Tribute to a statesman

Perhaps his greatest achievements were reforms around policing and justice, writes Martin Mansergh

Seamus Mallon played an indispensable role in the SDLP as deputy leader of that party, of which he was part of the bedrock in deeply dangerous times. In later years, he received a great deal of respect for the values that he steadfastly represented and upheld, no matter what the setbacks, as a peaceful and democratic alternative to the costly path of violence.

The SDLP, founded in 1971, grew out of the moderate and reformist main stream of the civil rights movement. While it is acknowledged that Northern Ireland in the 50 years of one-party rule was ‘a cold house for Catholics’, what is not mentioned is the corollary, that this would encourage them to go elsewhere.

The situation, whereby any political or administrative discretion was habitually used to advantage members of the unionist community, did achieve the result that the Catholic and nationalist community remained a static 35% of the population.

The provisions of the post-war British welfare state by-passing the electoral, housing and employment discrimination strengthened that community, of which Seamus Mallon, as a principal teacher in Mullaghbrack Primary School in Armagh, was a leader. The unionist hegemony was not vulnerable to onslaughts on partition, whether political or paramilitary. It became vulnerable on the denial of civil rights.

Equality

The establishment of civil rights on a basis of equality, on which some immediate advance was achieved but where after that progress was slower, is a legacy to which the SDLP and Seamus Mallon greatly contributed. The high moment of hope was the Sunningdale Agreement, which created a power-sharing government with an Irish dimension in the form of the Council of Ireland. Some unionists and commentators blamed its collapse on the Council of Ireland being a bridge too far.

Seamus Mallon was convinced that this excuse was just a plausible cover for resistance to power-sharing. Much of the next two decades were spent by the SDLP refusing British efforts to coax them away from power-sharing and an Irish dimension as their requirements for a settlement. The top British civil servant in Northern Ireland, Frank Cooper, according to Mr Mallon, told them: “We will starve you out.” Indeed, Mr Mallon and some other SDLP members were often short of paid employment, and dependent on the earnings of their spouse.

Fulfilment of his life’s work came with implementation of the Patten report creating the Police Service of Northern Ireland,”

Seamus Mallon and his wife Gertrude lived in the mainly Protestant village of Markethill in Armagh, a county which was an epicentre of the Troubles, and where they faced hostility from both loyalist and republican paramilitaries. He believed he was next on the death list, after Miriam Daly and John Turnley were assassinated by loyalists in 1980.

His parliamentary assistant based in Newry, John Fee, nephew of Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich, was beaten up in 1994, after he criticised the IRA. Tragedy struck not just the community, but close personal friends from both sides of the divide. Parties like the SDLP were sometimes caught in the middle, for example, during the tensions of the 1981 Hunger Strike when the British government of Margaret Thatcher and the republican movement were both determined to face the other down.

In May 1982, Seamus Mallon was nominated to the Seanad, along with John Robb. It set a precedent for later nominations of northerners. His brief membership of the Seanad led to him forfeiting his seat in the Northern Ireland Assembly through unionist court action. The New Ireland Forum of 1983-4 gave the SDLP an alternative, and the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement created a channel for nationalist grievances through the Maryfield Secretariat.

Mr Mallon opted to stay with his party over the agreement, which involved a rupture with Charles Haughey. In 1986, he won a Westminster seat, which he held for 20 years.

The political issue that Mr Mallon most concentrated on was policing, security, and the judicial system. He attacked notorious instances of state collusion, ‘supergrass’ trials, and shoot-to-kill incidents, but not justifying IRA attacks on the police.

Fulfilment of his life’s work came with implementation of the Patten report creating the Police Service of Northern Ireland, in which he firmly resisted British attempts to dilute its recommendations. Even though it cost his party, the timing of SDLP support for policing was ripe.

He famously described the agreement as ‘Sunningdale for slow learners’”

Seamus Mallon had reservations about the Hume-Adams dialogue and the effect it might have on the future of the SDLP, forebodings that seemed to be borne out until recently. The SDLP deserve much of the credit for the institutional framework of the Good Friday Agreement that had been worked on in dialogue with unionists in the early 1990s in the Brooke/Mayhew talks.

Seamus Mallon famously described the agreement as “Sunningdale for slow learners”, a barb directed both at the republican movement and the unionist parties. Seamus Mallon pioneered the role of deputy First Minister and showed that the executive could work. He had a difficult relationship with the First Minister David Trimble.

The early years were bedeviled by political instability caused by the long stalemate over IRA decommissioning and Sinn Féin support for a reformed police force.

When John Hume and Mr Mallon retired, Sinn Féin overtook the SDLP.

Mr Mallon complained that the two governments had deliberately decided to back Sinn Féin over the SDLP. Sinn Féin certainly exploited the fact that their consent on weapons decommissioning and support for policing was hard to obtain.

At the end of his life, the SDLP made a come-back in the December 2019 British general election. He became greatly concerned about aggressive political pressure for a border poll that would stoke up tensions, without any hard evidence of a majority in Northern Ireland for unity post-Brexit.

Neither of the two large parties in the Republic is prepared to go down a path, that like the anti-partition campaign could be totally counter-productive.

In his recent memoir A Shared Home Place, a chapter is devoted to his thoughts on religion. In it, Mr Mallon wrote “my Catholic Faith is what I go to when I am in difficulty”, and how it was particularly needed by them both during the long illness of his wife Gertrude.

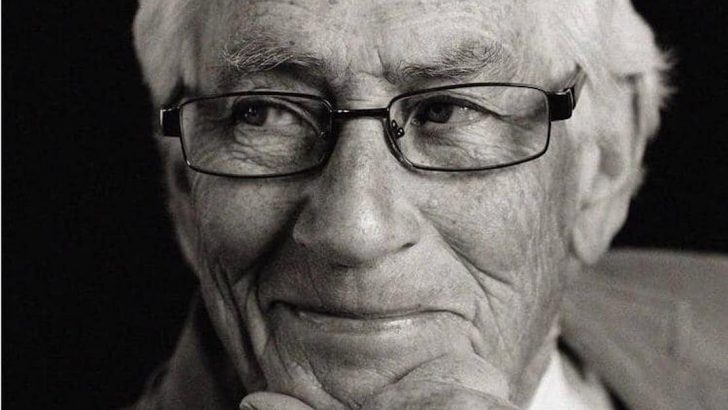

The late Seamus Mallon

photo: armaghi.com

The late Seamus Mallon

photo: armaghi.com