The Best Catholics in the World: The Irish, the Church and the End of a Special Relationship

by Derek Scally (Sandycove/Penguin Ireland, €20)

Derek Scally is a journalist with The Irish Times, based in Germany for the last 20 years. His perspective on the subject of Catholicism in Ireland is shown in the dedication of the book to his parents, “with thanks for their belief”.

Aged 44, he says he is “a member of the last generation to have a full Irish Catholic childhood”, He served as an altar boy at Mass in his north Dublin parish, but now admits to having a “shaky grasp on Roman Catholicism”.

This is an honest book and painful reading, all the more so because the author is not fundamentally unsympathetic to Irish Catholicism. He sees that it had given meaning and purpose, to the lives of successive generations of Irish people.

He conducted hundreds of interviews with members of the Church, from Cardinal Seán Brady, to the head of the Sisters of Mercy, to the people still active in his own old parish in Edenmore. He draws out their understanding of the events that influenced the decline in practice and faith among Irish Catholics over the past 60 years. He also interviewed victims of clerical sex abuse, former residents in mother and baby homes, and women who lived out their lives in places like the Magdalen laundries.

Inevitably the picture is selective. The focus is on those who suffered, or were treated unjustly in Church settings.

Counter-factual

There is no counter-factual in the sense that the book does not explore what might have happened if these Church-run institutions had never existed, and people were left to their fate.

There are no international comparisons either. The book deals with early twentieth century Irish Catholicism, as if it was something completely unique for its time. Many of the abuses and cruelties the book identifies were found in other cultures too. It is hard for a reader to quantify how uniquely ‘Irish’, or ‘Catholic’, the problems were.

The author accepts that priests and nuns have taken the blame, not only for the failings of some among them, but also for the failings of wider Irish society.

Ireland was much poorer financially when some of the abuses occurred. But lack of money is never an excuse for turning a blind eye to rape or cruelty.

Class distinctions abounded, and ‘respectability’ was at a premium. This encouraged silence about embarrassing things. It allowed ‘knowing,’ but simultaneously not ‘really knowing’, that certain things were going on.

In this, the Church reflected the evasions of Irish society, just as much as the other way around. But it is human nature that, when failings are finally exposed, the anger is directed at others, or at the system.

It is true that Irish society was shaped by strict – and sometimes unforgiving – notions of sexual morality which were inculcated by the Catholic Church. But this was not a particularly Irish, or even Catholic, thing. Victorian morality, and Victorian hypocrisy, was to be found on our neighbouring island, and further afield too. It just survived a decade or so longer here.

It was Irish families, not Irish priests as such, who banished unmarried daughters, when they became pregnant.

It was cash-strapped Irish governments which, in the early years of the State, were content to allow religious orders to take on the responsibility for running reformatories, and other institutions to shelter people, whose families who could not, or sometimes would not, look after them.

Scientific

This book is impressionistic rather than scientific. The author allows the interviewees to tell their story. It does not provide a roadmap to redemption for the Church in Ireland, or for Irish society, but it contains some hints.

Although the author thanks his parents for their belief, he admits that religion was never discussed in his home when he was growing up, “let alone personal faith”. That job was left to the school.

So it is no wonder that, when the scandals came along, people could stop going to Mass and feel good about it, without thinking what they were losing.

As Bishop Paul Tighe told the author, the Church discouraged people from asking questions: “We became a lazy Church, and we are reaping that legacy now”, he said.

Learn

The author, who lives in Germany, might usefully have studied the Catholic Church there over the last century. That might show whether there are lessons Irish Catholicism could learn, or could have learned. Equally he might have established if the Irish case is really as exceptional as his provocative book title implies.

While this book will annoy many people, it may be a spur to the necessary heartfelt and rigorous discussion about the role of faith in our society, a discussion Irish people have been postponing for a long time.

It should also prompt us to ask if this generation itself, like the previous one, is turning a blind eye to family responsibilities, like when it leaves elderly relatives unvisited in nursing homes, the running of which is now no longer delegated by Irish families to vocational nuns, but to profit-seeking corporations.

John Bruton was Taoiseach from1994-1997.

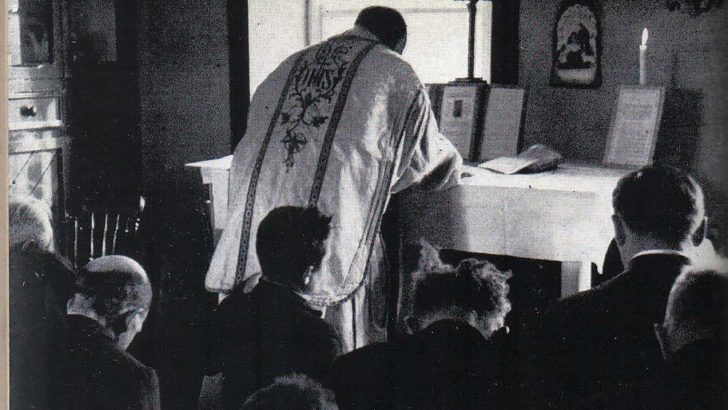

God in a Kerry Kitchen. Photo: Charles Fennel.

God in a Kerry Kitchen. Photo: Charles Fennel.