Ireland’s Hidden Medicine: An exploration of Irish indigenous medicine from legend and myth to the present day by Rosarie Kingston (Aeon Books, €19.99/£16.99)

This book will be compelling reading for those interested in folk medicine, also known as indigenous or traditional medicine. Such ideas are an important part of our heritage, for some of these ideas must predate the Celtic invasion in 300BC, and come down from much earlier times by word of mouth.

Division

At the outset the author divides medicine into biomedicine and indigenous medicine. The former is based on the scientific study of the human body’s biological system. The latter is the term to describe the range of healing methods used by any indigenous community which are transmitted orally from generation to generation and are coloured by local beliefs and the environment. The conduct of this folk medicine in Ireland can involve plant medicine, physical manipulation and charms, prayers, rituals and practices known as piseogs (superstitions).

In an early chapter, Rosarie Kingston provides a history of folk medicine in Ireland from Pre-Christian times to the present. One of the legendary peoples of Ireland were the Tuatha De Dannan and their God of health was Déin Chécht. Two of his children were herbal physicians and surgeons.

Legends

The legends, which featured the Red Branch Knights, record those wounded in battle being plunged into medical herbal baths. Lebor Gabála Arenn, the origin story of the Irish people, describes a hospital near the present-day Armagh City. The arrival of the Christian missionaries in the fifth century introduced a whole new raft of folk medicine associated with relics, pilgrimages, prayers, rituals, blessings and holy water.

The scientific age, which was ushered in by Galileo, Descartes, Bacon and others, marked the beginning of a radical decline in a belief or interest in folk medicine. That trend has continued into the digital age. Hence folk medicine is today for the most part confined to rural districts in just a few parts of the country.

Today in Ireland a practitioner of folk medicine is generally known as a ‘person with a cure’. He or she may have a cure for eczema, TB, skin-cancer or a haemorrhage. Belonging to a particular family, their ‘gift’ is handed on from one generation to another. The different types of cures they purport to provide can be classified into plant medicine, physical manipulation and charms, prayer and rituals.

Many ‘healers’ have ‘a bottle’. This will contain specific plants, about which the healer is very secretive, and can be applied or taken. The most popular practice in the Irish healing tradition is that of physical manipulation.

Some of those engaged in either physical manipulation or administering the bottle seem to have had extraordinary success. One such person was Séan Boylan, onetime coach of the Meath Senior Football Team. The third area of folk medicine is that of charms, prayers and rituals. Their efficacy, of course, lies in their placebo effect.

Famine

The author describes the negative effect the Famine, the National School system of primary education and the Catholic Church had on folk medicine.

She also charts how economic progress and upward social mobility turned people away from folk medicine because of its association with the peasant culture of the past.

In today’s scientific and technological-orientated world there is little room for folk-medicine. Thus those who practise biomedicine (real medicine) regard folk-medicine as at best to be merely inconsequential. However, as is indicated in this book, the services folk medicine can provide, and has provided in the past, are not to be lightly dismissed.

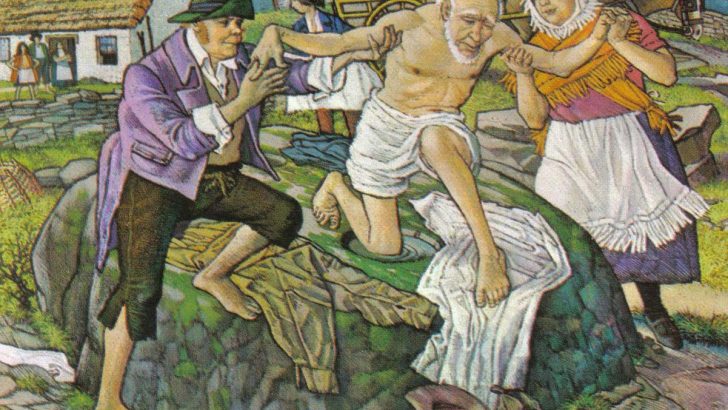

Bullaun cure.

Bullaun cure.