Notebook

I was at a social event recently with some high-powered academics. I mentioned at a certain point that a lot of my research and teaching centres on the theology of St Thomas Aquinas, and half the group gave me a blank look: “Who?”

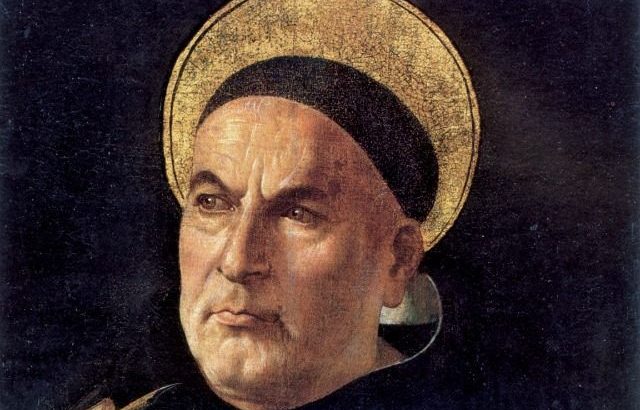

I’m sure the readers of The Irish Catholic don’t need to be told who Thomas Aquinas is, this great Dominican philosopher and theologian of the 13th Century whose writings – all 10 million words of them – are so profound and fresh that readers of every age since have been drawn to them.

The most recent generation of Thomistic initiates assembled earlier this month in the wonderful Emmaus Centre, Swords, for the eighth annual Aquinas Summer School (aquinasinstitute.ie). I’ve had the pleasure of being involved in this summer school since its inception, and its success each year continues to amaze me.

Thomas’ works are not, after all, very accessible. He’s not one for flowery speech or unnecessary jargon, but it still requires a considerable effort to understand the terms and concepts he uses. Every year, though, we welcome dozens of students, some advanced, but others complete beginners, who are willing to undertake that hard work with the help of tutors. And after pouring out blood, sweat, and tears over the pages of the Summa Theologiae, these students always unanimously agree that it was worth it. In these ancient writings they gain new access to important truths about the human person, about God, about the mysteries of the Christian faith.

Encouraging

It’s deeply encouraging to meet lay Catholics with such deep intellectual curiosity. They know that the Christian life is not just a matter of doing good deeds. They know that it’s also a matter of truth, and that our minds are made to know, if not to fully comprehend, that truth.

What’s really fascinating, though, is what happens when a group of prayerful lovers of the truth gets together: certainly there’s debate and disagreement about principles, but above all there’s great enjoyment and mutual love. Every year our summer school spills over with laughter and joyful conversation. Without much organising on our part, our students find themselves singing songs together, and praying spontaneously, and sharing beloved books. Every year deep bonds of friendship are formed.

Our relativistic society wants us to think of truth as unhelpfully ‘black and white’, unexciting and divisive, but that’s far from the case. Truth is not the enemy of fun, or friendship, or love. Far from yielding a ‘black and white’ vision of the world, the light of truth shows all things in their true, bright, God-given colours. Studying, coming to know the truth, especially in a community, is like seeing unexpected colours spread through our field of vision. And that makes for joy.

-It’s no surprise that some of the vast variety of St Thomas’ writings were translated into Irish in the Middle Ages and survive to this day in manuscripts. A medical manuscript from one of medieval Ireland’s many schools of medicine includes Irish translations of works by Thomas on topics like the activity of the heart and the mixing of the elements. A slightly earlier manuscript from Roscommon includes not only the earliest version of St Thomas’ Eucharistic poem, the ‘Adoro te devote’, but also some advice from the great saint on how to make a good Confession: it should be simple, humble, pure, faithful, truthful, frequent and so on. Good advice, as always, from the Angelic Doctor!

-I think St Thomas would be glad to know that his readers enjoy having fun. In fact, I’m sure of it. This year our topic for the summer school was ‘virtues and vices’, and in the midst of his discussion of these good and bad habits – prudence, humility, drunkenness, temperance, timidity, and so on – Aquinas mentions a virtue with a strange name: ‘eutrapelia’, best translated as ‘playfulness’.

He explains that too much thinking can lead to a tired soul. Just as a body needs rest, so does the soul, and the soul’s rest, he explains, is pleasure, or play. Without games and recreation and laughter, the soul becomes brittle, like a wooden bow that has been used too often. The truly virtuous man, concludes Thomas, must know how to tell a joke.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas