An Irish Food Story

by JP McMahon

(Nine Bean Rows Press, €25.00 / £20.75)

Irish Food History: A Companion,

by Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire, Dorothy Cashman and others

(Royal Irish Academy, €45.00 / £38.00)

This holiday season of feasting and drinking, quite in the ancient fashion of the Fianna some might say, seems to be a good time to give some thought, glancing back over all too human activity of eating, or perhaps more scientifically, food consumption in Ireland.

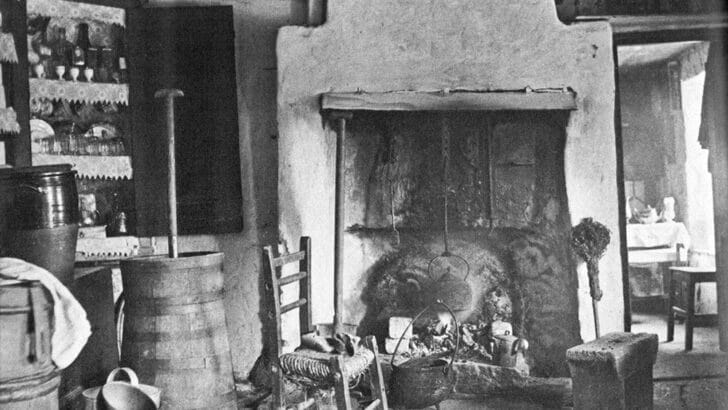

All too often many Irish people in doing so seem to invoke scene of famine and hardship. But the truth is very different, Irish history was, on the whole, a matter more of feast rather than famine.

However, the trouble these days is that much Irish food is not Irish at all. A walk around a supermarket will reveal the huge proportion of food we import. We should eat, some say, only what can be reared or grown within 20 miles of our home.

Yet the best land for markets gardening, for growing all kinds of vegetables, lying to the north of Dublin, has been built over in the last quarter century or so, all in the name of development. An old fashioned moralist, of the kind now in short supply, would have called this a sin.

So Irish food is deeply problematic. The first of these books is an accessible easy read about amusing or interesting aspects of Irish eating and cooking.

Gourmet

But it is, as is so often the case these days, written by a professional cook. Whatever became of those teachers of “domestic science” who encouraged for boys and girls skills of home cooking, all those dedicated users of All in the Cooking.

Instead of a welcoming dinner, home cooks are now encouraged to eat every day like a gourmet, whatever the pain and cost. This book will not meet the real needs of real people, it belongs in foodie fantasy land. In reality we live in a land were some 700 dinners and 350 breakfasts are provided every in the Capuchin Day centre in Bow Street, not to forget the Little Flower Penny Dinners in Dublin, and the Penny Dinners down in Cork and other groups all over Ireland.

I suppose we should be cheered in some obscure way that this once famine ridden land can now taken such extravagance in its stride”

The second book comes from the press of the Royal Irish Academy. It runs to nearly 800 pages and is written by some thirty odd contributors, surveying in magisterial manner eating in Ireland since the earliest days of human culture here.

It seems that most of the 2500 copies printed have been already sold, at a price of €45.00 – which isn’t so much really, much being only a third of so of what a review in a certain newspaper of record would pay for a meal for two in the latest restaurant in vogue.

I suppose we should be cheered in some obscure way that this once famine ridden land can now taken such extravagance in its stride.

Famine

The Famine was so disastrous because large areas of the west had become dependent on potatoes for their food source. The Inuit are said to have no one word for snow, but a multitude of names for its different forms. So to in Ireland there were 72 words for potatoes.

One has to pick and choose in a book this length in a short notice. I was fascinated by the chapter on Maura Laverty, an extraordinarily energetic woman who transformed life in the 1940s and 50s. But read to about the nature of Irish State dinning in the 20th century: a great contrast to home cooking, as much of it was supplied by the then famous restaurant in Dublin Airport, where many chose to have their wedding receptions.

The book rounds off with a chapter, as equally fascinating as that on Maura Laverty, about the life work, legend and heritage of Myrtle Allen down at Ballymaloe. But contrast this with what we know: that all too many families survive today on takeaway Italian piazzas, Indian curries and Chinese stir-fry, a striking indication of the changing nature of Irish society. But this cosmopolitan topic is not for this resolutely “Irish” focused book.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello