Irish people, as we all know, have a great grá for local legends, indeed any kind of local lore.

In the poetry of W. B. Yeats, Queen Maeve, though supposedly buried on the frowning peak of Knocknarea, might be still a living person. Yeats deep interiorisation of old traditions of a locality is not unique.

When Thomas Kinsella published his translation of the Táin, enhanced as it was by some of the best illustrative work of Louis Le Broquay in 1969, he was also able to produce a map, of the events of the epic as they played out on the Cooley peninsula.

It was a striking example of the integration of tradition and landscape. It was striking too that the nearest parallel culture in modern times to the Gaelic Irish was not so much with ancient Greece, as Prof. Ridgeway and so many others claimed, but with the Amazulus of South Africa, their kingdom also being dominated by the violence of a warrior class, insane personal pride, and by cattle raids.

All over Ireland local legends have become attached, for instance, to neolithic megalithic monuments, the ‘Beds of Diarmuid and Grainne’, built many thousands of years before there were any Gaels in Ireland. These ancient monuments were simply appropriated.

But this may happen more often that we think. We tend to associate King Arthur and the Arthurian mythos with the English West Country and parts of Wales. Whoever he may have been in history, King Arthur belongs in some mysterious way to Tintagel and Glastonbury.

Surprise

It is something of a surprise then on travelling round Brittany to find large parts of the tales of Arthur, Merlin, Morgana Le Fey, and Tristan moved bodily to that country and to be associated with landmarks and districts there.

Merlin, for instance, is now associated with the Forest of Brocéliande, and King Mark and his court, not with Castle Dor near Fowey, but with the Penmarch peninsula. Again an entire saga has been appropriated, or rather simply carried into the landscape of Amorica by the Britons who fled from the Anglo-Saxons and soon became the Bretons.

Nearer home, however, we can catch the same sort of things happening today.

In 1860, in a moment of professional crisis, Dion Boucicault fell under the spell of Gerald Griffins’ novel The Collegians (1829), based on the murder of Ellen O’Hanlon in 1819 – he had reported the trial of the murderer. But Boucicault not only moved the scene of the action to Killarney (then becoming popular with tourists), and sentimentalised the plot. Julius Benedict, in adapting the play for his opera The Lily of Killarney (1862) further changed the plot.

On a visit to Killarney a while ago, my wife and I inquired in the tourist office about the more unusual things to be seen in the neighbourhood. The young lady dealing with us was anxious to please. Among the things she suggested was a visit to the ‘Colleen Bawn rock and caves’ (as seen in Act II, scene 5).

Natural pedant that I am, I replied that the tragic tale of the murder of Ellen O’Hanlon had nothing to do with Killarney. But as far as she was concerned, the Colleen Brawn was an historical person who truly belonged to Killarney.

A guide book of 1861 makes no reference to the play; though by that time photographs of the Colleen Bawn Caves under the Coleen Bawn Rock were on sale. However, another guide of 1926 finds the Coleen Bawn well to the fore as Killarney’s appeal. And Danny Mann’s, an eatery named for the murderous henchman of the villainous Creggan in the play, still thrives in the town.

But our encounter with the lady in the tourist office suggests the plot of the play and opera has now become itself an accepted local legend, a sort of modern version of the Beds of Diarmuid and Grainne.

All this makes one wonder though about Queen Maeve and the Brown Bull of Cooley. Were they too originally brought from elsewhere by the Gaelic invaders who carried continental Celtic culture to Ireland?

Was their home originally to be found in cattle pastures of Celtic Switzerland about 500 years before Christ? Now there is food for thought!

Peter Costello

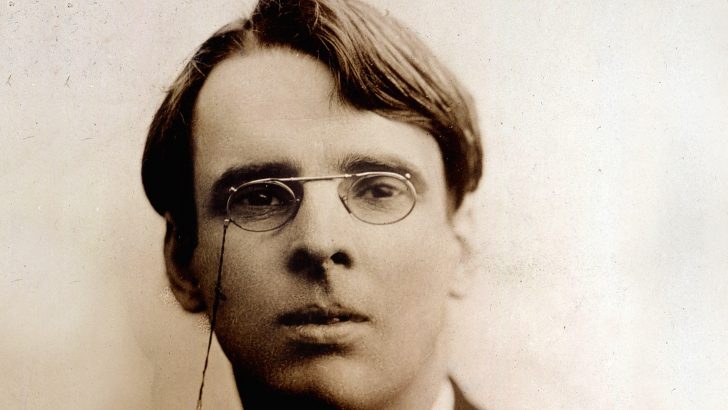

Peter Costello WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS (1865-1939).

Irish poet and dramatist photographed c1900.

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS (1865-1939).

Irish poet and dramatist photographed c1900.