With declining numbers of priests, lay people are stepping up to lead worship, writes Greg Daly

Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention, so on Tuesday, April 25, while the clergy of the Diocese of Limerick are gathering with Bishop Brendan Leahy, every parish in the diocese is to have a lay-led liturgy service.

“It relates to the synod we had last April in Limerick,” says Fr Eamonn Fitzgibbon, the synod coordinator, who is now director of the Institute of Pastoral Studies at Mary Immaculate College.

“One of the strongly expressed wishes that came out of it was that we would somehow connect liturgy with ordinary folk, and that a lot of our liturgy and prayer would be delivered by ordinary folk,” he says, continuing: “We can see that that’s clearly a need now with the declining number of clergy and the availability of clergy and religious to lead prayer, as has been traditionally done in Ireland. So we’re looking at the whole area of lay people leading prayer and liturgy in their own parish communities.”

Describing the April 25 liturgies as “the first step”, he says. “Down the road people in parish communities will give a commitment to be involved in leading public prayer, that might include things like receiving remains over the extended period of a funeral, it might include at other times when clergy are unavailable leading prayer in nursing homes – all those kind of moments which traditionally would have been led by clergy would now be led by lay people.”

Skills

Noirín Lynch from the Diocesan Pastoral Centre has already been involved in training a group of 90 lay people from around the diocese in this, he says, with her also studying in Maynooth to develop her skills in this area.

“A lot of our pastoral plan is on building capacity at diocesan level, making sure that someone like Noirín is trained up and qualified and competent at diocesan level but then at local level building capacity by training people at local level to do this sort of thing so they are competent and confident to lead prayer and bring people together,” Fr Eamonn says.

The first day’s training started with emphasising the centrality of Sunday to the Church, Noirín explains, before considering the role of weekday prayer on behalf of the whole community, looking then at the areas of ritual, prayer, and liturgy.

“Then we went through some templates of what might Morning Prayer look like if we used it, what would a liturgy of the Word look like if we used it. That brought up loads of questions for people. They loved the experience of Morning Prayer, and then went ‘Obviously we’d receive Communion,’ and I asked ‘What if that wasn’t possible? Let’s talk about that.’”

There can be a tendency to think of the Mass as the only real form of public prayer, says Fr Eamonn, pointing out that, “the Eucharist is the source and the summit and the fulfilment, but Sunday really is the day that we need to be focused on, and during the week we could explore the whole range of possibilities.

“I think in Ireland we have become very narrow in our understanding of community prayer and liturgy, that it’s almost as if it’s the Mass and only the Mass,” he says, adding, “I’m often reminded of that famous line from Father Ted, ‘Is there anything to be said for another Mass?’”

Certainly how our parishes will cope as our clergy numbers decline is an increasingly pressing issue, and weekday Masses look like an obvious casualty of this, but the question is whether Communion services are a plausible solution.

Spiritan missionary Tom Whelan, who teaches at the National Centre for Liturgy in Maynooth and is visiting professor of theology in Trinity College Dublin says that, “while Sunday Eucharist is obligatory from a faith point of view, because Sunday is the day of the Resurrection so that Christians always gather on a Sunday, weekday Eucharist is optional and devotional”.

Viewed in terms of the Church’s history, the notion of ordinary parishioners receiving Communion on a daily basis is a recent development, he says. “This is not a popular thing to say at all, but the reality of parishes everywhere as a norm having daily Eucharist is no older than approximately 150-160 years or so.”

Traditional form

Noting that there have always been exceptions in cathedrals and monasteries, he says that through most of the Catholic world: “The idea of people having a daily Eucharist is taken to be an unbelievable privilege that is incredibly rare, except in cities. In these places whatever happens on weekdays is that people have some form of Liturgy of the Hours, or Daily Prayer – Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, and it’s normally not necessarily the version of Evening Prayer that clergy might pray. It would be a much more traditional form, that lay people could lead themselves.”

Recalling how the Liturgy of the Hours dates back to the Church’s early history and is the traditional daily prayer of the Church, Tom admits that it would have been rare – if it happened at all – for entire parishes to gather to pray the Office in this way, but says, “when we move away from a sense of individualism in prayer – saying ‘I’m going off now for my Mass’ – and when you look at the corporate, it means that you are able to make the accurate statement that our parish prays every day. Now, maybe Mrs Murphy or Mr O’Brien can’t be there, but it’s still the parish that’s praying.”

