Joyce, Aristotle and Aquinas, by Fran O’Rourke (A volume in the Florida James Joyce Series, edited by Sebastian DG. Knowles; University of Florida Press, US$90hb/US$35pb/£38.95pb /€44.50pb)

Today marks the anniversary of James Joyce’s birth in 1882, the first indeed in what can be seen as the second century of Ulysses. That book is now so well established that it can been seen, not as a “modern” book, but as a European classic.

But what exactly is Joyce’s place in European cultural history. This is one of the questions which Fran O’Rourke, emeritus professor of Philosophy at University College Dublin attempts to answer in this very full and impressive book which can be seen as crowning his professional output. It is certainly the most important book on Joyce that has been written by an Irish scholar in recent times.

Status

When Ulysses appeared in February 1922 there was great debate about its status. Why this should have been so is a little mysterious, for his early work in Dubliners (1914) had established his generous endowments in literary skills. But A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) went further. Significant passages in that book discussed in lengthy dialogues questions of the nature of literature and the aesthetics of creation.

The names that O’Rourke invokes in his title were sounded by Joyce the aesthete as bringing important elements from European philosophy to the outlook of Joyce the writer.

Now, however, Europe’s heritage of ancient classical thought and medieval scholastic culture is far less well known generally than it once was, as today it can be safely said that schools and some universities (at least in Ireland) have abandoned Greek and Latin. When elements of it appear in writers such as Umberto Eco and JB. Borges, they come as a surprise even to the most literate.

My own training at school and college was in literature, not in philosophy, so much of what O’Rourke says will pose I think a challenge to many readers.

We have to bear in mind that though Joyce had studied Latin from an early age under the Jesuits at Belvedere and Clongowes, he never did Greek; and at college he took Modern Languages (“The girl’s course” as it was known to those ambitious young men studying for clinic and Church).

When Joyce died a copy of Oliver St John Gogarty’s still recent book on St Patrick was found on his desk along with a Greek dictionary by means of which he was said to have been checking the Greek quotations; but as there are none, one has to doubt this pleasant little anecdote, typical of the legends that still surround the writer.

Surprised

I suspect, however, that Joyce must have been happily surprised to find that according to the marginal note on the surviving manuscript of the Confession by an Irish copyist (quoted by Gogarty, p237) St Patrick’s grandfather was named Odysseus – that is just the sort of allusional literary link that Joyce delighted it. It was these allusions he relished, not the integrity of the true philosopher.

So Greek for Joyce was a language dependent on translation. In Latin he was fluent, as his Trieste library indicates with its numerous Latin books on sexual matters written for the Catholic clergy. St Thomas then was a writer working in a living allusional language for him.

Prof. O’Rourke opens then with an account of this relationship. But we have always to remember too that Joyce was not a philosopher; he was an artist. Aristotle and Aquinas were used by him for structural and allusional purposes. He uses them in ways philosophers would not do. However, Fran O’Rourke is intent on exploring the whole wider context, and succeeds in doing so in a remarkable way.

Solid base

From this solid base Prof. O’Rourke moves on to examine questions of knowledge and performance. The heart of this book, however, lies in the sixth chapter dealing with the nature of beauty, a question that had absorbed Joyce, who was partially sighted since childhood. True beauty for Joyce was a matter for very close observation.

But in making use of Aristotle and Aquinas and the philosophical matters to which they gave entry, Joyce revealed himself not as a “modern” writer at all, but as an artist working in the central tendency of European culture as a whole from the Lyceum to the medieval schools of Paris.

Far from being, as so many rather foolish critics, especially in the popular press, claimed a destructive madman, he was a major figure in the mainstream, a culture bearer in ways that even many of his most fervent admirers have little comprehension of.

Fran O’Rourke’s pages will, I suspect, open up new realms to them which will be fruitfully explored in the century on which we are now embarked, and for as long as literary culture as understood by Aristotle, Aquinas and Joyce continues to exist. And long may that be.

Peter Costello

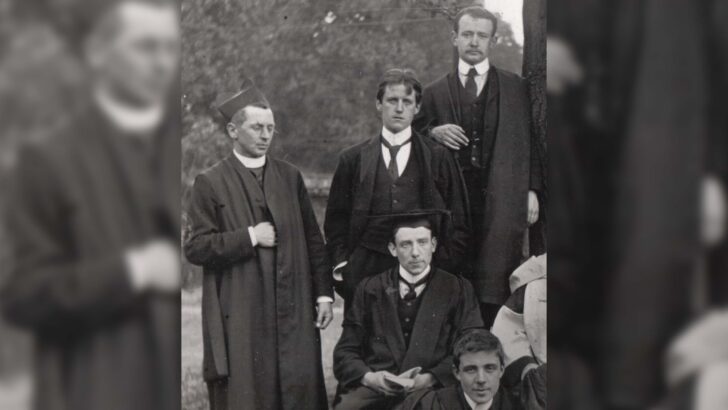

Peter Costello James Joyce (centre, standing) at University College Dublin in his academic context.

James Joyce (centre, standing) at University College Dublin in his academic context.