The View

In her 1979 essay ‘Let Us Not Be Hypocritical’, the late Harvard professor Judith Shklar wrote that: “Hypocrisy remains the only unforgiveable sin even, perhaps especially, among those who can overlook and explain away almost every other vice.”

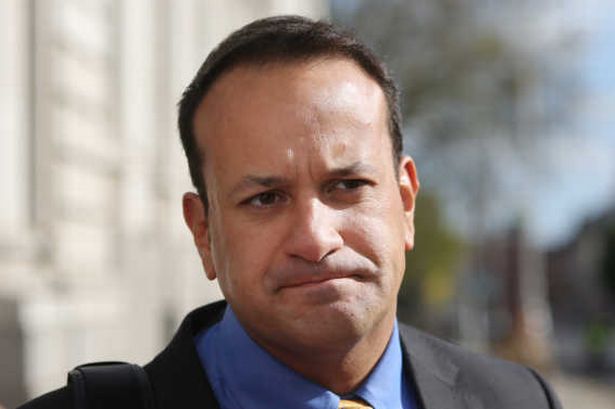

I found myself reflecting on this idea recently, when the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, got into hot water after he likened the Fianna Fáil leader, Mícheál Martin, to “one of those parish priests who preaches from the altar telling us to avoid sin while secretly going behind the altar and engaging in any amount of sin himself”.

Varadkar later issued a perfunctory apology to those offended by his remark, in the course of which he told us, with a chuckle, that what he had really been taking aim at was “the sin of hypocrisy”.

Charges of hypocrisy are the favourite weapon of those whose mission it is to destroy the notion of sin, particularly in relation to sexual conduct and the egregious sexual conduct of a small number of priests has provided a lifetime of ammunition to those who oppose the Church’s teaching in this area.

Moral component

Many of those opponents think of sexual conduct as nothing more than an expression of preference, without a moral component, so long as the weak constraint of ‘consent’ is observed. The fact that the Catholic Church remains the last major bastion in the western world of a different outlook has made it a prime target. In this regard, the Church’s high standards render it particularly vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy. Why, its opponents rail, should we listen to you telling us to do this, or not to do that, when your own clergy fail to live up to the same standards? This is easy political rhetoric, but no less effective for that.

Varadkar’s accusation of hypocrisy boils down to this: failing to practise what you preach. When this understanding of hypocrisy is combined with a political culture that is eager to condemn the hypocrite, a major problem is created.

It is this: no sensible person, with an eye to fostering a promising political career – or any other career in the public eye – should ever propose a standard of behaviour which it will be difficult for him or her to live up to. Even the expression, ‘live up’, suggests the possibility of failure, of falling below the standard. The smart move – politically – is to deny that there is a standard. No standard means no hypocrisy. The outcome is that expectations are lowered, the effects of which are felt throughout society.

Conduct, by contrast, can and should be judged”

The Church is duty-bound to teach the moral law, even though its teachers will themselves fail to follow it. Some of those failures are themselves very serious, and deserve to be treated as such. But the primary crime is the failure itself, not that the teacher could not live up to the demands of the lesson, or that the lesson was too demanding.

What is, perhaps, most interesting about Varadkar’s comments was his reference to hypocrisy as a “sin”. The concept of sin indicates an objective moral order, which is the very thing those most ready to cry, “hypocrite!”, wish to deny. It is precisely because Catholics recognise that there is a morality that does not depend on our own preferences, or on our ability to live up to its demands, that we must always risk the charge of hypocrisy.

This is not to say that we should be quick to judge people. On the contrary, we should be acutely conscious of our own failings and, as Christ said, should remove the log from our own eye before trying to remove the splinter from that of our brother. Conduct, by contrast, can and should be judged. It is an error of modernity to suppose that those who point out that certain conduct is wrong must implicitly be saying that they are “better” than those who engage in that conduct.

This approach to hypocrisy was highlighted recently in an interview conducted by Piers Morgan on his Good Morning Britain programme with a Dr David Mackereth, who lost his job as a medical disability adviser with the Department of Work and Pensions in the UK. Mackereth, who is openly and unapologetically Christian, was fired because he refused to refer to patients by pronouns inconsistent with their biological sex. The interview was an exercise in mockery and character assassination.

Mackereth said that, as a Christian, he could not in good conscience use pronouns in a certain way (calling a biological man a woman or vice versa) as it was dishonest. He said that he did not believe a person could change his or her sex or gender. Sex and gender were the same thing, he said. To which Morgan responded: “Do you understand that that makes you a bigot?”

By not stoning himself to death, he had been ‘exposed’ as a hypocrite”

In an amazing segue, which involved the twisting of biblical and Christian teaching, Morgan stated that the Bible calls for those who are guilty of looking lustfully at another to be stoned to death. (He seems to have forgotten that Christ stopped the stoning of the woman taken in adultery by saying, “let him who is without sin among you cast the first stone”.)

In a blatant ad hominem attack, he then proceeded to ask the doctor whether he himself had ever been guilty of looking lustfully at another. Rather than rebuff the question or take offence at the way he was being treated, Mackereth answered truthfully that he had. This was all that was needed. In a move taken straight from the hypocrisy playbook, Morgan treated the admission of a failure to live up to this standard of Christian conduct as disentitling his interviewee from proposing any standards at all. By not stoning himself to death, he had been ‘exposed’ as a hypocrite. The intent was clearly to mock not only Dr Mackereth, but his views and Christian teaching also.

There is no doubt but that the Church proposes standards for conduct that are difficult to meet. As has sometimes been said, no-one promised that Christianity would be easy.

Our fallen nature means we all fall short – repeatedly. Morgan’s – and Varadkar’s – error lies in believing that this makes us hypocrites. As Prof. Shklar stated: “To fail in one’s own aspirations is not hypocrisy.” It is humanity.

Maria Steen

Maria Steen An Taoiseach Leo Varadkar

An Taoiseach Leo Varadkar