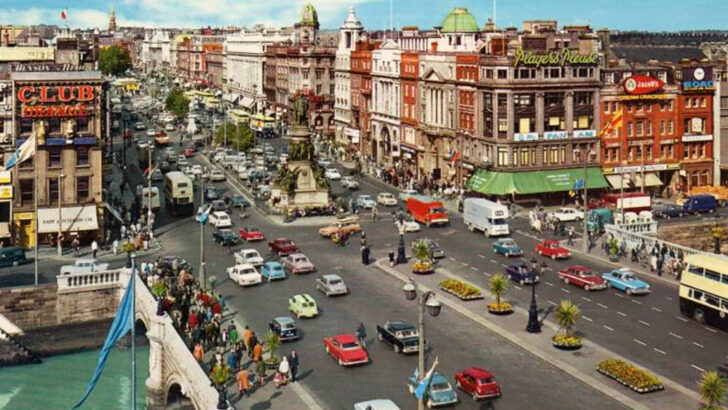

Peter Costello O’Connell Bridge and Street in the 1970s. Picture: Photos of Dublin

O’Connell Bridge and Street in the 1970s. Picture: Photos of Dublin