Felix M. Larkin

The Irish Parliamentary Party at Westminster, 1900-18

by Conor Mulvagh

(Manchester University Press, £75.00)

The centenary commemoration of the 1916 Rising last year was marred by the curious incident of the banners on the facade of the Bank of Ireland building in College Green.

These banners were a minimalist attempt to commemorate at the home of the pre-1801 Irish parliament some heroes of the Irish parliamentary tradition – Grattan, O’Connell, Parnell and John Redmond – and their contribution to the achievement of an independent Irish state and to shaping the political culture of the state.

But the Sinn Féin members of Dublin City Council led a chorus of complaints about the banners on the grounds of (as reported in the press), “their seeming inappropriateness in the context of the 1916 Centenary”. The banners were removed immediately after the matter was raised at Council meeting.

That incident symbolises the regrettable tendency in independent Ireland since 1922 to denigrate the great popular Irish constitutional leaders of the 19th and early 20th Centuries, reducing them to peripheral figures – a species of quisling, prepared to compromise with the “hated oppressor”.

The Irish parliamentary tradition has, however, been well served by our historians. The groundbreaking work of Oliver MacDonagh on O’Connell and of Conor Cruise O’Brien and F.S.L. Lyons on Parnell and the Irish party at Westminster has been supplemented by more recent work by Patrick Geoghegan on O’Connell and by James McConnel, Dermot Meleady and Michael Wheatley on the Irish party.

Conor Mulvagh’s book is an important addition to the corpus of work on the Irish party.

Focus

Mulvagh’s focus is on the leadership of the party in the period from 1900, when the so-called “Parnell split” was healed and the party re-united under Redmond, until the death of Redmond in March 1918 and the subsequent demise of the party itself in the General Election of December 1918. He takes issue with what he refers to as “the recent vogue” for treating Redmond “as a strong and charismatic leader of the parliamentary party”.

He demonstrates that there was, on the contrary, a collective leadership in the period under consideration – comprising John Dillon, Joseph Devlin and T.P. O’Connor, as well as John Redmond. The leadership is thus characterised by Mulvagh as a tetrarchy – and much of this book is concerned with the twists and turns within that leadership structure.

Chairman

Employing Brian Farrell’s typology in his assessment of our taoisigh, Mulvagh regards Redmond as a chairman rather than a chief.

However, Mulvagh’s book also shows that the tetrarchy at the head of the party – “a very narrowly based oligarchy”, to quote Mulvagh – dominated the party. Dissidents originally within the re-united party of 1900, notably Tim Healy and William O’Brien, were ruthlessly excluded.

Moreover, the leadership failed to recruit new blood into its inner ranks – except for Devlin, each of the tetrarchs had been MPs since the early 1880s – and this contributed to a de-radicalisation of the parliamentary party and declining participation by rank-and-file members at Westminster.

Mulvagh traces this gradual drift away from the crusading roots of the party under Parnell through a detailed analysis of parliamentary questions tabled by Irish party MPs.

This analysis, and a similar analysis of the voting record of the party members at Westminster, is further used by Mulvagh to illustrate the strong party discipline imposed by the collective leadership.

Efficacy

He argues that these analyses confirm “the efficacy of collaborative government within the party … loyalty did not leak, it simply mutated to conform with the shifts developing in the ruling oligarchy”.

Mulvagh concludes his study by drawing a vital lesson for all political parties by reference to the history of the Irish party. He writes: “Where discipline is prized, innovation is excluded and the party that shuts out the talent of the next generation will re-encounter these potential political allies, not as friends, but as enemies either on the streets or at the ballot boxes”.

That was the fate of the Irish party in 1916, and again in 1918.

As the incident of the banners in College Green at Easter 2016 indicates, the reputation of the party – and, by extension, that of the entire Irish constitutional tradition – has not yet recovered.

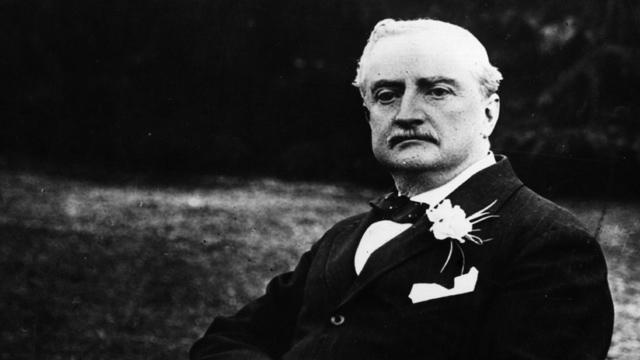

John Redmond

John Redmond