Keen that simple versions of Daily Prayer should become more common, he says Ireland’s vocational decline is hardly grounds to turn to Communion services to replace regular Masses, observing: “Countries like ourselves complain about lack of vocations, but proportionately compared to other places, priests are still tripping over each other here.”

Fr Eamonn tends to agree. “Do we look at distributing Communion as part of a lay-led liturgy – a Communion service?” he asks.

“Particularly in America, there’s been a move away from that, because while that had been the practice for many years, they found that over the course of many years it created confusion in the minds of people between what is Mass and what is not Mass.

“Also it can indicate a poor enough theology of the Eucharist, in the sense that Eucharist is meant to be an action – we take, we break, we share – but [in Communion services] the Eucharist can become an object rather than an action.”

Closed question

Stressing that this isn’t “a closed question”, Fr Eamonn says, “these are things we’ve to be mindful of and we’re conscious that we want to do it right when we set into this kind of territory”.

While theologically matters may seem cut and dried, says Fr Tom, things can be different on the ground. “I’m speaking from the persepctive of theology – I appreciate fully that there are pastoral questions that come up here, and how this is dealt with in a pastoral context is slightly different from the cleaner profiles that theology might propose,” he says.

Creativity will be needed in terms of what speaks to people and connects with their lives, says Fr Eamonn. “The challenge is we also have people who are very committed to the Eucharist and wish to receive Communion and we need to honour that. We need to be respectful of that, so whatever happens it needs to be done sensitively and carefully. We need to be very mindful of the pastoral reality on the ground.

Commitment

“There’s no point in a dictat coming from on high, saying this is how we’re going to do things and we’re going to make you like it whether you like it or not – that can’t happen.”

Many of Ireland’s daily Massgoers have a profound commitment to the Eucharist and to receiving Communion, he says, so it can be difficult for them to understand why, if they’re gathering, they cannot receive.

There can be a real sense of loss around this issue, says Noirín, explaining, “people are used to the opportunity of daily Mass and when there isn’t that possibility, it raises the question of how do we celebrate on weekdays”.

She agrees with Fr Eamonn in emphasising the necessary distinction between Sunday as core day and weekdays as days when the community comes together to pray. The question is what form their gatherings should take: should they be liturgies of the Word – with or without Communion services – or should they be versions of the Morning Prayer of the Church?

“One of the things in the Second Vatican Council that was very strong was that they used the image of the table of the Word, not just the table of the Eucharist,” says Fr Eamonn, “We never really broke that open, we never really managed to create that sense that the Word too is something that nourishes us and brings us life, where Jesus is present, and how do we create a sense among ourselves of the table of the Word being as important and as valued as the table of the Eucharist. There’s a challenge there.”

He notes that “the priority is about keeping the community together to pray and worship regardless of whether or not a priest is available to them”, and Noirín says: “There’s also another conversation about the parish being the faith community where people gather. Sometimes you say what’s most important is Mass, and people can get into their car and drive somewhere, but then what happens to the sense of community and praying on behalf of the people of God?

“When people gather on a weekday morning, they’re not just gathering for the 15 people who are there,” she continues, “when we gather for liturgy, the official Prayer of the Church, we don’t gather for ourselves alone. Our prayer includes all the people of the parish and beyond. It’s about the parish seeing itself as a faith community, not simply a service where Father comes out and serves, but that actually the parish is alive.”

The challenge, then, is to empower people, to give the laity the kind of role that the Council envisaged them having and that Limerick’s synod sought to recall.

Tom thinks that one useful way of promoting the Liturgy of the Hours in parishes would be for priests to join parishioners in this where possible, not taking over leadership but simply praying alongside the people. “It would be a very small but important way of giving that a bit of status,” he says.

This isn’t the first time Limerick has tried to promote lay leadership, Noirín says, noting: “We did this 10 or 15 years ago and people did the training, but though people thought it was a nice idea they didn’t feel there was a need,” she said, adding people now realise that “we’re in a different time”.

After the first training day, she says, participants were urged to go home to reflect and discuss things with their priests. “Priests are the liturgy leaders in the parish, so if you’re going to be leading liturgy or public prayer, you’re going to be with them preparing that – it’s going to be very much about the whole parish together, not about being separate,” she says.

