Pilgrimage: Journeys with Meaning

by Peter Stanford (Thames & Hudson, £25.00/€30.00 approx.)

Peter Stanford, a former editor of The Catholic Herald, is also the author of a long series of books that explore aspects of Christianity from a Catholic point of view which manage to appeal to a wide audience through his skill in making the often complex material accessible in a graceful and appealing way.

His latest book is a fascinating study of the varied nature of pilgrimage in the modern world. It is often said that religion is in decline, but the evidence of others and of our own eyes suggests otherwise. One comes away from this book impressed how religion, a many-headed hydra if ever there were one, shows great signs of resilience. So we can follow the trail of Peter Stanford with much benefit to our minds.

It turns out to be a mind-broadening experience. He begins his exploration in search of the essential nature of religion and travel with what is today the most ‘relevant’ pilgrimage in the world, one which seems to suit everyone, whatever their ideas and beliefs. Travel is of the essence of the matter, but pilgrimage is something more than a mere aspect of tourism, though both are confusedly mixed. Mr Stanford attempts to untangle them.

Thus he starts with the Camino, which is perhaps the most fashionable route to follow. To get to Compostela, to the tomb of St James’, or the shore where the boat carrying his supposed relics from the East were landed. Every kind of character can be found along ‘the way’, as we can regularly read in the annual books in many languages that appear.

Heritage

But from this ultra-modern activity, he plunges back into the past to Jerusalem, a city with a now complicated pilgrimage heritage. This is built around the quest of Helena – the Emperor Constantine’s mother – for relics of Jesus, which eventuated in the discovery of the True Cross. Given a new focus, from all over the Christian empire pilgrims set out.

So much is for most people familiar territory. But then he slips back to the first Christian century, and to the devotions paid to the tombs of Ss Peter and Paul, a key moment in the development of the new faith.

But now the author moves on to Mecca and the annual Hajj which is compulsory for all Muslim believers in a lifetime. It has now become, thanks to the facilities of modern travel, and the ruthless Saudi destruction of the past, one of the most extraordinary events in the world, the sheer teeming size of it is intimidating.

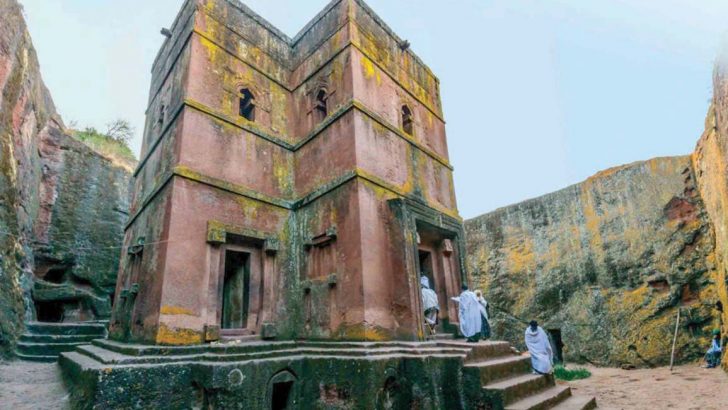

By now the reader may need a rest, and Mr Stanford provides it in the form of Lalibela, that wonderful church carved out of the living rock, a place which epitomises the whole spirit of Ethiopian Christianity, a faith that since earliest times seems to have resisted all the troubles of the world, and which encapsulates for many people a feeling of early centuries of the Faith.

Lourdes, Medjugorje, the whole blue realm of Marian shrines has inevitably to be encountered, for it certainly involved tourism, travel and faith. This chapter has, remarkably, some new thoughts about these places. Mr Stanford even manages to have a fresh insight into Medjugorje by placing it firmly in the war wracked history of the Balkans from which so many Western visitors try to draw it away.

By contrast the now appreciated Celtic shrines, in Mr Stanford’s case in North Wales – but much that he says could be echoed by Ireland and Scotland.

So far so familiar, more or less. But for nearly the last half of the book Mr Stanford travels through stranger scenes to many: to the largest Hindu pilgrimage in the world, to Buddhist trail ways, to the trail of a master in Japan. The United States finds a place in a chapter dealing with ‘optimistic hiking’ – the spirituality that derives at long distance from the notions of John Muir and others, by way of Thoreau and the Sierra Club. This, however, has developed, as it had to, into the movement to ‘save the planet’ that has rightly been encouraged by Pope Francis.

Final chapter

In his final chapter on Machu Pichu, Mr Stanford invokes again a spirituality of the wilderness, though neglecting the true reality of Machu Pichu as an expression of Inca social power, and not of engagement with creation.

The realms of pilgrimage remain strange and engaging. Mr Stanford quotes TS Elliot’s famous lines from Little Gidding of returning home to know the place for the first time.

Yet in relishing what they have achieved pilgrims should also recall the sentiment encompassed in those anonymous lines from early Christian Ireland, (a society that loved pilgrimages):

“To go to Rome / is little profit, endless pain; / the Master that you seek in Rome / you find at home or seek in vain.”

Peter Costello

Peter Costello The ancient church at Lalibela in Ethiopia.

The ancient church at Lalibela in Ethiopia.