The idea of indulgences has profoundly biblical roots, Greg Daly writes.

One of the Reformation’s greatest ruptures was its transformation of how Christians saw relations between the living and the dead: for those who embraced the ideas of Luther and the other Reformers, it was no longer possible to ask the saints in Heaven to pray for them, while there would be no point in praying for the souls of the dead.

Partly this was, of course, because the very idea of Purgatory as a final place of purification had been dismissed as unbiblical, its implicit scriptural roots ignored, rejected, or even cut away. Partly too, however, it lay in a denial that the Catholic belief in the ‘Treasury of Merit’, through which the good works of Christians and above all Christ himself could be employed to help others, was in any sense biblical.

For Gary Anderson, Hesburgh Professor of Catholic Theology at the University of Notre Dame, and author of Sin: A History and Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition, claims to this effect can hardly be further off the mark.

“The notion of a treasury of merits is found both in Rabbinic Judaism and in early Christianity,” he says. “They didn’t borrow it one from the other so how do both of them have this idea if it’s not biblical?”

The origins of this “deeply biblical” idea lie, he says, in such Second Temple Jewish Scriptures as the books of Tobit and Ben Sira, the latter perhaps better known as Sirach or Ecclesiasticus – which were excluded from the Bible by Martin Luther and other Reformers.

Claiming that the after-effects of this idea are strewn throughout the New Testament, Prof. Anderson says that especially since the Enlightenment, “There has been a deep ‘forgetting’ of the scriptural origins and the prominence of this motif in Christianity.”

Metaphor

However, he says, “when one moves from the vault of the Hebrew bible itself to the Hebrew of the second temple period and the Aramaic of the second Temple period – in other words the mother tongue of Jesus – the dominant metaphor for sin, culpability etc is sin as a debt, which is obvious from the Lord’s Prayer”.

Jesus doesn’t say “forgive us our debts” in the Our Father for no reason or as a metaphor he made up on the spot, Prof. Anderson explains: he’s simply reproducing the way he spoke on an everyday basis.

“As soon as you have this notion that sin is a debt, then virtuous activities are thought to be a counter-balance to that and they’re accrued as merits or credits,” he says. “The question then is where do they accrue? Where do the debts accrue? In Heaven?”

A key text underpinning this conceit in early Rabbinic Judaism and early Christianity was Proverbs 10:2, he says, which was read in the New Testament period as contrasting earthly treasuries with treasuries funded by charity that deliver one from death. This set up an opposition, he points out, between acquiring earthly wealth and acquiring heavenly wealth.

“Earthly wealth was useless. That’s why Jesus tells the rich young man in that famous parable in the New Testament that if he wants eternal life he needs to give his wealth to the poor, then he’ll have a treasury in heaven, then to come and follow him.

“That comes right out of the theology of this proverb,” he says, pointing also to the parable of the Rich Fool in Luke 12:13-21, which likewise contrasts earthly and heavenly riches, warning against hoarding the former and urging an effort to become rich in God’s eyes, which was done, it was believed in New Testament times, through charity to the poor.

“It’s deeply biblical, it’s all built on the proverb that I just mentioned, especially the way it’s read in the book of Tobit and Ben Sira, and the treasury of merits follows from that,” he continues, explaining: “The treasury of merits is nothing other than those treasuries that are the result of one good work and not generally any good work: for the Church the good work was particularly giving your money to the poor.”

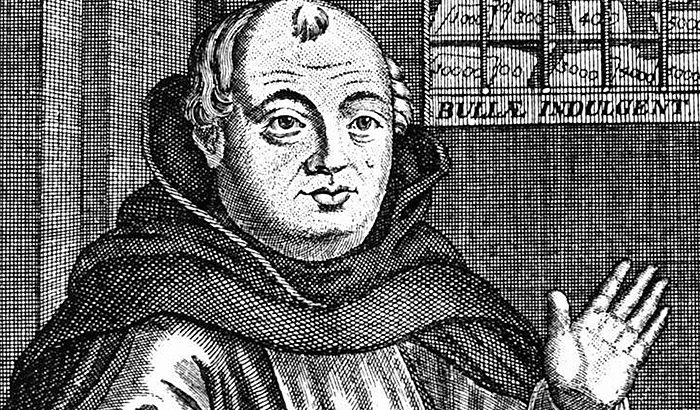

When Luther published his 95 theses, Prof. Anderson says, his concern was not with indulgences in themselves. “What he doesn’t like is the Pope’s proposal that funding the restoration of St Peters is going to count whereas for Luther what counted was giving the money to the poor.

“That’s the beef he has with Rome,” he stresses, “building what will be one of the most spectacular buildings in the Western world over the next 100 years for Luther is at variance with the traditional way that the Church has understood the accumulation of a divine treasury.”

For the early Church, the Treasury of Merits was based on those specific actions that involved good deeds for the poor, and upon which our eternal salvation rested. The separation of the sheep and goats in the Last Judgment scene of Matthew 25 clearly maps out the importance of this, he says.

Much of this has been sidelined in the modern world, he observes, pointing out that the important concepts of altruism and social justice have obscured the foundational Christian call to imitate Christ. The exclusion of the books of Tobit and Ben Sira from Protestant Bibles and theology have further driven out this concept, removing the underpinnings from key New Testament passages.

In Luther’s day, indulgences could be sold, and while there were abuses in this, the process wasn’t in itself quite as mechanical or cynical as often portrayed. “One gave money to the poor because it was good in and of itself,” Prof. Anderson says, explaining how the Church believed it could draw down from the Treasury of Merits to help those who had helped the poor. “It was the way in which the Church helped the poor, and the Church was happy for you to do such and as repayment for such they’d they’d give you 50 years off purgatory.”

Unmerited love

Even a few years ago, Pope Benedict XVI in his encyclical Deus Caritas Est (‘God is love’) expressed concerns about an ethics that would completely separate an unmerited love for the other with one that benefits the self.

“The reason why I as an individual will benefit from helping the poor isn’t so much that God has put that reward in place to encourage me to do such but rather the reason why I benefit is that is how the universe is made,” Prof. Anderson explains, recalling how in Dante’s Divine Comedy, charity is what moves the stars.

“For modern readers that just sounds like a poetic nicety but Dante really believed that, he really thought that love was a governing agency within the world,” he says.

Our post-Reformation disenchanted world can seem a mechanical universe of impersonal forces, where love is simply an accidental thing that happens between two persons, but the pre-modern world view was completely different.

“The world was driven by love and it was incumbent upon the Church to instruct people about it,” says, continuing, “the world doesn’t look that way but that is in fact how it is. So, that’s why I benefit from acting charitably, because I’m tapping into the very way the world is organised.”

Greg Daly

Greg Daly