The participants will meet again on April 1 to look at practical resources for lay-led liturgies, very practically walking through what’s involved in leading liturgies, fitting with Scripture, and how the liturgies of the Word can be prepared for and the Gospel reflected upon so, for instance, Prayers of the Faithful come from prayerful reflection on Scripture, not merely our own thoughts.

A third meeting will follow in which participants reflect on their experience of lay-led liturgy, she says, and look to the future. “What we really want is that in every parish, people will say what is the need for public prayer now, so some parishes will say we have a daily Mass, but we don’t have anyone to go to funeral homes or to pray with people in their homes when they’re waking a family member, or they have a nursing home and they’re not able to offer daily Mass there, but we could go down maybe twice a week and offer a prayer service,” she says.

Ultimately, this is all building for the future, says Fr Eamonn. “Any of this now is looking towards the long term, towards the future, 10, 15, 20 years down the road, so these are kind of initial tentative steps, a new way of doing things that will evolve and develop and we’ll see lay people taking on greater roles and far more responsibility in terms of all of that world of liturgy.”

Lots of parishioners already have the ability to lead parish liturgies, Noirín notes, but lack the confidence to do so, so the training aims to tackle the issue of whether parishes feel capable of gathering together in prayer in the absence of a priest – it shouldn’t be the case, she says, that a parish says “when we needed to gather and pray, we didn’t have the confidence to do it”.

“It’s about giving people resources and skills so that when we need to gather and pray, if a priest isn’t available to lead us, that we’re able to do that, always saying that it comes back to Sunday Mass at the heart of where we are, and that we would hope that we would have daily Mass where possible, but that we would never say that we don’t know how to gather,” she says.

It’s about trying to build community, she says, saying that imagination will be needed to do this, as well as more focus on the theology of the Eucharist. “What we really need is probably a general catechesis around Eucharist not being simply reception. There’s the piece that when we gather, we are part of an action, that God is acting, transforming us. That whole Eucharistic prayer is fundamental. If you lose that sense of what Eucharist is, it becomes a sort of private devotion in public,” she cautions.

Communicants

While noting how warmly people respond to the Liturgy of the Hours when introduced to it, she is keen to stress that the feelings of daily communicants need to be respected at a time when weekday Masses will be become less and less frequent.

“People are grieving a loss, it’s a relationship and how they relate and connect with Jesus Christ in their daily lives, so sometimes it can sound like people talking about rights, but actually what we have to do is explore how the Word could be as nourishing as Eucharist, but not to just jump in and say ‘you should know this’,” she says.

“It’s about journeying together,” she says, continuing: “In practice we’re bringing people from a place to somewhere and the pastoral journey is quite important. If we miss the journey we could lose people who’ve been with us always. It’s a duty of care really to people who are our core, and are gathering every day to pray for us.”

Greg Daly

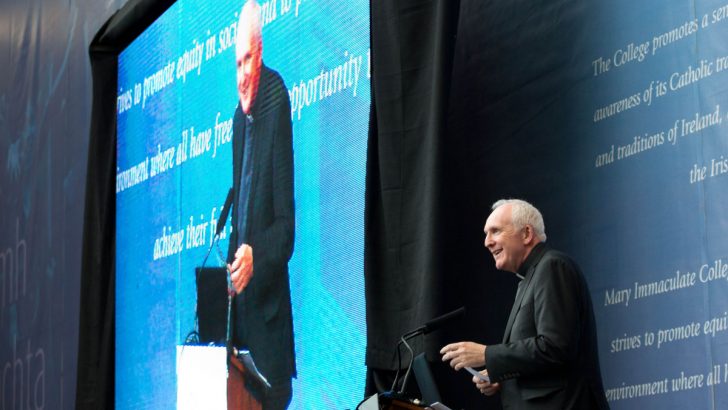

Greg Daly Bishop Brendan Leahy attending The Limerick Diocesan Synod, the first in Limerick in over 80 years and the first in Ireland in half a century. The Synod has been officially blessed by Pope Francis. 400 delegates will discuss 100 proposals, formed after an extensive 18 month process at Mary Immaculate College.

. Picture: Sean Curtin FusionShooters.

Bishop Brendan Leahy attending The Limerick Diocesan Synod, the first in Limerick in over 80 years and the first in Ireland in half a century. The Synod has been officially blessed by Pope Francis. 400 delegates will discuss 100 proposals, formed after an extensive 18 month process at Mary Immaculate College.

. Picture: Sean Curtin FusionShooters.