It takes time, they say, to get used to an idea. It is now two or three months since I heard of the closure of Mount Melleray and like many others, I am still trying to get my head around it. The closure is, I suppose, inescapable but the final, definitive announcement of such an historic event always comes as a big shock. How can I imagine that great icon of Cistercian architecture, with its characteristic monastic church and cloister, empty, doors closed, monks scattered like their predecessors of the 16th century Dissolution and all the other dissolutions and expulsions since the end of the medieval centuries? French Revolution, Kulturkampf, Communism. Melleray is gone and not a trace in sight of a Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Voltaire, Bismarck, Stalin – only a generation that no longer feels able to take up the Trappist burden. Oh, that it should come to this, the great imposing abbey no more, the same abbey that can trace its origin back, not just to 1833 when the Trappists came to Melleray after yet another expulsion from their French homeland, but right back to the beginnings of the Cistercian Order in 1098. Their antiquity, like the antiquity of the Benedictines and the Orders of Friars is mind-blowing. They have been reflecting, sub specie aeternitatis, on the vicissitudes of human life for an exceedingly long time.

Melleray

I have always been quietly proud that Melleray is in Co. Waterford. We considered it our Melleray and the monks our monks. We could go there quite easily, meet the monks, and benefit from the many human and spiritual gifts that a monastic visit can bring to the complicated thicket of our lives. “I was over in Melleray last Sunday” is a refrain from my childhood. It was a kind of shorthand that the speaker had celebrated Mass and some hours of the Divine Office with the monks, had a thoughtful stroll in the monastery garden, a cup of tea, and above all, had confession and heard a Cistsercian voice say the ancient words “… through the ministry of the Church may God grant you pardon and peace, and I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.” Who will we go to now when we seek relief from the burden of guilt? Who will we turn to when we need forgiveness for the transgressions of our youth? Who will speak words of consolation to us as we encounter illness and prepare for death (though we know not when or how)? It is only when the likes of Cistercians and Friars, and indeed our local parochial clergy, are more or less gone that we will miss the things of God about which they spoke to us season in season out. Their absence is sensed already. A lot more of that absence is fast coming down the line.

He is always aware of God’s nearness and that is the heart of his spiritual life”

‘Trappist’. The very word cries out prayer, work, focus on the things that endure. The motto of the Cistercian Order is Laborare est Orare (To work is to pray). That short phrase, seemingly innocuous, contains the whole of the spiritual life. It means that as we go about our daily work, in office, school, factory, farm, we do it more or less consciously in the sight of God. A life of prayer is a life lived in the presence of God. No strain, no sweat, no long words – just a consciousness that God is near us. When we live with this awareness, we are à l’écoute de Dieu, tuned in as it were, on God’s wavelength. When the Trappist works in the field and the milking parlour (I helped a monk there once!), he is always aware of God’s nearness and that is the heart of his spiritual life.

Cistercians

To think of Cistercians is to think of their great contribution to agriculture, clearly evidenced in Mount Melleray. In the course of their life on the mountain, they have turned the unruly wilderness that was into a beautiful, green field. They are God’s farmers. Other orders in the history of the Church have aimed in various ways at serving the society around them; the Cistercians fled from it. Given their agricultural vocation, they needed land but they did not want it in places where the chaos of nature had already been tamed by cultivation. They needed it in the untamed places, the wild, frontier terrain not yet touched by the sacred plough. Melleray in early 19th century Ireland was such a place. It was a characteristically austere locus for Cistercian life. In short, where there was unruly and chaotic land, from Middle Age to modern age, there was Cistercians to put order and smacht on it.

How I regret now that I did not go more often to Melleray”

I stayed at Mount Melleray for a couple of days on two occasions. A retreat – where better to take stock of life, surrounded by monks daily living the 1,500-year old Rule of St Benedict, day punctuated by Mass and Divine Office, atmosphere fite fuaite with prayer and silence. In such a place, human consciousness can hear the voice of God calling us to our true selves. How I regret now that I did not go more often to Melleray to imbibe more deeply this privileged way of being human! I made excuses, busy life, etc. but the feeling of loss remains. There are other monasteries, other numinous places, but perhaps only for the time being. Because are all the spirit-full places destined inevitably to be gobbled up in the general drama of post-Christian spiritlessness? After all, could the holy mountain of Melleray end up a luxury hotel pampering to what is least worthy, and not what is most worthy, in us?

Thank you, Cistercians, and may St Bernard of Clairvaux and the host of Cistercian saints go with you!

*

Maurice Kiely is from Dungarvan Co. Waterford and is a retired civil servant.

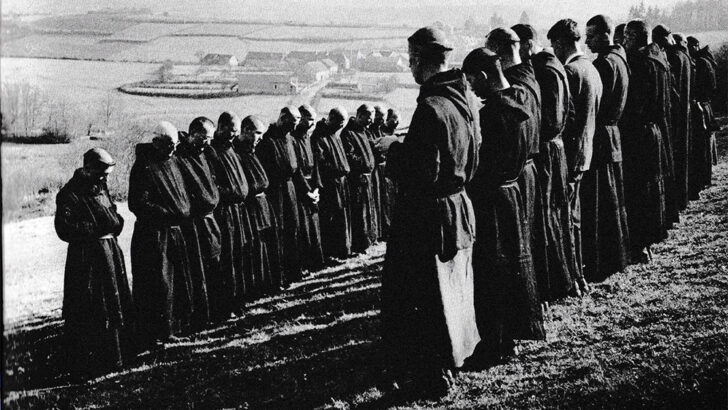

Monks at prayer in the fields

Monks at prayer in the fields