Dublin prides itself of being “a city of literature” – there are UNESCO signs all over the place promoting the fact. But when we look back over the centuries we can see that the city’s true life in literature only begins with Jonathan Swift, the 350th anniversary of whose birth we are celebrating this year.

But this is strange. Historians claim Dublin was ‘founded’ by the Vikings in 841. Of course, there is a minority who say this is only because it was then that a walled city was created.

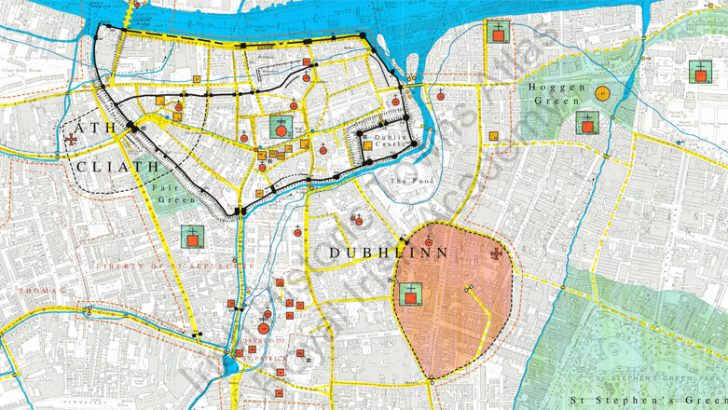

But before then the religious houses, churches, and settlements such as the Hurdleford and The Blackpool, were so to speak a city en blé, though one very different from the Roman idea of an urbs or the oppida of the Continental Celts. The Irish Gaels did not do cities, but the extensive townland of pre-Viking Dublin might easily be mistaken for one.

But where, it might well be asked, is the literature of this early city and its medieval successor? – literature that is in the shape of works that might be still readable. Leaving aside annals and sagas there is really nothing.

Later it is said that there was an Gaelic speaking community inside the medieval and Georgian city of Dublin, but where are the poems and tales of that urban life? Nowhere.

This being the case it very strange that Irish writers and scholars ignore almost completely the fact that from at least the 6th Century Dublin had had a celebrated place in the imaginative literature of Europe.

I am referring to the Romance of Tristan and Isolde, from which one of Wagner’s most important operas was derived in 1865. It is regarded as one of the great tragic tales of world of literature.

It will be recalled that though Tristan himself was born in Lyonness, that lost land that once lay between Land’s End and the Scilly islands. He kills the knight sent by King Gormund of Ireland – or rather Leinster alone – to claim a tribute from Cornwall. But he sustains a wound and goes to Ireland to have it cured. He meets the king’s beautiful daughter Isolde. Later he returns to ask for her hand in marriage, not for himself, but for his uncle King Mark.

However, as the opera relates, by way of a magic potion Isolde and Tristan fall deeply in love. The tale may untimely be a retelling of the ancient legend of Diarmuid and Grainne, but with different historical figures, for there is little doubt that the characters of the romance are indeed historical.

Interaction

King Mark certainly is. A memorial stone to Tristan naming them both can be seen today near the entrance to Menabilly, once the home of the Daphne Du Maurier. Mark, from his interaction with St Sampson and St Pól Aurelian, a missionary in Brittany, can be dated to the first decades of the 6th Century AD (say 500-525).

So was the beautiful Isolde also a real person in the Dublin region of that time? She reputedly gave her name to the little village of Chapelizod; but the actual church connected with her name was not there, but at the top of Mill Lane behind Stewart’s Hospital, on the other side of the Liffey (though still in the historical parish of Chapelizod). This edifice is recorded (in The Book of Howth) as dating from 519.

This congruence of dates – and there are others – suggest that there is an historical reality behind the story.

Originally the tale would have been orally transmitted to poets in Wales and Cornwall. The name of King Gormund comes from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s strange work The History of the Kings of Britain. With the additions, the romance as whole was elaborated by Norman-French poets on the basis of an early version by a Cornish or Breton poet familiar with Cornwall.

Not all these poems survive in complete form. But in Gottfried von Strassburg’s version (c. 1200) the Dublin region is continually evoked in connection with Isolde. This was one of the most popular and widespread literary works of the middle ages. And yet Dublin seems blind to the fact.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello