Michael Healy 1873-1941: A Túr Gloine’s Stained Glass Pioneer, by David Caron (Four Courts Press, €55.00 / £50.00)

Back in October 1906, Robert Elliot in his pioneering book Art and Ireland lamented that so many churches in Ireland seemed to prefer to fill the windows of their churches with stained glass imported ready made from Europe, largely from Munich in Germany, a Catholic kingdom of the German Empire.

This was then true. Since the post-famine decades there had been a huge burst of Catholic church building all over the country. Irish clergy and their advisors chose the readymade, already admired glass, as an easy option. It was also comparatively cheaper to use German glass than trust, as the Irish clergy saw it, the vagaries of Irish artists and craftsmen.

So much so that St Brendan’s, the new Cathedral in Loughrea, influenced by the remarkable administrator of the day, Fr Jeremiah O’Donovan (the diocesan clergy’s choice in the diocese for bishop), was a showcase of Irish art of all kinds.

Some of the windows were by Michael Healy from a new firm he called An Túr Gloine (“The Tower of Glass”) in the manner of Irish myth. (I described the literary background to all this some years ago in one of my own books about the Irish literary revival).

Recluse

Michael Healy was a genius, but a recluse; a man and artist whose life was mysteriously vague. Now, however, at long last Dr Michael Carron has devoted a large, well researched and beautifully illustrated volume to the man, his career and his mysteries.

Dr David Caron studied at the National College of Art and Design, later returning there to lecture. He undertook a Masters degree in the United States, and a PhD in Trinity College, Dublin.

He was one of the three original compilers, along with Nicola Gordon Bowe and Michael Wynne, of the first edition of the important Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass, of which a new updated edition was issued a couple of years ago.

He observes that when Michael Healy died in 1941 only two people of importance wrote about him, the lawyer CP Curran and Thomas MacGreevy , the poet, critic and director of the National Gallery. It was as well they did, though they admitted they had never really been close to the man himself.

The heart of this book are long periods of research in which David Caron tracked down, annotated, recorded and had photographed Healy’s windows wherever he could find them.

The six-page list of locations alone is revealing of Healy’s work. The photography by Joseph Vrtiel is superb. The chapters of the book explore the shadowy life of the man and the course of his artistic development in exemplary detail.

There is no denying at this date the accomplishment of the artist. But what is of interest is to compare him with two other stained glass makers whose works have also been recently surveyed, Harry Clarke and Wilhelmena Geddes.

In Clarke’s work there is always a sense of fantasy that at times takes from the religious purpose of the windows, while Geddes’s people all seem to have an aspect of strong willed Ulster pride about them.

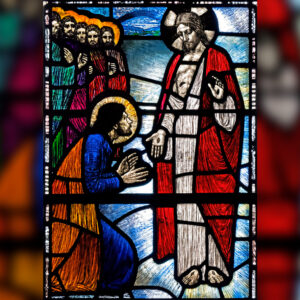

But Michael Healy’s work is not only exceptional, but deeply human too, Jesus, the saints, and the heroes, appear in a very human aspect. They are real people rather than merely imagined.

What a wonderful way to explore our churches and perhaps come to some understanding also of Ireland past and present. It is also a good reason to buy a copy of this book: for where there are windows by Michael Healy, there will be works by other artists as well.

Wander

Aside from his glass work Healy also loved to wander the streets of Dublin catching in his notebook rapid little sketches of people and street life that have an extraordinary fascination of their own.

I thought it a pity that David Carron could not give more space to Healy’s quick sketches and drawings done on the streets of Dublin, with which the artist was deeply familiar.

But very striking also are the translations of this kind of record into stained glass, as in the Emma Cons Memorial at the London Old Vic.

Of interest too are the oil on canvas Dublin landscapes, which I do not recollect ever seeing before, from a private collection. These open another aspect of Healy’s talent. They are calm and untroubled in a way the windows often are not.

Appreciation

I have long thought they would provide the ideal illustrations to a book about the real people of Joyce’s Dublin. But in reading this book and writing this appreciation a new idea came to me. These records of ordinary people, living out their lives, are an important, indeed essential complement to the work of an Túr Gloine.

For these people are the people who every Sunday, and in that era, other days of the week as well, crowded into the city church churches. These are Michael Healy’s essential audience, the very people and not the clergy indeed that these windows were really made for.

But this gave rise to another, more sobering thought. That the age of stained glass has come to an end. It is unlikely that many churches requiring them will be built in future.

The few churches built and most of the other public buildings now erected have little place for these kinds of windows. Lancet lights filled with abstract designs, perhaps, but no true windows in the older manner. The stream of books celebrating Irish stained glass artists are records of the past. We will never see their like again.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Detail of St Anne from St Peter and St Anne, with the Lamb of God (1907–8), Sacred Heart Catholic church, Fairymount, Co. Roscommon.

Detail of St Anne from St Peter and St Anne, with the Lamb of God (1907–8), Sacred Heart Catholic church, Fairymount, Co. Roscommon.