Normally none of us likes feeling sad, heavy, or depressed. Generally, we prefer sunshine to darkness, light-heartedness to melancholy. That’s why we tend to do everything we can to distract ourselves from melancholy, to keep heaviness and sadness at bay. Mostly, we run from feelings that sadden or frighten us.

For the most part, we think of melancholy and her children (sadness, gloom, nostalgia, loneliness, depression, restlessness, regret, feelings of loss, intimations of our own mortality, fear of the dark corners of our minds, and heaviness of soul) as negative. However, these feelings have a positive side and are meant to help put us in touch with our own soul.

Simply put, they help keep us in touch with those parts of our soul to which we are normally not attentive. Our souls are deep and complex, and trying to hear what they are saying involves listening to them inside of every mood within our lives, including, and sometimes especially, when we feel sad and out of sorts. In sadness and melancholy, the soul tells us things to which we are normally deaf. Hence, it’s important to examine the positive side of melancholy.

Unfortunately, today it is common to see sadness and heaviness of soul as a loss of health, as a loss of vitality, as an unhealthy condition; but that normally isn’t the case. For instance, in many medieval and Renaissance medical books, melancholy was seen as a gift to the soul, something that one needed to pass through at key points in life to come to more depth and empathy. This, of course, doesn’t refer to clinical depression, which is a true loss of health, but to multiple other depressions that draw us inward and downward.

Why do we need to pass through certain kinds of melancholy to come to a deeper maturity?

Insight

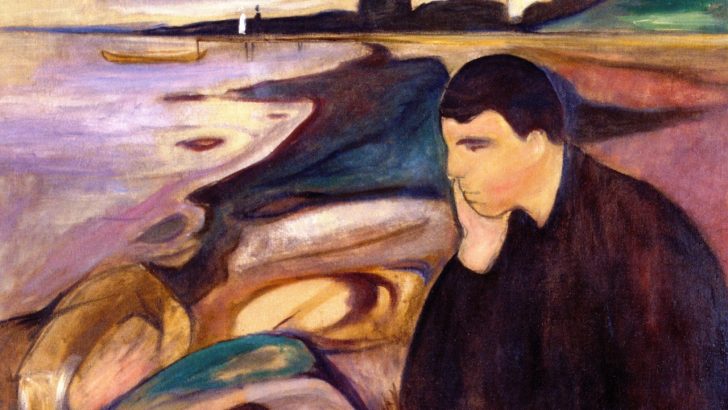

Thomas Moore, who writes with deep insight on how we need to listen more carefully to the impulses and needs of our souls, offers this insight: “Depression gives us valuable qualities that we need to be fully human. It gives us weight when we are too light about our lives. It offers a degree of gravitas. It also ages us so that we grow appropriately and don’t pretend to be younger than we are. It makes us grow up and gives us the range of human emotion and character that we need to deal with the seriousness of life. In classic Renaissance images found in old medical texts and collections of remedies, depression is depicted as an old person wearing a broad brimmed hat, in the shadows, holding his head in his hands.”

How can Good Friday be good if melancholy, sadness, and heaviness of soul are signs that there is something wrong with us?”

Milan Kundera, the Czech writer, in his classic novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, echoes what Moore says. His heroine, Teresa, struggles to be at peace with life when it’s not heavy, when there’s too much lightness, sunshine, and frivolity, when life is devoid of the type of anxiety that hints at darkness and mortality. Thus, she always feels the need for gravitas, for some heaviness that signals that life is more than the simple flourishing of good cheer and comfort. For her, lightness equates with superficiality.

Cultures

In many cultures, and indeed in all the great world religions, periods of melancholy and sadness are considered as necessary paths one must travel to deepen one’s understanding and come to empathy. Indeed, isn’t that part of the very essence of undergoing the Paschal Mystery within Christianity? Jesus, himself, when preparing to make the ultimate sacrifice for love, had to painfully accept that there was no path to the joy of Easter Sunday that didn’t involve the heaviness of Good Friday. How can Good Friday be good if melancholy, sadness, and heaviness of soul are signs that there is something wrong with us?

So how might we look at periods of sadness and heaviness in our lives? How might we deal with melancholy and her children?

First off, it’s important to see melancholy (whatever its form) as something normal and potentially healthy in our lives. Heaviness of soul is not necessarily an indication that there is something wrong inside us. Rather, most often, it’s the soul itself crying for our attention, asking to be heard, trying to ground us in some deeper way, and trying, as Moore puts it, to deepen us appropriately.

But for this to happen, we need to resist two opposite temptations, namely, to distract ourselves from the sadness or to indulge in it. We need to give melancholy its proper due, but only that. How do we do that? James Hillman gives us this advice: what to do with heaviness of soul? Put it into a suitcase and carry it with you. Keep it close, but contained; make sure it stays available, but don’t let it take you over.

That’s secular wording which can help us better understand Jesus’ challenge: If you wish to be my disciple, take up your cross every day and follow me.

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

Fr Ronald Rolheiser ‘Melancholy’ by

Edvard Munch

(National Gallery,

Oslo).

‘Melancholy’ by

Edvard Munch

(National Gallery,

Oslo).