John Redmond. Selected letters and memoranda, 1880-1918

edited by Dermot Meleady (Merrion Press, €29.99/£26.99)

Ian d’Alton

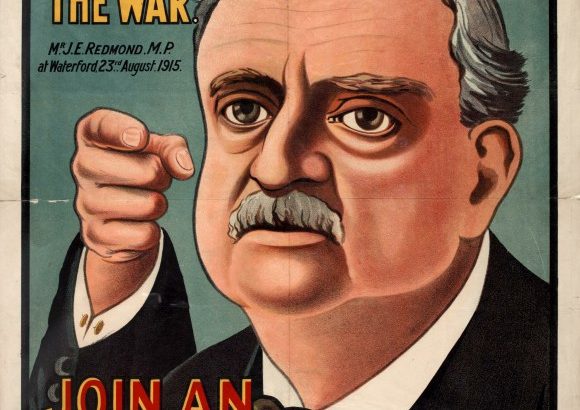

On March 6, 1918, John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, died – “a broken-hearted man”, in his own words – at the relatively young age of 61 years.

History was in the process of overtaking him, and what he stood for, as Sinn Fein powered up the outside lane.

It was perhaps wholly appropriate that his last major political engagement was with the Irish Convention – that sepia-tinted gathering of Irishmen in 1917-18 with its bishops and archbishops, every gradation of the peerage, sullen northern unionists and a gaggle of county council chairmen politically out of step with the country’s mood.

Less than a year after his death, Redmond’s party was no more and the first Dáil was a radically different assembly to that which had met inconclusively in Trinity College.

The Convention, Redmond’s last hurrah, summed up what he was about – conciliation, attempts to square circles, the desire to keep Ireland united and self-governing, but also to remain part of the important economic and political nexus of Empire, and to construct a conservative, Victorian Ireland. And perhaps the best tribute to Redmond – although it is now not often admitted or acknowledged – is that is what Ireland (north and south) broadly got after 1923. Redmond had had the potential to deliver without the violence of the 1916-21 period, though it is moot whether even if Home Rule had been put in place, he might have still have ended up as the Kerensky of Irish politics.

The ‘considerations of honour’, as he put it in relation to his initial support for the Great War, cut little ice with the revolutionaries of the ‘vivid faces’ generation.

Dermot Meleady is Redmond’s foremost modern biographer, and the author of Redmond: the Parnellite (2007), and John Redmond: The National Leader (2013, 2018). The author’s deep and special knowledge of his subject is evident in the judicious and illuminating selection of correspondence (to, from and about Redmond) and memoranda, covering the nearly 40 years of his political career. The personal, however, is not ignored.

The first document from Redmond is a telegram to his mother in November 1880 – “Father is in Heaven died in my arms yesterday”– and the last is about making “slender provision” for his family when he died. In between is a cornucopia that gives us an insight to Redmond’s character, politics and personal relationships.

Insightful

Meleady writes an insightful short introduction in which, through Redmond’s papers, he refers to Redmond’s courteousness, businesslike style and self-discipline.

His relationship with the Catholic Church, especially after the Parnell split, is laid out here; his second marriage to a Protestant does not seem to have affected what Meleady calls his “personal Catholicism infused with a positively Spartan sense of religious duty…”

Meleady takes on those who criticize Redmond for not holding to what Ronan Fanning characterized as “the nationalist delusion that the partition of Ireland was avoidable”.

He points out that O’Connell, Gladstone and Parnell never had to face up to the issue properly, since none had carried the Home Rule project as far as had Redmond. In that success lay the seeds of failure, as he came up against an intransigent Ulster, notably in the Convention.

This is a well-put-together, coherent view of Redmond the man and the politician. It repays dipping into. Many significant and not so significant characters grace its pages, from Alice Stopford Green to Asquith, Parnell to William O’Brien, Carson to Churchill. Meleady keeps the whole rattling along, with short but judicious explanatory inserts which ensure that the reader is not perplexed.

Two of Redmond’s closest colleagues were John Dillon and T.P. O’Connor – not always on his side. They feature heavily in these pages. On April 6, 1918, Dillon wrote to O’Connor about Redmond’s death, in a phrase that still resonates today – “…his fate is a terrible warning to all Irish leaders who have to deal with British statesmen…”