Joe Carroll

Nothing Is Written In Stone: The Notebooks of Justin Keating

Edited by Barbara Hussey and Anna Kealy (Lilliput Press, €20.00)

Justin Keating intended to write a autobiography, but died in 2009 on the eve of his 80th birthday leaving eight handwritten notebooks. His second wife, Barbara Hussey, and Anna Kealy have done their best to fashion out of these notes the life story of a remarkable man, but inevitably there are large gaps.

His active political career in the Labour party spanned 1967 to 1981, the highlight of which was his term as Minister for Industry and Commerce in the Fine Gael-Labour Coalition of 1973-77. His background was veterinary science and a short spell making agricultural programmes for RTÉ, so he was a curious choice for the post he calls a “poisoned chalice”.

He was plunged almost immediately into the 1973 oil crisis and he did not have a good relationship with fellow Labour ministers, Conor Cruise O’Brien, Michael O’Leary and Jim Tully. He admits that he did not really trust them. Possibly they were somewhat suspicious of him as an agnostic and former communist with strongly anti-clerical feelings.

He was actually closer to his Fine Gael colleague, Garret FitzGerald, who unsuccessfully tried to have him nominated as Ireland’s EEC Commissioner instead of Dick Burke in 1976, though this is not mentioned here.

He worked hard as a minister, travelling the world to drum up investment in Irish industry, pioneering legislation in oil and gas exploration and ensuring State involvement in Tara Mines. He lost his seat in 1977 in the new Dublin West constituency.

He served in the Seanad until 1981and then withdrew from active politics.

Showdown

He writes about his “difficult” relationship with Dr Noel Browne, whom he “loved” and admired for his work as Minister for Health in 1948-51. But when Keating became minister, Browne had become a fierce critic of his policy on oil and mineral resources leading to a showdown at the party conference in Cork in 1973.

Keating demolished Browne’s arguments and swung the party behind him, but writes that he went home that night “deeply troubled and psychologically exhausted”.

He was passionate about preserving natural resources on land and sea and farmed extensively in Co. Wicklow. In 1977 he was diagnosed with Paget’s disease, a painful bone condition which eventually led to deafness and immobility.

But he rose above this handicap to continue farming and to teach equine science at Limerick University. He also was prominent in the Humanist Association of Ireland.

In his notebooks he describes an idyllic early childhood on Killakee mountain where his father, Sean, combined farming along with his post at the National College of Art. There is hardly any mention of his father’s distant influence, but much about his warm relationship with his mother May.

He soon abandoned his Catholic faith, and there are constant critiques of all revealed religions, but especially Catholicism for which no words are hard enough. The child abuse scandals only confirmed his loathing for religion.

Knowledge

He read widely and applied his scientific knowledge to how the Earth’s natural resources could be preserved from both industrial and agricultural exploitation while getting barbs in at the Book of Genesis for encouraging ecological damage. He seemed not to realise that the Catholic Church in these days also disowns a fundamentalist interpretation of Revelation.

He was never afraid to change his views and became disabused of communism while continuing to admire Marx. From vigorously opposing Ireland’s entry into the EEC in 1973, he came around to believe it was the best decision the country ever made. He also switched from pro-Israeli views to an anti-Zionist position drawing down the wrath of the pro-Israeli lobby worldwide.

He was passionately anti-IRA in spite of the republican sympathies of his parents. As a 12-year-old, he had witnessed the murder by the IRA in 1942 of their Killakee neighbour, Detective Sergeant Denis O’Brien.

To add to Keating’s trauma, he had then to testify at the trial of Kerryman Charlie Kerins, who was later hanged for the murder.

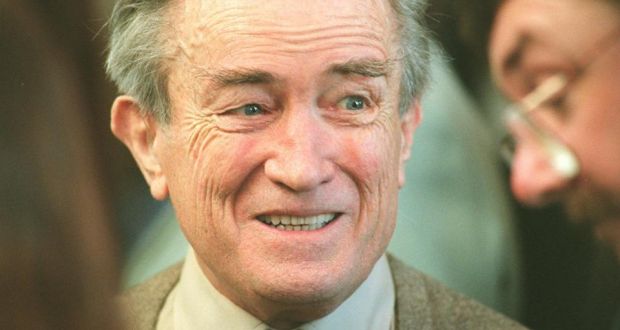

Justin Keating

Justin Keating